‘The truths written in blood cannot be erased by lies’

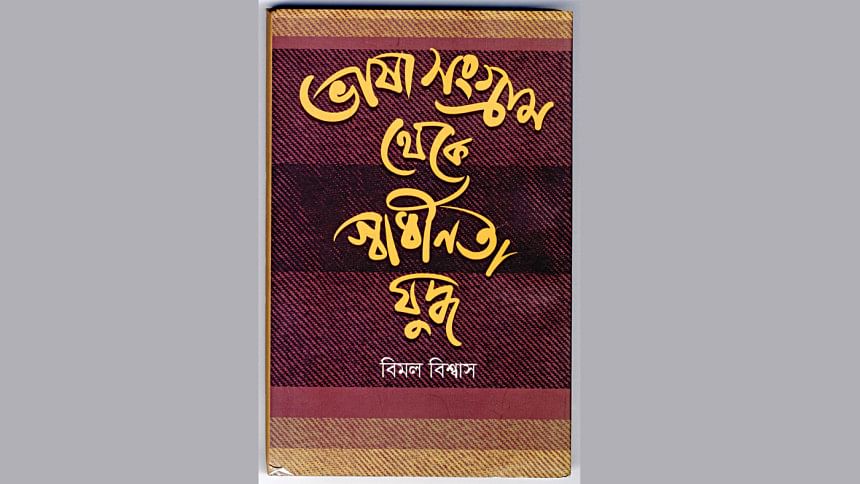

Bimal Biswas—veteran politician and noted writer—played an active role in several battles against the Pakistani junta during the 1971 Liberation War, particularly in the Jessore, Narail, and Khulna regions. In this exclusive interview with The Daily Star, he recounts his wartime experiences and sheds light on the inner workings of his party, the EPCP (M-L).

The Daily Star (TDS): How did events unfold in your locality at the outset of the war?

Bimal Biswas (BB): On 25 March 1971, the Pakistani army launched a brutal attack on the Bengali nation. In response, leaders and activists of the EPCP (M-L) in Narail seized control of the Narail treasury by 11 a.m. on 27 March, aiming to organise an armed national resistance against the onslaught. Of the weapons obtained, 90 percent went to the EPCP (M-L), while the remaining 10 percent were distributed among Awami League and Chhatra League leaders and activists. Similarly, on 28 March, EPCP (M-L) workers seized weapons from the Jessore city treasury.

Since March 1970, I had been in hiding under a false arrest warrant issued by the Pakistan government. At the time, I was a member of the EPCP (M-L). Previously, I was elected general secretary in 1966–67 and vice president in 1967–68 at Jessore Victoria College. During that period, Chhatra Union held an overwhelming majority in the region's educational institutions. On 29 March, a joint force comprising EPR personnel, Awami League leaders and workers, and our party members set out to attack the Jessore Cantonment. At Jhumjhumpur, Biharis attempted to resist them and fired rocket launchers from the cantonment. In the ensuing conflict, many Biharis were killed by enraged Bengali civilians. Thousands of people then marched into Jessore city and advanced toward Jessore Jail. Ultimately, the jail was attacked, and prominent leaders—including Amal Sen, Baidyanath Biswas, Advocate Syed Golam Mostafa, and Gokul Biswas—were freed.

TDS: How did you and your party respond in the days that followed?

BB: On 14 June 1971, the district committee held a meeting where Nur Mohammad presented his written speech. The committee unanimously accepted the document, which emphasised the necessity of a unified Bengali national resistance against the Pakistani forces' armed aggression. It called for a temporary alliance with the Awami League and stressed the importance of avoiding conflicts with the party under any circumstances.

During the meeting, Shamsur Rahman was elected secretary, and Nur Mohammad was co-opted into the district committee. A military commission was formed to lead the war effort, comprising Nur Mohammad, Khabir Uddin, and myself, with Nur Mohammad serving as convener. He was also appointed Political Commissioner and Army Chief. Later, at a district committee meeting held at Badshah's house in Ghoshgati from 20 to 24 August, I was assigned the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Force.

On 1 September, a decision was made to establish a regular army. Following the formation of a free zone, it was further decided to set up a revolutionary committee in the Pulum region. However, during discussions, Sudhanshu Roy referenced Mao Zedong's Selected Military Writings and posed a question to Nur Mohammad and me: did our base area meet the five conditions Mao outlined for establishing a free zone?

Mao Zedong's five conditions were:

a. A strong party;

b. A strong military force;

c. A strong mass base;

d. The ability to address public crises arising from the ruling government's economic blockade;

e. A secure rear ground to protect the party and troops from enemy attacks.

To be honest, the reality was that we were in dire straits in the war.

TDS: What are some of the most significant experiences you had during the Liberation War?

BB: Guerrillas captured the Shalikha base, with the final attack taking place on 4 September 1971. Prior to this, the Shalikha Razakar camp had been attacked twice in succession, leading to the capture of the thana as the Razakars fled. However, in the 4 September attack—which I strongly opposed on tactical grounds—we suffered great losses. Abul Bashar, a brilliant student from Harishpur, was martyred. Imran (Anis) of Narail also lost his life; his grave still stands on the western bank of the river near Pulum School. Bishwanath Ghosh (Raju) of Khajura and several others were also martyred in the attack.

That night, I left Narail with Saif Hafizur Rahman Khokon to attack the Fazarkhali Razakar camp. However, due to continuous heavy rain and darkness, we were unable to proceed and took shelter at the home of Mizanur's relative in Singia village. Early the next morning, I received a letter from Nur Mohammad, words I still cannot forget:

"Anis, Bashar killed. Bhatt injured. Murad, Raju missing. There is great frustration among the party forces and the people throughout the region. Come here quickly, wherever you are."

On 12 October 1971, Pakistani forces and the Razakars launched an attack from the west.

During that period, Nur Mohammad and I repeatedly emphasised that this regional resistance would not be the final defence. Instead, we urged a strategy of self-defence by disbanding forces to avoid complete annihilation. But no one agreed. Finally, on 31 October, the Mukti Bahini launched an attack on the Jamrildanga road and from Bishnupur in the morning, capturing a large part of Satbaria village.

Knowing that they would leave the area that night, a faction within the party conspired to have Nur Mohammad and me killed. As part of their plan, our gunboats were removed. When I could not find the boat, I rushed to Harekeshtapur village in Mohammadpur, shouting for Kadar Bhai. He responded from the middle of the beel, and I urged him to bring the boat quickly.

Naturally, a question arises: why did the Mukti Bahini, at some point, start attacking us—even though we had fought against the Pakistani forces? The answer is simple. Neither our party nor we had any affiliation with the government-in-exile. These events unfolded as part of an effort to seize control of our territory.

Additionally, while returning from Pulum, 48 people were arrested, and 32 of them were executed by the Razakars—most of them from Kaliganj Upazila. Among them were Phulu Joardar, Gaffar Biswas, Golam Rahman, and Motaleb Hossain. The remaining 16 were released after enduring endless torture, but many of them died within five to seven years due to their injuries. Near Arpara Bridge, Razakars killed another 12 people who had been returning from Pulum.

Despite the sacrifices of hundreds of comrades in Jhenaidah, Jessore, Narail, and Magura in our battle against the Pakistani forces, certain factions within the Awami League and the left sought to deny our struggle. However, the brutal truth of history is that truths written in blood cannot be erased by lies.

TDS: How would you describe the differences between your party and the Awami League during the war?

BB: The heroic struggle and sacrifices of the EPCP-ML leaders and workers in the greater Jessore district against the Pakistani Army were driven by the vision of creating a non-communal, democratic, and exploitation-free Bangladesh. The Jessore district committee never accepted the dui kukurer lorai (fight between two dogs) theory, which was promoted by then-EPCP-ML leader, Abdul Haque. However, when Haque Saheb arrived in the district in August during the siege, I led a seven-man suicide squad to ensure his safe passage to the house of Advocate Mia Mohan in Bowlmari, Faridpur district. There was little hope we would survive the mission, but through strategic manoeuvres, I managed to return to Pulum alive.

To the best of my knowledge, no member of the Mukti Bahini was ever killed by EPCP-ML forces. The training of Mujib's forces was aimed at reclaiming all areas under leftist control, even if it required eliminating their presence. This was evident in past events. Unfortunately, it was the EPCP-ML that suffered the most from the unintended clashes that arose. Before 24 August, the Mukti Bahini or Mujib Bahini had no operational presence in those regions. However, I was aware that most people in the area supported the government-in-exile. Before we left for India on 3 November, it was decided to leave our weapons at Dighirpar village.

TDS: How did things unfold after that phase of the war?

BB: In June 1972, Abdul Haque's theory of "Social Colonisation of East Pakistan by Soviet Social Imperialism" was formally adopted. At that meeting, Anishur Rahman Mallik and I objected, arguing that the term "East Pakistan" should not be included in the party's name. However, the Khulna district committee, led by Khairuzzaman, endorsed Abdul Haque's stance, which led to his visit to Khulna in July. There, the entire district committee, including Azizur Rahman, accepted the theory of "East Pakistan as a social colony of Soviet social imperialism." To my knowledge, only Ranjit Chatterjee refused to accept this theory.

Although we adhered to communist internationalism, we actively participated in the 1971 war because we recognised that Bangladesh's language-based nationalism was a more progressive idea than Pakistan's religion-based statehood. In the greater Jessore district, around 2,000 leaders, members, and supporters of our party were killed by the Pakistani army and its allies during the war.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments