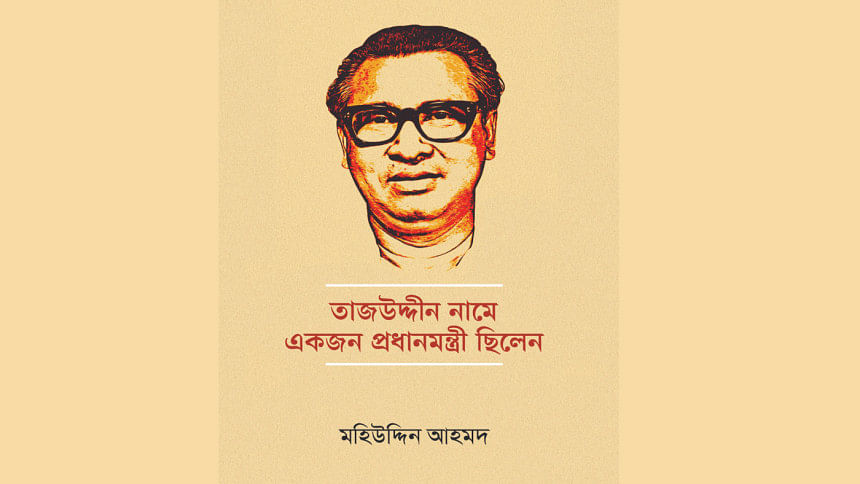

‘Tajuddin’s place in history should be seen in terms of his wartime leadership’

The Daily Star (TDS): How do you view Tajuddin Ahmad's early political journey and his emergence as a key national figure?

Mohiuddin Ahmad (MA): Tajuddin Ahmad's emergence as a key leader of the Awami League was marked by his appointment as General Secretary in 1966. He was later arrested, and while the 1969 mass movement unfolded, he remained in jail; at that time, Amena Begum served as acting General Secretary. After his release, Tajuddin returned to active politics, and from 1970 onwards, his role within the party grew steadily more prominent. However, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remained the party's central figure. His popularity and charismatic presence were so overwhelming that no other Awami League leader was nearly as visible. As is often the case in our political parties, there was essentially only one dominant leader.

In the early years, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani served as party president, but once Sheikh Mujib became General Secretary, he effectively took control of the organisation. It was within this framework that Tajuddin began to rise, though he continued to be overshadowed by Sheikh Mujib.

A sense of humanity and principled commitment was evident in Tajuddin from the very beginning. From the outset, he held strong secular beliefs. Among the young Muslim League activists who later rallied under the Awami League banner, many were followers of Abul Hashim, and Tajuddin was part of that progressive stream.

It is also widely acknowledged that communist ideas had a notable influence on Tajuddin. As he became more active in the Awami League, he distinguished himself from many senior leaders who increasingly aligned themselves with Sheikh Mujib. Yet, since Sheikh Mujib was the undisputed central leader of the party, there was no real tradition of collective leadership. Loyalty to him was essential for survival within the organisation. While Tajuddin was unquestionably loyal, he also maintained an independent outlook—a rare quality in the political culture of the time.

TDS: What challenges did he encounter during the 1971 Liberation War, both from internal party conflicts and external pressures that intensified the crisis?

MA: On 1 March 1971, when the National Assembly session scheduled to be held in Dhaka was suddenly postponed, it was actually Tajuddin who first played a significant role. The idea that there should be a separate constituent assembly and a separate constitution for East Pakistan initially came from him. Sheikh Mujib later adopted this idea, and accordingly, the Awami League prepared a draft constitution. However, Yahya Khan did not accept it.

After that, the West Pakistani crackdown began. Sheikh Mujib never instructed anyone to go to India and form a government. Had he done so, there would have been some form of evidence—but there is none. What he did do was give a few people an address in Kolkata—Chittaranjan Sutar, an operative of the Indian intelligence agency R&AW—and told them to keep the address with them. After 25 March 1971, many people went to that address. But Tajuddin did not go there. Instead, he went directly—along with Barrister Amirul Islam—and they were taken to the Director General of the BSF, who was then Rustomji.

On 3 April, they had their first meeting with Indira Gandhi. It was on Indira Gandhi's advice that Tajuddin formed a government-in-exile. Since he was seeking India's cooperation, a formal government was necessary. Pakistan was a full member state of the United Nations. Bangladesh, still officially a part of Pakistan, could not receive formal support from India unless there was a legitimate government to recognise. Without that, it would not fall within accepted international diplomatic norms.

There was a notable point here: since India did not immediately recognise the Bangladesh government-in-exile, Tajuddin Ahmad himself did not publicly comment on the matter—but he did send multiple letters regarding it.

We have come across information from Dr Kamal Siddiqui, who served as the Private Secretary to Khandaker Mushtaq Ahmad, the Foreign Minister of the Mujibnagar Government. Before taking on that role, Siddiqui had been the SDO (Sub-Divisional Officer) of Narail.

On one occasion, Kamal Siddiqui asked Tajuddin why India had not yet recognised Bangladesh. In response, Tajuddin explained that Indira Gandhi was under considerable pressure. Recognition at that point was risky, as Sheikh Mujib was still in Pakistan. If Sheikh Mujib were to reach some sort of compromise or settlement with Pakistan, India could find itself in a diplomatically awkward position after having already extended recognition.

I have included this account in my book 1971: Kolkata Kondol. We know that in Nigeria, a province called Biafra once declared independence in 1967, and a few countries—especially France—granted it recognition. However, Biafra ultimately failed to achieve independence and remained a part of Nigeria. France later faced serious difficulties because of its support. When a permanent member of the United Nations appears to encourage the disintegration of a member state by recognising a breakaway region, it becomes a serious diplomatic issue.

One of the many reasons behind India's delay in recognising Bangladesh was precisely this: Indira Gandhi did not want to take that risk, especially since no one knew what was on Sheikh Mujib's mind at that time. Later, when Sheikh Mujib was taken to prison in Pakistan and put on trial, we still do not fully know what he actually said during those proceedings. But one thing is clear to us: forming a government and leading the Liberation War from exile was not an option Sheikh Mujib ever considered. There is no evidence to suggest that he contemplated this path.

In addition, it is clear that even within the Awami League, Tajuddin's position was not without contest from some senior leaders. Moreover, many of the military commanders did not like him, and he did not have much control over them either. It was not until the end of July that a meeting was finally held with the sector commanders of the Liberation War. In that meeting, the country was divided into eleven sectors. This reorganisation took place only at the end of July—it had not been possible before that.

According to protocol and the warrant of precedence within the Awami League, Tajuddin Ahmad held a relatively low position. First came Sheikh Mujib, followed by the three vice-presidents—Nazrul Islam, Mansur Ali, and Abu Hena. Then came the Secretary of the All Pakistan Awami League, and only after that was Tajuddin's position considered. So when he formed a government and appointed himself as Prime Minister, many did not take it well—because he had not consulted anyone in making that decision. Since it was a unilateral decision, it was not well received by others.

Leaders of the BLF (Bangladesh Liberation Force) have claimed that Sheikh Mujib had instructed them—and that the Awami League high command also knew—that in his absence, a Revolutionary Council would be formed, which would take the necessary decisions. But Sheikh Mujib had never said that a formal government should be formed in his absence. Tajuddin took a great risk. He acted out of historical necessity—without such an initiative, it would not have been possible to liberate Bangladesh.

The Liberation War had, in fact, already begun on the night of 25 March. The armed resistance started that very night around 10:30 or 11:00 p.m.—with BDR, EPR, and the Rajarbagh police lines actively resisting. So the resistance was already underway; rebellions and resistance were occurring in various places. To lead this movement, a formal government was needed—and Tajuddin understood this before anyone else. Others did not yet grasp this urgency.

Now, one may ask why he did not consult everyone and arrive at a collective decision. But the truth is, in Sheikh Mujib's absence, the Awami League leadership lacked the capacity for decisive collective action. Therefore, Tajuddin made this decision on his own. And I would say that, in one sense, this reflects his firmness and political courage.

TDS: How do you assess the performance of the government-in-exile under the leadership of Tajuddin Ahmad?

MA: I would argue that Tajuddin Ahmad did not really have the freedom to run his administration independently. He was entirely dependent on India—particularly on Indian intelligence agencies. In Kolkata, a Joint Secretary and a Deputy Secretary from India's Ministry of External Affairs were primarily responsible for maintaining liaison with and guiding the Bangladesh government on behalf of the Indian central government.

Tajuddin could not go beyond the boundaries of India's grand design. Many had hoped that Tajuddin would emerge as the global diplomatic face of the resistance—building international public opinion and securing diplomatic support. Historically, we have seen leaders of resistance movements travel the world during such times, like Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, Yasser Arafat of Palestine, and others, who campaigned for their causes internationally. But Tajuddin Ahmad had no such opportunity.

In fact, not just Tajuddin—no minister of the Bangladesh government-in-exile was allowed to set foot outside India, not even for a single day. They were confined to Kolkata and Delhi. At one point, they held a three-day meeting in Siliguri—but even that was arranged by the Indian military.

In short, it can be said that the government operated under a range of limitations and was heavily dependent on India throughout that critical period.

TDS: What happened to him after the Liberation War, and how will history ultimately judge his position?

MA: After the Liberation War, Tajuddin Ahmad essentially began a new chapter in his life. At that time, Bangladesh was going through a deep crisis—rising prices, food shortages, and overall economic instability. As Finance Minister, he was tasked with managing an economy in shambles, and that required bold, visionary national leadership. In this regard, Sheikh Mujib's government lacked the necessary capacity. The situation kept deteriorating, and as Finance Minister, Tajuddin Ahmad increasingly had to shoulder the blame.

Though he did criticise certain issues in various forums, there was a certain timid mood about him—I would say he failed to demonstrate the courage that was required. He never openly spoke out about the widespread administrative mismanagement, lack of cooperation from various ministries, and other systemic issues. He kept presenting national budgets—one after another—in 1972, 1973, and 1974. He could not present one in 1975.

Throughout, he never took the bold step of resigning. Eventually, he was sent a written resignation letter to sign—and only then did he sign it. So, in essence, it can be said that he was made to resign. The humiliation of being dismissed in this way was something he had to endure.

But he alone was not to blame for this outcome. At a certain point, when it was clear that he either could not perform his duties or was not being allowed to, he should have taken the moral and political decision to resign.

But the overall assessment is this—Tajuddin Ahmad, the man—his place in history should be seen in terms of the leadership he provided during Bangladesh's Liberation War. Even though the Proclamation of Independence—which functioned as a provisional constitution at one point—envisioned a presidential form of government, with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the head of state and, in his absence, Syed Nazrul Islam assuming that role, it was ultimately Tajuddin Ahmad's leadership, personality, and administrative approach that defined the functioning of the Mujibnagar Government.

He became widely recognised as the de facto head of the government-in-exile. So, in that sense, when we speak of Bangladesh's Liberation War, his place in history must be determined by the fact that he was the central figure of the government that led the war effort. His legacy rests on being the principal leader of the wartime administration that carried the struggle for independence forward.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments