In conversation with Salimullah Khan, one of Bangladesh's most prominent public intellectuals and a professor in the Department of History & Philosophy at North South University.

The Daily Star (TDS): What led you to deliver the speech at ULAB on July 31, where you famously called for Prime Minister Hasina's resignation?

Salimullah Khan (SK): I don't know, really. Perhaps, when after July 16 the fascist government closed the public universities and the students of the private universities, including the one in which I work, took to the streets, a realisation like Frantz Fanon's dawned—one that may be put in Fanon's own idiom: "there comes a time when silence becomes dishonesty."

I reached the decision not to despair of human dignity—in other words, of myself. I was determined not to lose hope. It was no longer possible to keep quiet on the false pretext that there was nothing else to be done.

You know Mao Zedong's notorious adage that making a revolution is something other than writing a dissertation or delivering a fine after-dinner speech. Could what we were witnessing in late July be described in any other terms than either madness or revolution? The killing spree the fascist regime unleashed since July 16 convinced me that I owed it to myself to affirm that I had become permanently an alien—in other words, an unfree man in my own country, living in a state of absolute alienation, nay, of madness. When a regime raises the multi-daily murder of man to the status of legislative principle, what else remains to be done?

With our backs to the wall—literally—I had to be brief in my prayers: O my body, always make a man who refuses to lose his freedom to madness!

TDS: The student-led movement that ultimately toppled the long-standing authoritarian regime is widely believed to have been driven by jobless growth, corruption, and unaccountable planning. One year on, to what extent have the economy and the education sector shown signs of moving in the right direction?

SK: I do not think it is hard to say whether the economy (and also the education sector) is going. If you mean by "right" something necessary or adequate, it is not going in the right direction. But it has been going in the right—as opposed to the left—direction for a long time.

But for an interim government, reforming an entire education system must be too tall an order. Or, for that matter, reform of the whole national economy must remain illusory.

Ever since this country (and its neighbours) became part of the international division of labour with Britain and exported agricultural products, policies in the "right direction" did not lead to prosperity either in agriculture or in the industrial sector. The commercialisation of agriculture also did not improve the living standards of the cultivator.

The picture did not change much in the post-colonial age either. Public investment in infrastructure increased in absolute terms as the share of investment in GDP increased. However, with market-based economic reforms—that is, the introduction of neoliberalism—the emphasis shifted away from productivity-raising investments in agriculture, and many of the problems that agriculture faced in the colonial era have resurfaced. The country remains a nation of hewers of wood and drawers of water.

Similarly for education—especially at elementary and fundamental levels. Policies in the post-colonial age in education also show the same old colonial trends.

To this day, our primary and secondary levels of education remain the most ignored sectors and thus cannot create a literate workforce for modern industry.

Investment remains abysmal in education, and quantitative growth in tertiary education, in the absence of good secondary schools, ends up producing a perverse structure where the service sector overtakes both agriculture and industry. It will be too much, perhaps, to expect a miracle from an interim regime. They too must have known this.

TDS: There seems to be a growing surge in mob violence and crimes against women and minorities under the current interim government. Do you see this as merely a law and order issue arising from a partially functioning police force, or does it indicate a deeper societal shift—perhaps the rise of "religious extremism" in the vacuum left by the absence of a robust democratic environment?

SK: I doubt how deep a shift it reflects. It is best seen rather as a belated reflection of twilight dust flying over the tombs of our tenets of humanism. It reminds me of Iravati Karve's stricture: "It takes thousands of years to achieve humanitarian values, and one generation for them to come to dust."

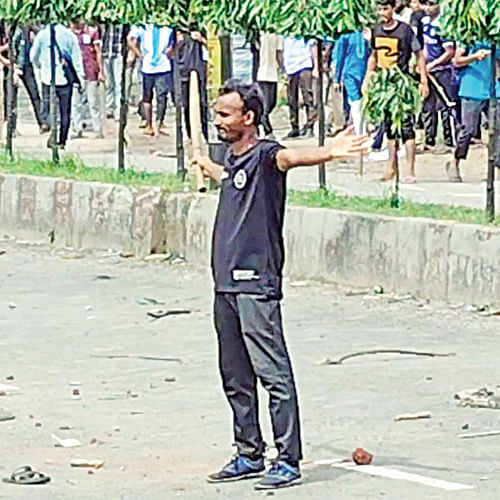

"Mob violence", so-called, is a form of anarchy, and it may be seen both as a belated reaction to the fascist violence perpetrated over the past several generations. After all, it was in the womb of fascist violence—a combine of ruling party private apparatus with the monopolistic violence of the state—that today's "mob", if not its violence, was born.

"Religious extremism", if any, also has its short-term determinants in our material existence and our psychic conditions. I wouldn't think these phenomena represent any deeper societal shift other than the legacy of a historic inferiority complex of the Bengali Muslims—one born in an era of unequal exchange with their casteist or Aryan conquerors, fostered even throughout the two bouts of Turko-Afghan rule in Bengal, and re-valorised in the darkest era of reactionary European colonialism.

What is new in it is perhaps a refraction of a belated late-neocolonialism—that is, imperialism masquerading as globalisation. It is the state of continued marginalisation of an entire nation that stalks our land, of which the mob is a perverse symptomatic expression. It also shows a spontaneity of the urban poor, a lumpen proletariat casting its long shadow on the imagination of a neoliberal elite—a parasite thriving in the shadows of an imperial climate change. All said and done, the lumpen proletariat is a product of the misadventures of our national consciousness.

What is "religious extremism" anyway but a phantasmagorical construct born in the angst of a privileged and alienated westernised minority in the country—one which, under the auspices of a reactionary fascist dictatorship, fattened itself for over half a century?

Alternatively, you might find it a revolution dissipating itself—or even entropy. In any case, a "robust democratic environment" has never been a real thing. It remains an adorable but fictitious configuration of our noisy imagination—at worst, a good bluff.

TDS: As the current government has made no move to establish an Education Commission to initiate reforms—and is unlikely to do so—what short- and long-term measures do you believe are necessary to address the ongoing crisis in education, particularly the widespread prevalence of poor and substandard quality from primary to tertiary levels?

SK: It may not be out of place here to recall that education had been a premier battleground for social mobility and political power in the British colonial era. It remains so. Moreover, it also interpellated what Partha Chatterjee aptly called Macaulay's poison tree. Those who drank their fill from these poisoned chalices now live a life of what Sartre called "bad faith"—or inauthenticity. I mean alienation.

The pitfalls of our alienated national consciousness—that oxymoron—become manifest in the lack of access to even an elementary education for all. Moreover, a national system of education could not be completed in the past eight decades. Instead, they keep shamelessly insisting on a foreign medium of instruction in the 79th year of our new statehood. What a shame!

This not only reflects the historical legacy of the inferiority complex of the Bengali Muslims but also their continuing subjugation to the ideologies of a narrow, alienated, marginalised elite.

What is needed today is perhaps a complete overhaul, which requires a great deal more productivity-enhancing investment in elementary and secondary schools. But what they are instead promoting is an alienated post-secondary education without any grounding in a national system of public education. Shame! It is nothing short of structural suicide!

The social regime in Bangladesh today is neoliberal, suicidal—that is, fatally alienated from what makes a nation thrive. These perpetrators of a neocolonial order in the country are, however, totally bereft of even a minimal commitment to humanitarian or, for that matter, national values.

Elementary and fundamental education must be based on a national language basis, to be followed by technical and professional education at an intermediate level. Only then will higher education bear fruit—if providence permits.

Colonial policies towards the non-extension of primary education (a minimum of 12 years of schooling) prevented the formation of a literate workforce in Bengal and elsewhere in South Asia. To this day, the concentration of the labour force in the service sector—but not in agriculture or industry—has proved the Achilles' heel of South Asian economies. Historians frequently argue that these factors provide a different perspective on South Korea or Taiwan.

TDS: With the nation awaiting general elections in the hope of restoring a normal political process, what steps are essential to foster the emergence of a functioning democratic culture—both within state institutions and throughout society—in the post-election period?

SK: As you sow, so you reap! The late fascist regime thrived on pentennial rigged elections and unlawful murders, and the interim regime is now prevaricating for a non-elected second chamber. It is certainly not going to break the spell of fascism, but merely transition into another.

The proportional representation they are pushing will, at best, be a form of basic democracy. People will lose their right to vote for a candidate. A dual system of voting will destroy whatever remains of the people's rights. I don't know who it is that empowered this interim administration to propose robbing our people of their fundamental right to directly elect their own representatives.

Isn't this cynicism also manifest in the provision for setting aside one-third of the chamber deputies for the president to nominate? Will this not open the floodgates of legislative autocracy? Colonial memories, indeed, die hard.

Military coups d'état in former days used to abrogate incumbent constitutions, and late fascist regimes used to hollow them out from within. And now, lo and behold, the transition team is planning a virtual constitutional coup d'état. They are pushing for a practically unelected second chamber. It will not change a hair, but merely allocate chairs to their selections—and will, no doubt, bring forth another disaster before long. They are openly offering viceregal and gubernatorial general jurisdiction to a nominal president in nominating a third of the upper chamber deputies.

The oligarchy formed by a regime of primitive accumulation will not stop anywhere, it seems, before throwing the nation to the wolves.

If a second chamber is a must, why not follow the US example? Why not form a second chamber of 128 deputies by equal representation from all of our 64 districts, gentlemen? That would address the problem of unequal regional development, including that of the Hill districts.

I cannot see how we are going to establish a functioning democratic system in the absence of directly elected representatives for both lower and upper chambers.

The problem of a functioning democratic system in Bangladesh does not lie in whether we adopt a presidential or a premier-led form of government. It lies in the equitable distribution of not only political but also economic resources. There will be no peace without health.

What do our lived experiences with presidential and premier-led systems in the recent past show? We have seen both leading to autocracy and, ultimately, fascism—haven't we? The incumbent neoliberal regime's prevarication game with electoral reform—by building a consensus without electing a constituent assembly—is a sham and is going to be disastrous. Has it not already become manifest in the myriad reform commission reports produced by the regime? I am afraid their fate will be no different from those of the numerous task force reports of 1991. Only a providence, perhaps, can save us from the sharks.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

Comments