Birangona Women of Bangladesh

I stood beneath the January sun, locking eyes with a Birangona woman on a balcony above me. Her warm smile steadied my trembling heart. Inside, 21 Birangona women awaited us at Sirajganj Uttaran Mohila Sangstha. I was finally here. The year was 2010.

At 17, I first learnt the word Birangona—Brave Woman—from my father, Muhammad Lutfur Rahman. He was a freedom fighter in our bloody Liberation War. He described seeing hundreds of raped women and girls standing back-to-back on a convoy of trucks like sacrificial animals—an image that stayed with me forever.

During the war, the Pakistani Army and their local collaborators carried out a systematic campaign of genocide, rape, and torture against 200,000 to 400,000 women and girls as part of their war strategy. Bengali women were declared gonimoter maal (war booty), openly endorsing their rape.

The Liberation War of Bangladesh stands as one of the earliest documented instances where rape was systematically used as a weapon of war. As Susan Brownmiller observed in Against Our Will, it marked the first time the global community acknowledged that organised sexual violence could be used to terrorise an entire population.

Australian physician Dr Geoffrey Davies came to Bangladesh in 1972 under the UN banner after rising suicide rates among raped women drew global attention. His team performed over 100 abortions a day. In an interview with Dr Bina D'Costa, Dr Davies revealed that General Tikka Khan's orders aimed to weaponise rape during the war. His directive was to impregnate as many Bengali women as possible, ensuring that a "good Muslim" would fight anyone except his father. This brutal strategy turned women's bodies into battlegrounds, leaving a deep and haunting scar on history.

Yet, where did these women go? After the war ended in 1971, the Bangladeshi government granted them honorific titles—an unprecedented act. But in reality, they were hidden and forgotten. Trapped by the stigma of rape and collective shame, they endured isolation and ostracisation in a free society, while the perpetrators remained largely unspoken of.

I am not an academic or journalist—I am a theatre practitioner, writer, and filmmaker. My truth comes from deep observation, from the pain hidden in plain sight—the silent cry that defines my truth.

When I stood before the 21 Birangona women, 39 years of silence separated us. But they welcomed me with open arms and beautiful smiles, offering their prayers and blessings. At that moment, I felt small—like dust. Their love and blessings radically transformed me. I sought their permission to film their accounts. Perhaps I had been searching for them since I was 17, believing there must be many like me who wanted to know them. I felt a deep sense of urgency to document their testimonies.

For decades, we have witnessed the distortion of history, manipulated for political gain, and this practice continues to this day. As part of the first generation of a newly independent nation, I lived through two brutal military coups. History books changed with every new regime, leaving key truths hidden. For example, children of my generation were taught we fought against "perpetrators" in 1971, but who they were was never mentioned—were they aliens?

My father instilled in me an unwavering passion for the Liberation War, sharing its glorious moments like forbidden tales. I am deeply grateful for this, though I struggle to understand how forces opposed to our nation's birth are still influential and effective. Somewhere along the way, we made a grave mistake and are still paying the price.

Listening to the Birangona women, their words shook me to the core. On our way back, Birangona Aasia grabbed my hands, saying, "No one wants to listen; they hate us even more."

After meeting them, I held their precious stories close. I heard that one of the women I met had died. Her name was Bahaton. I did not want to forget her face; her story, like all the women's, was disappearing. I realised that when a Birangona woman dies, her story dies with her—as if their lives never mattered.

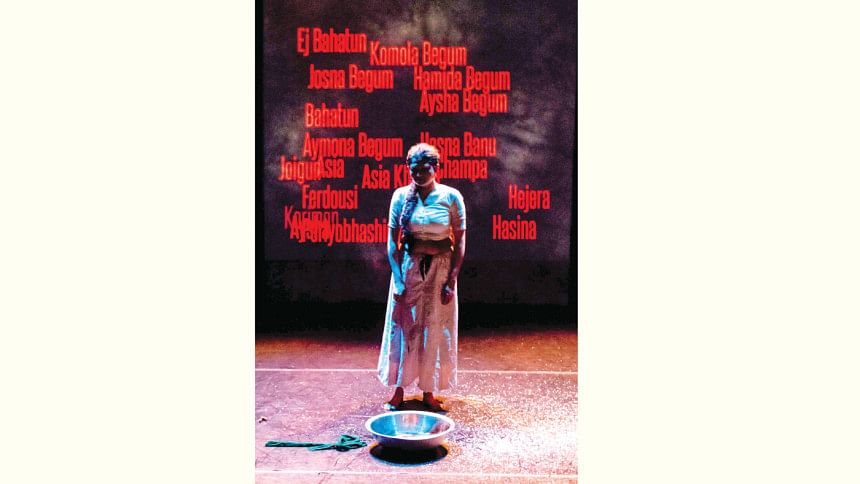

This forced me to return to Bangladesh in 2013 with Komola Collective, to develop the play Birangona: Women of War. During my second visit, I met Rajubala'di, Aasia, Karimon, Joygun, and Surya Apa, and we found peace in their love and care.

As the first performance approached, held at the Liberation War Museum on August 29, I felt a wave of emotion upon seeing them. When I realised the significance of their presence, my entire body froze. Would we be able to tell their stories?

As the play began, I could not avoid looking at the Birangona women in the front row. Their sobs grew louder, and one woman fainted. I was torn—should I stop the performance? I later learnt she had feared that the Pakistani Army had returned. She had to be reassured: "There is no Pakistani Army. We are free now."

We were devastated, questioning whether we had done the right thing. But they wanted to see their own stories on stage. Afterwards, their coldness struck me. They did not even look at me, as if a wall had formed between us. But then, as they prepared to leave, Korimon Apa asked, "Will you perform this play only in London?" When I assured her we would take it to many cities, Raju Bala Didi's words echoed: "Go, tell the world!"

These women have entrusted us with their stories of suffering, courage, torture, and resilience—stories that must be shared with the world. Amplifying their voices will always be my greatest privilege.

In 2014, the Offie-nominated play Birangona: Women of War toured the UK. The Guardian called it "a powerful, groundbreaking production." The play was written by Samina Lutfa and Leesa Gazi, directed by Filiz Ozcan, with music by Sohini Alam and Ahsan Reza Khan, lighting by Nasirul Haque, and research advice from Hasan Arif. We also took the Bengali translation to Bangladesh and staged a special performance at the Central Shaheed Minar—an unforgettable honour.

In Sirajganj, a performance at the Shaheed Monsur Ali Auditorium celebrated the Birangona women, who attended with pride. Birangona Surjya Apa said, "Now we can walk on the streets with our heads held high. No one dares to insult us."

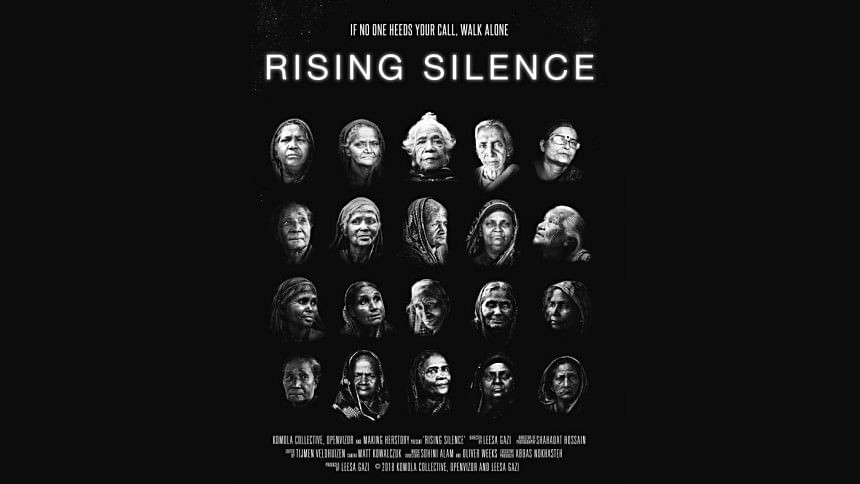

Rising Silence – Research

When I first set out to meet the Birangona women, I could not picture their faces—just a collective entity weighed down by history. But they are not just statistics or labels. Each has a name, a story—they are daughters, mothers, wives, friends. They are any and every woman.

Meeting them changed everything. I see their faces now—I could have been one of them. While researching the film, I travelled across Bangladesh, meeting 83 survivors of mass rape and torture. They welcomed me into their homes and lives without judgement, sharing their stories beyond history and politics.

The nine women in the film come from different backgrounds, ages, religions, and languages, but they share one devastating truth—they are Birangona. Their stories reveal the brutal, indiscriminate nature of sexual violence in conflict.

During my research, one moment shaped the heart of the film. I visited a remote village to meet three sisters who had been held in the same rape camp with 22 other women. As we began talking, Amina Apa, the eldest sister, suddenly asked, "Are you ashamed to sit with us?" Her question cut

deep. I realised how often they had been treated as outcasts, observed from a distance. They did not want to be studied—they wanted connection, understanding, and respect. That moment taught me that the film had to be about intimacy and shared humanity, not just testimony. Their wish became the soul of the documentary.

My Learning

I began this journey to make a film about the extraordinary Birangona women, but their stories ended up transforming me. Their resilience and strength taught me what I am capable of as a woman and gave me a sense of pride and humanity I had never known. We do not truly know our strength, compassion, or power to love until we are tested—they are living proof of that.

Knowing them has made me want to be a better person, to face life with empathy, courage, and dignity. They have shown me that kindness is a practice—the more you give, the kinder you become.

Despite unimaginable suffering, they remain brave, resilient, and loving. How is that possible? The film explores this strength—the spirit to rise above devastation and still hold onto sweetness of heart. They are not only raped women; they embody defiance and dignity. They have risen from the ashes and built a life. They are each a phoenix bird.

I do not know how it is possible to save others while living through such horror—yet they did. They disowned their children to protect them, built futures while haunted by the past, and fearlessly spoke their truth. By living, they have conquered the monsters of war and daily prejudice with extraordinary courage and profound love.

Birangona Rajubala once said, "The one who loves, their heart will weep forever. That's why my tears never end." Then she broke into song and dance. After everything, they still have the heart to celebrate life. "Being human is the best form of existence," Rajubala declares.

Trauma

The trauma the Birangona women carry is relentless. Birangona Jharna Basu Halder once mistook a classmate for her abuser. The shadows of their tormentors haunt them everywhere—that is the grip of PTSD.

In November 2018, we attended a global survivor network in the Netherlands with two survivors. As we approached the hotel, Jabeda Apa froze at the door. "What if someone breaks in and tortures us?" she asked.

Once, Birangona Shurjyo Begum pointed to a hayfield and said, "Look, they are coming. You can't see them, but I can." None have escaped the psychological wounds—they have simply learned to live with them.

Birangona women endure not just physical and emotional trauma but also societal stigma that extends to their children and grandchildren. They seek solace in each other, in prayers and music. They carry an unbearable burden, and without any warning, it can come forth.

Worldwide Impact

Rising Silence features the stories of nine Birangona women—five have passed away, but their blessings drive our mission to spread their voices. Birangona Amina Begum said, "The world now knows our name."

In January 2019, Birangona Rijia Begum and Nurjahan Begum accepted the Best Documentary Award at the Dhaka International Film Festival—a goosebump moment. The film has won 15 international awards, including the 2019 Moondance Winner (USA), and Best Feature Documentary at the PSVI Film Competition by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, UK.

In November 2018, at a symposium in The Hague, Birangona Anwara Begum and Jabeda Khatun joined survivors from 15 countries, calling for a global reparations scheme to address the impact of sexual violence in conflicts. On her first trip outside Bangladesh, Jabeda Khatun addressed a panel of world leaders. She said, "We've been recognised in Bangladesh. Now we want reparations. We want the world to recognise us. What will you do about it?"

In August 2019, Dr Mukwege's Foundation organised a global online screening, bringing the film to viewers in Asia, Europe, the UK, and the US. It has been shown at institutions like the University of Cambridge, LSE, SOAS, and more. Rising Silence was part of the South Asian Feminist Capacity Building Course and featured on BBC's Witness History podcast. The British Psychological Society used it to explore trauma's impact, and 22 students wrote dissertations on its themes of sexual violence in armed conflict.

Rising Silence has been shown around the world to raise awareness and mobilise advocacy campaigns about the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war in current armed conflicts. The film has become a powerful advocacy tool to address the issue and facilitate discussion. The relevance of this documentary is apparent as women continue to bear the brunt of sexual violence in armed conflicts worldwide, from Palestine to Myanmar, Syria to South Sudan.

Birangona women entrusted us with their stories, and we are committed to amplifying their voices, ensuring they are remembered with love and pride across time and borders, inspiring a global call for justice.

"With each day that passes, the Birangona women of Bangladesh are dying out, and with them, their stories: stories which we, as part of an international community striving to end sexual violence in conflict, cannot afford to ignore. Many of the women have passed away, but through Rising Silence, their stories live on," said the Mukwege Foundation. The powerful voices of Bangladeshi Birangona women are inspiring the world to listen, act, and demand justice.

Leesa Gazi is an author, theatre worker, award-winning filmmaker and co-founder of Komola Collective.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments