Gazir Gaan: Representation of tolerance and social equality

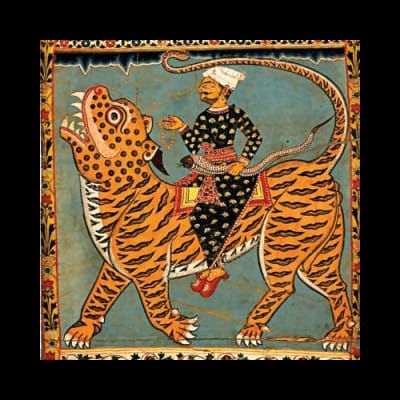

The notions of equality and tolerance are embodied in Bangla folk wisdom and music tradition. Besides the belief and practices of the Baul, some other older and ancient genres of folk music captured and ushered in the perceptions of tolerance and unity among the members of communities. One of the oldest Bangla folk music genres is known as Gazir Gaan, practiced in different parts of the country, which has got the most significant essence of this universal value. It is a form of song performed by a single individual or groups varying in diverse range of arrangements and names in different parts of the country. The performer mainly pays tribute to Gazi Pir, who is part of Pach Pir tradition of folk practice and belief where his name is attached with other four Pirs namely, Zinda Pir Khoaj (controller of water world), Badar Pir (Controller of storm), Madar pir (controller of the fire), and Shatta or Manic Pir. These Pach pirs have symbolic Mazaar (shrine) in many parts of the country. The followers of Pach Pir carry their symbols and practice their music, which is generally recognised as Pachali, Fakiri Gaan etc. These Fakirs were revered in the rural society. According to the folk belief, Gazi Pir is thought to be the controller of the animal world, particularly tigers. All local groups, who extract resources from forests including Sundarbans mangrove forest, offer Shirni (a kind of tribute) to Gazi Pir before entering the jungle. The followers of Gazi Pir describe his acts and characteristics in different forms; some demonstrate folk painting explaining it with dance and songs (known as Gazir Pot) while others do it in a ballad form. Tales of Gazi Kalu Champabati along with folk paintings are told by many story tellers. More than 70 years ago, poet Jasim Uddin collected a Gazir Gaan from a farmer living in a remote area of Faridpur. A poor farmer had sung the song as presented by Jashim Uddin:

Nanan boron gavire bhai eki boron dudh

Jogot bhromiya dekhi eki mayer put

[Cows' colors are different though the milk is of the same color

Travelling through the universe I discovered all are children of the same mother]

The notion of equality that unites humankind is metaphorically presented in this song. The Bangla service of Voice of America (VoA) in the early 50s started its Bangla transmission from Washington with it as its theme song – a fact that most of us are unaware of. However, many books were published on Gazir Gaan, Gazir Pot and Gazir Pala where authors paid attention to the form and presentation style. One of the most significant issues missed by most researchers and authors is the social function or utility of this particular genre of folk song tradition. Gazir Gaan is a symbol of tolerance of people belonging to a different religion, sect and identity. It has encouraged people to lead a harmonious life in a multi-faith society. The farmer, fisherman or representatives of any such occupational groups in rural Bangladesh used to go out for begging from door to door on particular days. They showed pictorial presentation and uttered rhymes or sang a song on Gazi Pir and tried to spread this message. I saw many of these practices when visitors of this kind came to our house in Brahmanbaria in my childhood. During my stay in Nabinagar in 1995 as a research assistant with a Swedish anthropologist, I was privileged to meet a man from Ramchandrapur who demonstrated a Gazir Pot with his performance. He had carried the same message too.

The renowned folk musician in this subcontinent called Amar Paul had sung a Gazir Gaan, which would be the best example to present here. The lyric of the song goes like this:

Akherer e kam koro koro banda koro/pirer dorgai shirni diya hawar pithe choro

dao pori bhut dana badshah Solaiman/Allahjire bhabo sathe hashorer maidan

Gazir shirni paile ami tobeto geet gai/shirni na paile tobeye bejar chaila jai

Ram Rahime juda tora karis nare bhai/ aryee Kashi Mokka ekoi gun bicharete pai

Kali thake mandirete/Alahi oi mashjidete/shondhaya annik namaj rojai kono bhed nai

[Good deed helps as the consequence of life after death, so pay respect to Pirs

Demons, fairy and ghosts are ruled by the king Solomon, think about blessings of Allah on the day of judgement

I only sing if I receive anything as respect to Gazi Pir, and if nothing is given I just go back with a sad mood

Oh brother, do not divide Ram and Rahim as they represent the entity of the same creator

Kali is meditated in the temple and Alahi in the mosque but all forms of prayers serve the same purpose]

I have interviewed Amar Paul a few times and once at his residence in Kolkata. I repeatedly asked him questions regarding this song. Amar Paul was born and brought up in a place called maijh para in Brahmanbaria and left the country in 1946 at the age of 26. A group of people representing both Hindu and Muslims called Gain used to visit his house. They used black clothes to cover their forehead and performed Gazir Gaan. He learned the song mentioned above from them.

The significance of Gazir Gaan is that it is a deliberate initiative through musical performance by the marginalised people in rural communities to sensitise its members as a whole, not to divide, discriminate and disadvantage anyone because of their religion, faith or ideological orientation. This reflects the notion of mutual respect and understanding, which is emphasised in the words of the songs they sing. 'Ram and Rahim' are two brothers and they are a symbol of peaceful coexistence like two flowers of different colours flourished on the same stalk. They exist together with coherence. It also represents the insider's view of the active tradition bearer of the given culture. This reveals the greatness of the idea and local initiatives of our ancestors to think about each other as part of their knowledge practices. Unfortunately these great aspects of folk music traditions and efforts of common people were not properly interpreted or taken into consideration by the larger group of educated intellectuals and researchers due to their biases and privileged positions in society.

The notion of tolerance and mutual respect is derived originally from the traditional belief and faith. They subscribe to people's close relationship with and dependence on nature. Many of the followers of Pach Pir deliberately subscribe to the life of Fakir or Sadhu with an understanding that derives from local esoteric knowledge. This helps them realise that valuable possessions may not help anyone much at the end of the day. The notion to survive reciprocally and collectively with limited resources without harming nature has also been derived from the concept of an egalitarian society. The Baul also emerged as a group with similar ideas but it was a regular practice among the marginalised common people from much earlier. Furthermore, the Fakir in the community had acceptance among its members because not only were they thought to have spiritual power, but they were more accommodative and tolerant and always kept space for different thoughts and practices. Later, according to the widespread notion of western standards of individual mind set since the colonial period and so on, these Fakirs were treated as 'vagabonds' followed by the British rule. Moreover, the emergence of 'bhodrolok' culture in Bangali society typically viewed those traditional practices as unsophisticated and backward. Subscription to the so-called notion of modernity and biases to technological advancement blinded us and blocked our vision from observing the significant aspects of our traditional culture. Although it is true that society changes and elements of folk practices transform, which have inevitable and greater impacts on all aspects of human life, we can still learn from our tradition like Gazir Gaan as it can help us resolve clashes and conflicts in our larger social life. Sad but true that many of the folk music genres of this kind has become extinct due to the lack of documentation, proper appreciation, unawareness and negligence. As a consequence, the process of nurturing our society and culture through such initiatives to enhance the notion of tolerance and equality gradually disappeared.

.............................................................................

The writer is Ethnomusicologist, Singer and Associate Professor of Anthropology at Independent University, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments