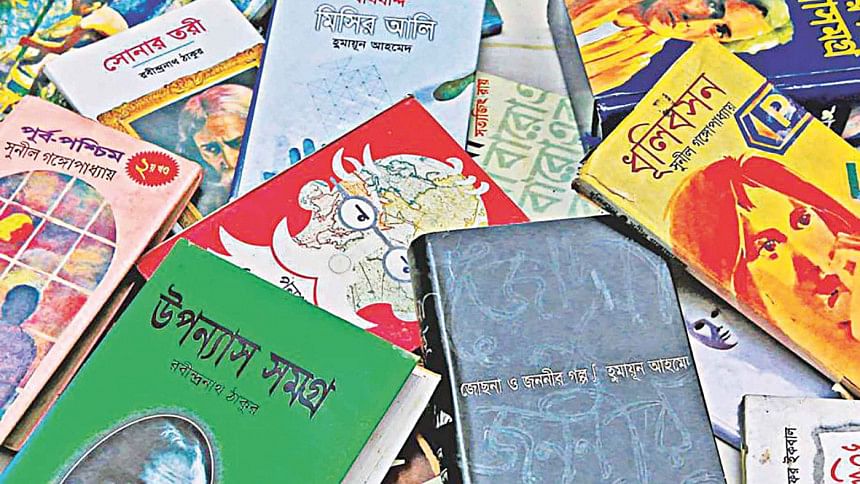

The circulation of Bangla books

While writing a text, a literary text in particular, many authors tend not to think about its afterlife. Imagining, experiencing, and putting the story down on paper takes precedence during those moments of creation. And yet a future journey for that text does emerge with or without the author's intent—for every story written, there exists somewhere a community of readers, and through the process of publication it becomes part of the larger network of produced literature. Something similar happened to the metaphysical life of the Bangla Language Movement of 1952. It was a deeply personal struggle for the close to 4 crore 40 lakh Bangla-speaking people of East Pakistan who demanded that their mother tongue be instated as one of the official state languages of Pakistan. Upon achieving success, that personal struggle became part of global history when UNESCO proclaimed February 21 as the International Mother Language Day, in 1999.

I begin with this comparison because it highlights the significant impact that circulation can make in the endurance of languages, literatures, and histories, as has been highlighted by the scholarly works of Roger Chartier, Pierre Bourdeau, or even by the ideas of Tagore in "Bishsho Shahittya", his essay on World Literature. For the past decades, translation has played a major role in this process of circulation, and for the past few years, digital platforms including virtual marketplaces and social media have all but commanded the fate of books brought out by publishers. Sixty nine years since the Language Movement, if we are to examine the performance of Bangla texts across the world, the role of these platforms in helping not only to create texts but to circulate them, is vital. I began exploring this idea with high hopes when I first decided to write about it, but conversations with publishers, editors, and book bloggers have revealed to me that Bangla literature has managed to make a very tiny space for itself in the thriving virtual world of books.

The first step, in the case of circulation beyond borders, is the consistent flow of such good quality texts. From Bangladesh, among the most laudable of these initiatives came in the form of the Library of Bangladesh series started by Bengal Lights Books edited by the Dhaka Translation Centre and author-academic Arunava Sinha, for which writer Shabnam Nadiya has translated Shaheen Akhtar's Beloved Rongomala (2019), Professor Kaiser Haq has translated Shaheed Quaderi's Selected Poems (2018), and Pushpita Alam has translated Syed Manzoorul Islam's Absurd Night (2018), among others. Rights for the books' distribution in the "Rest of the World Other Than Bangladesh" were shared with India's Seagull Books, who could then circulate them across the US and UK through the University of Chicago Press.

"The pity is that along the way, no fresh books [in the series] have found their way. This means the Library is stagnant," Naveen Kishore, publisher of Seagull, tells The Daily Star. "We need someone there who can find, scout, and curate interesting texts."

Bangladesh's University Press Limited (UPL) is an industry leader in the same operations as Seagull in terms of exchanging rights with overseas presses including Hurst Publishers, Columbia University Press, and notable others. Yet the feedback on these initiatives have been lukewarm.

"The response has been rather discouraging most of the time," UPL publisher Mahrukh Mohiuddin shares. "Quality of translations has been a factor, given that most of the translations were prepared through individual initiative and not under the supervision of a proper institution. Some form of collaboration in these projects would have had an enriching effect. Whatever little benefits we were able to reap digitally were possible through authors' personal networks."

Access to digital selling platforms is another obstacle. Whereas local platforms like Rokomari.com, online bookstores, and the use of social media have helped domestic sales, helping bypass defaulting brick-and-mortar stores, trying to sell Bangladeshi books abroad brings its own set of issues. Bangladesh cannot operate directly on Amazon. Local publishers have to arrange orders through other countries, and in most instances, the shipping and other bureaucratic charges leave very little for profits.

"The way any serious literary publishing of this nature gathers root is to build a sustained and strong backlist," Naveen Kishore of Seagull comments. "Usually small numbers across the growing backlist continue to sell over the years and make enough cash flow for you to keep doing more translations. Here the word 'cashflow' is significant. Our distribution allows us to reach the world but the numbers are small; interestingly as 'big' or as 'small' as say translations from the French or German. But you also need to keep in mind that these are of specialist interest and not every store in the English speaking West keeps them. So events and constant engagement with the social media are vital for spreading the word to the diaspora communities. The only way to succeed is to keep the list growing and at some point achieve a critical mass or a large corpus of Bangla literature in translation, not just through Seagull but also other publishers."

"If we could have some independent entity promoting Bangladeshi content globally, that would be helpful. It isn't cost effective for individual publishers to do this. We have tried and struggled," says Mahrukh Mohiuddin.

This is where social media comes in. Twitter is the realm of acquisition announcements, news updates, and slogan-sized dispatches of opinions. Facebook is fast becoming a channel for virtual book club discussions and book sales; and Goodreads' suggestions can add some exposure. But it is Instagram's bookstagram community that draws the largest traffic for a mostly young book-reading audience. Bookstagram has turned book promotions into a thriving and, more admirably, democratic enterprise. Whereas Goodreads suggestions are at the mercy of Amazon's algorithms and print spaces and opinions of critics can limit traditional reviews of books in newspapers and magazines, Instagram allows a diverse range of readers to discuss books in an informal format. The downside is that there is often less traditional literary expertise involved in such reviewing, and much focus lies on the aesthetic appeal of book covers (which publishers have been able to utilise to their benefit). Moreover, the platform creates space for more heartfelt and honest responses to books—few reviewers have professional niceties to maintain with authors or publishers, their language is more relatable and less jargon-riddled, and they often highlight how one book can appeal differently to different groups of readers.

The exchange of comments on posts, stories, and live sessions between bloggers and followers also allows for a more organic flow of ideas surrounding a book or author.

But while a search for #bookstagram brings up 56.1 million posts on Instagram at the time of my writing this article, #bookstagrambd brings up only 35,500 posts and variations of "bengalibooks", "banglabooks", and "bengaliliterature" bring up barely over 5,000 posts. And whereas podcasts, book clubs, and individual profiles promoting literatures of colour from other parts of the world, even neighbouring India and Pakistan, boast tens of thousands of followers, few profiles featuring Bangla works exist to begin with, and their follower base is substantially lower. Here, too, access and mobility deter traffic—international giveaways by publishers and bloggers often leave Bangladesh out.

"I think maybe there is a language barrier," says Samira Ahmed popularly known as The Millennial Ma, among the most popular Bengali Instagram bloggers based in the UK, who also features books. "Indian or African readers promoting local writers use mostly English to communicate. If people post bilingual captions, make most use of IGTV, reels, live sessions etc., it can work better."

If the Covid-19 pandemic had any positive effect on our lives last year, it was the drastic rise in the scale of conversations across communities. Unlike ever before in The Daily Star's history, each of our departments were organising live sessions with authors, publishers, artists, and politicians on an almost weekly basis, and unlike with print interviews, our readers and viewers could partake in those conversations through live comments. This has only proven that boundaries of geography and logistics are porous and malleable, and with some enthusiasm on the part of both parties, circulation of literatures between Bengal—comprising Bangladesh and West Bengal—and the wider world is not an impossible feat. Assistance from businesses and governments could help ease the financial and logistical barriers. As always, writers, artists, and readers can take care of the rest.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor, Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments