Reading his diaries and understanding the man

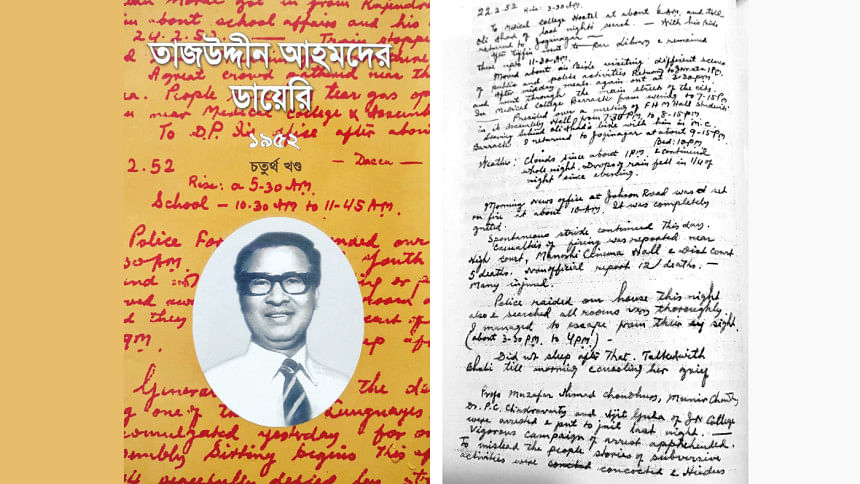

I do not remember who gave me the book—it may have been a friend, colleague, or a student of mine. But once I looked at the title, I was quite intrigued, for the simple reason that the book is a compilation of diaries from 1947 to 1952 by none other than Tajuddin Ahmad, one of the architects of Bangladesh as well as the country's first Prime Minister. So, I eagerly took the book.

As I started to read it, aside from its contents, five things struck me. First, Tajuddin Ahmad wrote something in his diary each and every day for five long years. The tenacity of the man is enviable. Second, it is also a reflection of a disciplined mind. He trained himself to make an entry every day, irrespective of how insignificant the happenings of the day were. Third, the entries were exceptionally detailed in terms of names of people, places, and events. Tajuddin Ahmad took note of every detail, however minute. It may be that he was keen to reflect facts rather than fiction.

Fourth, the language of the diaries is so simple that it feels as though someone is just sitting next to you and speaking. Fifth, the entries are in English, not in Bangla.

In my reading of different books based on diaries, I have come across two basic trends: one, some diaries simply record the facts—what happened, when it happened, and how it happened. To my taste, these sorts of diaries are boring, and I can hardly relate to what is written. Two, some diaries contain stories, observations, inner thoughts, etc. I am drawn to this second type of writing. Needless to say, the diaries of Tajuddin Ahmad belong to the first category.

Thus, as I began reading them, the descriptions initially felt too mechanical, quite dry, and somewhat boring. But soon, I became completely immersed in the writing. It became clear to me that the entries were not merely descriptions of events—they also portrayed the time, the society, and the politics of that era. More importantly, the diaries are a testimony to the evolution of a great leader: his thoughts and ideas, his journey to becoming who he was.

From the diaries, I gathered how deeply Tajuddin Ahmad loved the land of his birth and its people. In various entries, his concerns come through very clearly—sometimes for local areas, like Kapasia, his birthplace; sometimes for Old Dhaka, the centre of his political activities; and sometimes for the country as a whole.

His writing reveals that he was determined to establish people's rights, their voices and autonomy, and their emancipation. He dreamed of a welfare state for the people. On these issues, Tajuddin Ahmad was uncompromising. Some of the patriotic ideals he formed at a young age later shaped his stance on various economic issues when he served as Bangladesh's Minister of Finance.

As evidenced in the diaries, Tajuddin Ahmad was a political animal—politics was in his DNA. Apart from a few personal events, most of the entries are about meetings with friends and peers, who, like him, were deeply involved in political activity. Tajuddin Ahmad was grounded in local realities. He was closely connected with political workers at the grassroots level.

There is an entry in which he describes a meeting with a student activist who had travelled from afar. He spent four hours with him one-on-one. His comment on that meeting was: "It enriched me so much." Tajuddin Ahmad saw politics not as a means to power but as a tool for serving the people. From that perspective, he was absolutely objective and unemotional in political matters. This becomes evident in his conversations with his political colleagues in Old Dhaka.

As a politician, Tajuddin Ahmad was neither a man of empty words nor a drawing-room politician—he was a political activist. From his diary entries, it is clear how, during the Language Movement, he strategised the resistance against the administration, how he mobilised his peers, and how he himself took to the streets.

He stood with the people, as he had throughout his life. He saw the Language Movement not only as a struggle for the cultural identity of Bengalis but also as a broader fight for autonomy and emancipation. This critical phase helped shape his path towards the Liberation War of Bangladesh.

In reading the diaries, I also sought to answer the perennial question: Was Tajuddin Ahmad a socialist?—a label often attached to him, rightly or wrongly. From my reading, it seemed that he was, at his core, a nationalist leader with a strong commitment to social justice, human welfare, equity, and equality.

Was he a Marxist? In strict definitional terms, my answer would be "no", but in spirit, "yes". As he himself once said: "I am neither a Marxist nor a Communist, but I definitely follow the teachings of Marxism in my way of life." He may not have been a Marxist, but he was undoubtedly a socialist, and his socialist ideas were reflected in the economic policies, strategies, and plans that Bangladesh pursued when he served as the country's first Finance Minister.

Reading the diaries, I got a clear sense that Tajuddin Ahmad followed history closely. It also reminded me of his own words:

"You work in such a way that you make history, but you are not to be found anywhere in it."

Selim Jahan is former director of the Human Development Report Office under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and lead author of the Human Development Report.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments