Echoes of 1971: A journey through memories

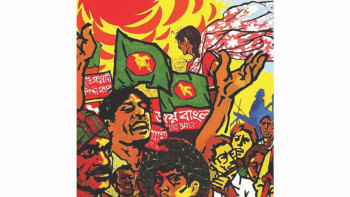

Over the last four decades, commemorative writings about the liberation war have established themselves as a separate genre of writing in the literary scene in Bangladesh. The enormity of the experience of the 1971 war is to some extent found in the memoirs written about this event. Political leaders, intellectuals, victims and survivors, freedom fighters, foreign observers, and military leaders from all three countries - Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan - entwined in the Bangladesh liberation war wrote about the war in the form of memoirs. They wrote to exonerate themselves, to narrate their heroic deeds, or to bear witness and fight for justice in the post-1971 days.

Many events and political developments in Bangladesh following the 1971 war worked as "commemorative thrusts" for authors to write about the event. Commemorative writings about 1971, no doubt, are informed by the writers' political affiliation as well as their location in the political trajectories in the post-1971 decades. Neither are they devoid of the element of reconstruction of experiences as while remembering "we add feelings, beliefs, or even knowledge we obtained after the experience," as said by Daniel L. Schacter. At times their writings align with the institutional or official version of any government or party they belong to. Still, something is fascinating about the popular memory of 1971.

The way the stories are told and narrated - or the specific emplotment style or motifs that enable the narrators to tell their story of the war the way they are, more often than not, transgresses any sanctioned versions of it by any government and political groupings. Being driven by "the urge to tell" the way they tell always spills over the constricts of the official narrative or "official memory." They contain clues for a better understanding of the complexities and the layered nature of this great event. Moreover, naturally – there are class and gender traits in the writings— women's writings differ significantly from men's writing, rank and file's from that of strategists. Nowhere are the memoirs of 1971 more intriguing and anfractuous than those written by women and freedom fighters.

Freedom fighters had to participate in what Tolstoy, in another context, called the "actual killing." Women, on the other hand, in the absence of male family members, had to take care of the family and throughout the war lived under constant threat of sexual violence. In most cases, where husbands were martyred, after the war they had to go through extreme hardship to maintain their families.

The voice of the victims and participants that gains expression in the form of memories is discordant with any dictated narrative. Rather than abiding by the "myth of war" (not in the sense of fabrication but the simplified narrative of the war) which tries to present war as "imaginable and manageable," as observed by Samuel Hynes, these voices tell the everydayness of it and the immensity of the experience in the time of war, that at times get discarded while writing the history of the war.

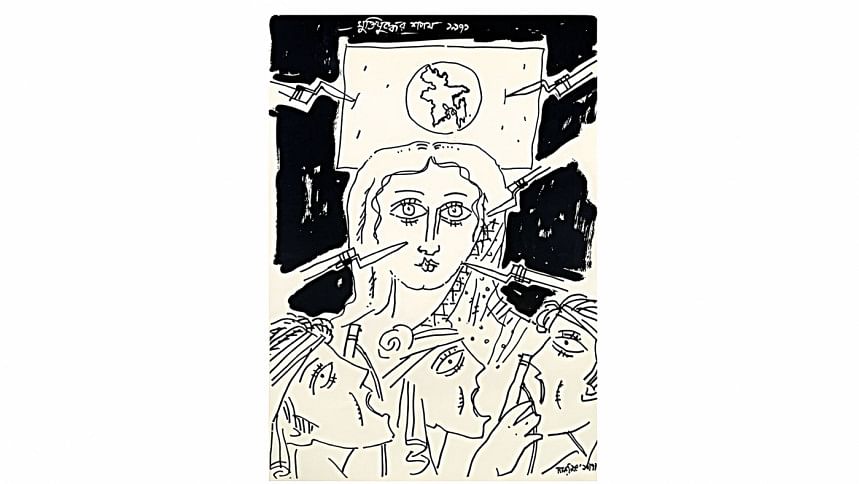

As in the case of any other event, women's experiences found in the popular memories prerequisite a shift in perspective. Remembrance in the present world is closely connected to the family history of victims, as modern war has moved into "every corner of civilian life." Women in particular played a pioneering role in making connections between the family and the nation. From the writings of Jahanara Imam, Basanti Guha Thakurta, and Begum Mushtari Shafi - who lost their family members - we can discern this connection between these two units of society.

Rape, torture, and extreme forms of sexual violence against women were an integral part of the 1971 war. The history of any hostility is replete with incidents of sexual violence. In the subcontinent, it was most visible during the partition of India (most notably in Punjab) and in the Hindu-Muslim riots both before and after partition. However, the sexual violence perpetrated against Bengali women during the Bangladesh liberation war presents a strange juxtaposition of male anxiety, paternalism of the state, figurative representational abstraction, and silence, at times piety.

One example can be cited here. In his renowned book Guerrilla Theke Sammukh Juddhe, Mahbub Alom narrated an incident. Sometime in July 1971, he and his team ambushed a Pakistani military convoy in the Panchagarh region. As part of their preparation, they stayed in a hideout in a village that, like almost any village in 1971, provided them with shelter, food, and valuable information about the movement of the occupying army. After the operation, the Pakistani military, as a retaliatory measure, attacked this sympathetic village, Badlu Para. The village was looted, and subsequently, people were killed. The most devastating news for the Muktijuddhas was the rape of women by the Pakistani army. When the news of the atrocities inflicted upon the women of Badlu Para and its neighborhood reached Mahbub Alam in the camp across the border in Indian territory, he wrote:

"Suddenly, the face of that young, tender, and dusky-faced beauty, seen on that deep night, in the dim glow of a kerosene lamp, emerged. She is Sazim Uddin's wife. Was Sazim Uddin's wife also among the tortured and inflicted upon mothers and sisters of Badlupara? A pang of guilt rises inside me. I feel like a great sinner—all of us."

The way Mahbub Alam talked about the question of sexual violence is telling at the same time it is an example of distancing. This is the narrative style that is found in many memoirs written by men. In voices of the survivors, we find a radically different tone.

In comparison to memories about 1947, which are tinged with an undertone of helplessness, the memories of the 1971 War the narrator's voice comes across as heroic. Where 1947 is unexpected – everything was going fine, it happened all of a sudden. 1971 is rather assured, like the nation-state the narrator foresaw and whenever possible took initiative at the time of despair– an aspect which I called "looming."

For women who were subjected to sexual violence, on the other hand, it was not always the great event that was foreseen. It was like being caught in the storm and being not able to escape. From the writings of Ferdousi Priyavashini and Rama Chowdhury, we see that 1971 was not only heroic but "grave" too. To Ferdousi Priyabhasini, the year 1971 is not merely "Mohan Ekattor" (the glorious 1971), she rather called it "vile and awful, horrible 71" that has taken away all the love from her heart. "1971 had lost all the vestiges of humanity, purity, and conscience." Or as Roma Chowdhury, the rape victim of 1971 wrote, who in the post-1971 days survived on selling her books from door to door, wrote "All my sorrows and miseries stem from the year 71. The burden on my shoulders, empty feet, and the agony of solitude are all contributions of 71... The seeds of these hardships of my life were sown in the year 71."

It is not that their narratives do not cross paths with what by using John Bodnar's term be called "official memory"- they do on the grounds of patriotism. But it is also true their testimonies significantly question the post-1971 society. Ferdousi Priyobhasini wrote that after "crossing the nine-month-long turbulent sea of time," she writes, that the reality she faced in post-independent Bangladesh was no kinder than that of 1971. "Once the glorious liberation war of 1971 ended, while all others had returned home in joy, the society again shackled me on all sides with its cruel chain." Similarly, Roma Chowdhury wrote that the seed that was sown in 1971, today, "those seeds of suffering are yearning to touch the sky with the wings of sorrow."

These memoirs are critical in defining the afterlife of the Ekattor. It is also important to note that the memoirs of 1971 are, in a curious way, intertwined with the history of 1971 – which also implicates the future of 1971 and, for that matter, Bangladesh - the country the war has created. Writers of these memoirs, on the one hand, say they are not writing the history of 1971 - only telling their part of the story; on the other hand, they are assured that without incorporating their perspective, a proper or more holistic or truer history of 1971 could not be written.

Mohammad Afzalur Rahman is currently pursuing PhD at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments