The forgotten luminary of Bangladesh’s liberation war

History has a cruel way of dimming the light of those who served with quiet dignity while amplifying the voices of those who demanded attention. In the pantheon of Bangladesh's founding fathers, few figures have been as systematically overlooked—and arguably mistreated—as Tajuddin Ahmed, the nation's first Prime Minister. Born on July 23, 1925, Ahmed's story is one of unwavering principle, strategic brilliance, and ultimate sacrifice, yet it remains largely ignored in the popular consciousness of the very nation he helped birth.

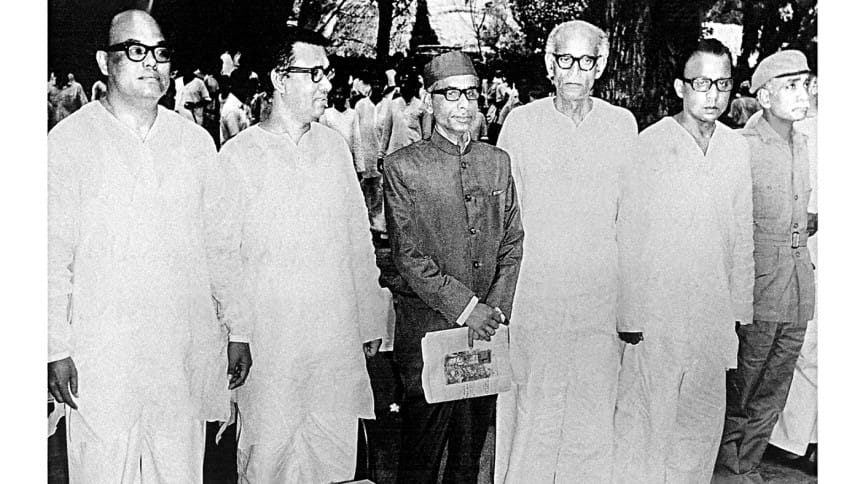

The Hero of 1971

While Sheikh Mujibur Rahman rightfully earned the title "Bangabandhu" (Friend of Bengal), Tajuddin Ahmed led the first Government of Bangladesh as its Prime Minister during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, and is regarded as one of the most instrumental figures in the birth of Bangladesh. When the Pakistani military launched Operation Searchlight on 25 March 1971, it was Ahmad who demonstrated the presence of mind and organisational acumen that would prove crucial to the independence struggle.

In the chaos following the crackdown, while many leaders fled or were captured, Ahmad managed to escape to India and immediately set about the monumental task of establishing a government-in-exile. He became the Prime Minister of the Bangladesh government in exile at Mujibnagar and organised the war of liberation. The Mujibnagar Government, proclaimed on 17 April 1971, was not merely a symbolic gesture—it was a functioning administration that coordinated the liberation war, managed international diplomacy, and laid the groundwork for the independent state that would emerge nine months later.

Ahmad's leadership during this critical period was characterised by pragmatism and strategic thinking. He understood that military action alone would not suffice; the independence movement needed legitimacy, organisation, and international support. Under his guidance, the provisional government established diplomatic relations, organised the Mukti Bahini (liberation forces), and created the administrative framework that would transition into the independent state's governance structure.

The Principled Politician

What distinguished Ahmad from many of his contemporaries was his unwavering commitment to democratic principles and constitutional governance. Unlike the populist politics that often characterised South Asian leadership, Ahmad believed in institutional integrity and the rule of law. This principled approach, while admirable, would later contribute to his political marginalisation.

Tajuddin's life was a long, ceaseless commitment to principles. Even after independence, when opportunities for personal enrichment and political manoeuvring abounded, Ahmad remained steadfast in his convictions. He believed in a parliamentary system of government, fiscal responsibility, and inclusive economic development—positions that sometimes put him at odds with the more populist tendencies of the time.

His vision for Bangladesh was that of a secular, democratic state with a mixed economy that could provide opportunities for all citizens. This vision, though prescient, was perhaps too sophisticated for a nation emerging from the trauma of war and struggling with immediate survival needs.

The Tragic Downfall

The greatest tragedy of Ahmad's story is not merely his assassination but the circumstances that led to his political eclipse. He resigned from the cabinet in 1974 to live a quiet life. This resignation was not born of personal ambition or political manoeuvring but of principled disagreement with the direction the country was taking.

Ahmad had grown increasingly concerned about the concentration of power, the suspension of democratic institutions, and the establishment of a one-party state. His opposition to these developments, while constitutionally sound, marked him as a potential threat to the new order. In late July 1975, he received a desperate call from a trusted source, warning him of a conspiracy to assassinate Bangabandhu. True to his loyal nature, he rushed to warn Sheikh Mujib, despite their political differences.

The assassination of Bangabandhu on 15 August 1975 sealed Ahmed's fate. Following Sheikh Mujib's assassination in a coup d'état, Tajuddin was arrested and assassinated on 3 November 1975 while in prison, along with three senior Awami League leaders. On 3 November 1975, just over two months after their capture, all four men were brutally assassinated—a flagrant violation of both prison regulations and the nation's legal framework.

This heinous act completed a systematic campaign to eliminate every key leader from the 1971 government. Only one figure from that era's leadership survived: Khondoker Mushtaque Ahmed, Tajuddin's former colleague in the government-in-exile, who had conspired with pro-Pakistani forces to orchestrate this carnage. Even during the 1971 struggle, Mushtaque's loyalty had been questionable, though Tajuddin had managed to contain his subversive influence and prevent him from undermining the independence cause. The 1975 assassinations represented the ultimate settling of scores—revenge finally seizing its moment.

The manner of his death was particularly barbaric. The four senior leaders of the Awami League were killed with "bullets and bayonets" by those opposed to Bangladesh's liberation, working closely with Bangabandhu's assassins. As he went down the stairway of his residence in August 1975, a man in army custody, Tajuddin told his wife he might be going away forever. These words proved prophetic, and his widow was left to raise their children alone, struggling against both poverty and the political ostracism that followed.

Historical Injustice and the Need for Rectification

The treatment of Tajuddin Ahmad's legacy represents one of the most glaring injustices in Bangladesh's historical narrative. While other leaders have been celebrated with monuments, institutions, and extensive biographical works, Ahmad has remained largely in the shadows. This oversight is not merely academic—it represents a fundamental misrepresentation of the independence struggle and the values upon which the nation was founded.

Several factors contributed to the historical marginalisation of Tajuddin Ahmad. First, his principled opposition to authoritarian tendencies made him inconvenient for successive governments that preferred compliant historical narratives. Second, his intellectual approach to politics and governance lacked the populist appeal that resonates with mass political movements. Third, Tajuddin's assassination removed his voice from post-independence political discourse, leaving his legacy in the hands of others with different priorities.

Moreover, the political dynamics of post-independence Bangladesh meant that acknowledging Ahmad's contributions might have implied criticism of other leaders' actions. This created a climate where his role was systematically minimised.

The Case for Restoration

The time has come for Bangladesh to rectify this historical injustice and properly acknowledge Tajuddin Ahmad's contributions. This is not merely about historical accuracy—though that alone would justify the effort—but about reclaiming the values and vision that he represented.

Ahmad's commitment to democratic governance, constitutional propriety, and inclusive development remains relevant to contemporary Bangladesh. His understanding that independence was not merely about political sovereignty but about creating institutions that serve the people offers valuable lessons for current challenges.

The resurrection of Ahmad's legacy should involve several concrete steps. Educational curricula should properly reflect his role in the independence struggle and post-liberation governance. Public institutions should bear his name, and scholarship programmes should support research into his contributions. Most importantly, his political philosophy and approach to governance should be studied and discussed as part of the ongoing effort to strengthen Bangladesh's democratic institutions.

Conclusion

Tajuddin Ahmad was more than Bangladesh's first Prime Minister—he was the architect of its independence struggle and a visionary leader whose principled approach to governance offers enduring lessons. His assassination was not merely the loss of a political leader but the silencing of a voice that advocated for the democratic values and institutional integrity that any nation needs to thrive.

The failure to properly honour his memory represents not just ingratitude toward a founding father but a fundamental misunderstanding of the values that should guide the nation he helped create. Bangladesh's journey towards fulfilling its founding promise remains incomplete as long as leaders like Tajuddin Ahmad are kept in the shadows.

Tajuddin was merely 50 years old when he was murdered, leaving behind a young family and an unfinished vision for his country. The ultimate tribute to his memory would be the creation of the democratic, just, and prosperous Bangladesh he envisioned—a goal that requires first acknowledging the debt the nation owes to this forgotten architect of independence.

In remembering Tajuddin Ahmad, we remember not just a man but a set of principles that transcend individual personalities and political calculations. His resurrection in the national consciousness is not about partisan politics but about reclaiming the values of integrity, service, and democratic governance that he embodied. Bangladesh deserves to know and honour this remarkable leader who gave everything for his country and asked for nothing in return.

The prevailing impulse to diminish our heritage of struggle and liberation while undermining the legacy of our founding fathers portends troubling times for our nation. The ramifications manifest themselves with stark clarity: diminished leaders stumble through obscurity, stripped of wisdom and bereft of any sense of national purpose, while our directionless state founders amid tempestuous waters. What we urgently require is another sagacious and prescient leader of Tajuddin Ahmed's stature—one capable of delivering us from our own folly.

K A S Murshid, an economist, served with the Foreign Ministry of the Mujibnagar Government during the Liberation War in 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments