How best to remember our martyred intellectuals

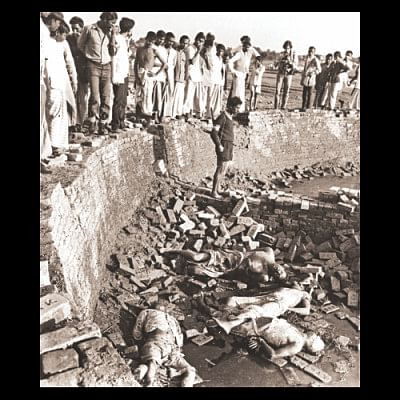

Every year on December 14, we remember our martyred intellectuals who lost their lives in 1971 at the hands of Pakistani death squads comprising military men and their local abettors. They were picked up from their homes at night, blindfolded, tortured, and shot or hacked to death. Their bodies were thrown into ditches or shallow graves to be devoured by jackals and vultures. Many of those martyrs remain traceless even today, and their families, after enduring excruciatingly long waits for their return or the news of the recovery of their remains have given up hope of ever seeing them again. They find some consolation in the fact that they have carved out an everlasting place in the collective memory of a grateful nation.

The killing of the intellectuals began on the night of March 25, 1971 and continued throughout the year. In the final days leading up to their defeat and surrender, the Pakistanis, in a final act of desperation went on a killing spree. Some estimates put the number of martyred intellectuals at around 200, while recent genocide studies have found the number to be much higher, since the deaths of many teachers, lawyers and physicians from the district and sub-district towns still remain outside of the official reckoning.

If the March 25 killing of the intellectuals (Dhaka University teachers and students being the initial targets) reveal a well thought out and coordinated plan of the Pakistanis to systematically destroy the nation's intellectual capital, the December 14 massacre only shows how anguished they felt for not having finished their agenda. The Pakistani military in general and its intelligence wing in particular, were well aware of the power of our intelligentsia to influence public opinion and inspire the people to resist Pakistan's colonial rulers. They were convinced that the intelligentsia, committed to Bengali nationalism and ideals of socialism, social justice and secularism, were the main threats to their authoritarian and exploitative rule. The fundamentalist religious parties of Pakistan led by Jamaat-i-Islami, in their zeal to eliminate all left leaning and secular forces in the country – whom they branded 'anti-Islamic' -- joined hands with the army. In 1971, this unholy alliance took a sinister form. With the formation of Razakar, Al-Badr and Al-Shams outfits, it became much easier for the Pakistanis to carry out their plan.

It would however, be wrong to assume that the killing of the intellectuals was a uniquely Pakistani operation without any historical precedence. Indeed, if we look at the way the Pakistani military rewrote what Lord Byron called 'The Devil's Scripture' and carried out the murders, it would seem that it had simply taken a page out of the Nazi history of intelligenzaktion or the killing of intellectuals. During the Nazi occupation of Poland as many as 61,000 teachers, priests, physicians and writers were killed. Their dead bodies were dumped into mass graves, many of which haven't yet been identified. The Nazis carried out the secret murders to stifle the protesting voice (which a Polish poet of the Kolumbs, or Columbus – generation, Miron Bialoszewski described as the 'loud voice of conscience') and any resistance against their occupation of Poland. During 1971, Major General Rao Forman Ali who was in charge of the military police and auxiliary forces operating in occupied Bangladesh compiled a list of prominent Bengali intellectuals and wrote down their brief biographies in a diary. The execution of most of those whose names he had listed only shows how meticulous and savage the Pakistani military was. The Nazis too had prepared a list before World War II, known as the Special Prosecution Book, which also listed key biographical facts about the victims. General Rao Forman Ali was probably inspired by the Nazi formula, because as a crafty and cool operator, he needed a clue or two from smarter operators before him to effectively carry out his plan.

Intellectuals in all ages, especially those who dare to 'speak truth to power' – to borrow a phrase from Edward Said – and guide the people in their struggle for freedom, have found themselves in the prosecution books of the rulers. Each of the martyred intellectuals of 1971 had spoken to power in their own way on issues that the Pakistani rulers were not willing to address, let alone compromise. They had done so in their role as writers, educators, journalists, lawyers or physicians at a time when both people and politicians looked up to them to provide intellectual leadership. Ever since the 1952 language movement had forged all the citizens into a political force with a strong will to power, the professional engagement of the intellectuals expanded beyond their immediate circles of colleagues, students, clients or patients to reach a wider audience. As educators they taught their students the basic coordinates of an enlightened existence – one that is devoted to the good of the others – and inspired them to rise above the average -- average action, average opinion, and average expectation. (This is what Professor G.C. Dev, the noted philosopher and philosophy professor and Dr. Jyotirmoy Guhthakurta, a teacher of the English department of Dhaka University, two of the martyred intellectuals I have had the privilege to be close to, did in the most unassuming ways). As lawyers, they were instrumental in shaping our expectations about justice, particularly social justice, and our rejection of the colonial legal apparatus of Pakistan. As writers they guided their readers in their search for cultural, intellectual and aesthetics roots and taught them how to harness their strength for social change. And as physicians they earned enough trust of their patients so that when they alerted them of our ongoing struggle for freedom, they renewed their pledge to be a part of that struggle. Many patients of Dr. Alim Chowdhury, the martyred ophthalmologist, spoke of the brief but meaningful conversations they had with him in 1971 that led some of them to enroll in the Mukti Bahini – the liberation fighters.

This brings us to the larger and more nuanced issue of the role of intellectuals – public intellectuals to be more precise – in times of crisis. If the killing of the intellectuals in 1971 proves one thing --it is their ability, to use a phrase from Lionel Trilling, to unite 'the activity of politics with the imagination under the aspect of the mind.' And, in a country like Bangladesh where politics is pervasive (I am reminded of a couple of lines someone quoted at the head of an essay on Marx without naming the source: 'Everything is political, and the choice to be “apolitical" is usually just an endorsement of the status quo and the unexamined life' which perfectly sums up the way we view politics) the silence of the intellectuals on issues affecting the people leads to an erosion of their rights. Intellectuals, indeed, have very little option when it comes to choosing between a private and a public role. The way the people regard them tells them of the need of a national engagement. They are expected to bring the world of ideas and the world of politics together for ensuring equity ad social justice. Throughout the 1950s and 60s many intellectuals played their public roles with dedication and commitment. Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks has divided intellectuals into two groups –traditional and organic. Traditional intellectuals are teachers, administrators and priests whose professional activities remain the same over generations while the organic intellectuals lend their special abilities to classes or enterprises to organize their interests. They are the active ones, helping change minds and, for special interest groups, extend the market reach. Edward W. Said, in his 1993 Lectures (later published as Representations of the Intellectual, 1994) said that according to Gramsci, 'everyone who works in any field connected either with the production or distribution of knowledge is an intellectual'. Said himself believed that an intellectual is an individual 'with a specific public role in society that cannot be reduced simply to being a faceless professional, a competent member of a class just going about her/his business,' and that an intellectual should act on the basis of a universal principle that 'all human beings are entitled to expect decent standards of behavior concerning freedom and justice from worldly powers or nations, and that deliberate or inadvertent violations of these standards need to testified and fought against courageously'.

In the post-1952 Bangladesh, our traditional intellectuals also assumed the public role, which Said considered essential for ensuring a nation's freedom and social justice. They risked incarceration and death to establish the principles, some of which were later enshrined in our constitution. In the 1970s and 80s, these action intellectuals continued their fight against authoritarianism and narrowing of political and cultural space. They were in the forefront of all our political struggles not only in Dhaka but also in the outlying districts where it was easier for the police and intelligence people to arrest them and keep them behind bars for as long as they wanted. But as time passed democracy (in whatever form it exists) was restored, public intellectuals began to shrink in number. Today, with political polarization affecting even our learned society, public intellectuals – giving an ironic twist to Said's description—are becoming figures of exile.

Today, as we remember our martyred intellectuals, we must ask ourselves these questions: Where have our public intellectuals gone? Why do most of our intellectuals aspire nothing more than becoming 'faceless professionals'? Our tribute to the martyred intellectuals will ring true if we refuse to surrender our conscience to the powers that be. We may do well to remember what Said has said: the role of public intellectuals is not always to challenge and take on the government on matters of policy and rights, but also to make use of their vocation to 'maintain a state of constant alertness' and to show 'a perpetual willingness not to let half-truths or received ideas steer one along.' This is exactly what the martyred intellectuals did, and what our educators, journalists, lawyers and other professionals have to do in these troubled times.

The writer is a retired professor of Dhaka University, currently teaches at ULAB and is a member of the board of trustees of Transparency International Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments