THE UN'S SILENCE

Despite history's numerous precedents, the word “genocide” did not exist until legal scholar Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew who found shelter in the United States, coined the term in 1943. On December 9, 1948, the UN unanimously adopted a convention on genocide, identifying it as a crime “committed with the intention to destroy in whole or part a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Called The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, it was adopted by the General Assembly on December 9, 1948, and came into effect on January 12, 1951.

The word “genocide” that gradually entered the lexicon of international law has been used to officially characterise the mass slaughter of Armenians, Jews and Rwandans in the 20th century. The UN recognised as genocide the killing of hundreds of thousands of Armenians between 1915 and 1917, the mass murder of Jews by Nazi Germany during World War II, and the killing of an estimated 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis by their Hutu compatriots in 1994.

Genocidal expert A. Dirk Moses (August 27, 2010) claims, “In 1971 Pakistan Army's brutal, indeed genocidal, suppression of the East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) autonomy/independence movement received more international attention than any other of the above-mentioned cases, yet nothing was done by the UN or nation states to interdict, let alone condemn, the killing”. The term “genocide” was used extensively by eyewitnesses, journalists, and politicians throughout 1971 and subsequently to describe the mass killings in Bangladesh. And for the first time since Nuremberg and Tokyo, war crimes trials were seriously considered, in this case by Bangladesh in 1972, which wanted to prosecute numerous Pakistani soldiers and their local collaborators. The trial issue was even listed at the International Court of Justice in 1973, the first time that such a thing had occurred.

It would be relevant to look back at how the international media reported the massacre. On March 27, 1971 the American Consul General in Dhaka, Archer Blood, sent a telegram to Washington headed with the phrase “Selective Genocide”. The New York Times editorial of April 7, “Bloodbath in Bengal,” condemned Washington's silence on what it called the “indiscriminate slaughter of civilians and the selective elimination of leadership groups in the separatist state of East Bengal.” Only a day earlier, with the carnage continuing without condemnation from the White House, Blood and twenty-nine diplomatic colleagues sent another telegram from Dhaka – the celebrated “Blood Telegram” – to the State Department headed “Dissent from U.S. Policy toward East Pakistan.” This unprecedented cable is worth quoting, at least partly: “Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities. Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy… But we have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awami conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, on the grounds that it is purely an internal matter of a sovereign state”.

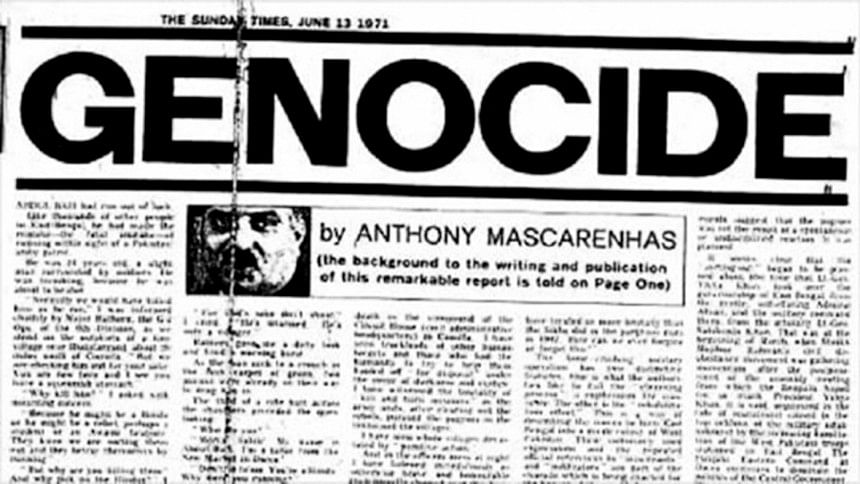

Peggy Durdin, in a piece in The New York Times in early May, called the killing “one of the bloodiest slaughters of modern times.” The breakthrough came in mid-June when Anthony Mascarenhas, assistant editor of the Morning News in Karachi and an official war correspondent attached to the 9th Pakistani Division in East Pakistan, fled to London to report what he had seen. The Sunday Times devoted a long article in his own words and an editorial, both under the prominent headlines of “Genocide.” An editorial in the Hong Kong Standard spoke of “Another Genghis!” a few weeks later, playing on the fact that the Pakistani military general was named Tikka Khan. “Tikka Khan and his gang of uniformed cut-throats will be remembered for trying to destroy the people of half a nation,” opined the daily. In the backyard of the UN headquarters, on August 1, 1971, The Beatles organised 'The concert for Bangladesh' in front of a 40,000 live audience to raise international awareness about the genocide in Bangladesh. Senator Edward Kennedy, the influential American politician, was one of the first international figures to alert the world of the Pakistani army's genocide in Bangladesh.

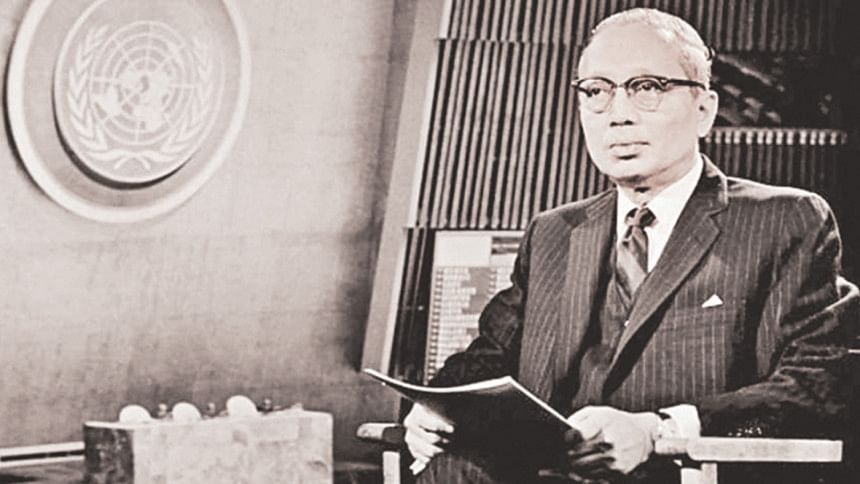

On June 3, 1971, U Thant, Secretary-General of the United Nations, wrote to the President of the Security Council, saying, “The happenings in East Pakistan constitute one of the most tragic episodes in human history. Of course, it is for future historians to gather facts and make their own evaluations, but it has been a very terrible blot on a page of human history”. However, the UN engagement on East Pakistan, then, was driven by humanitarian, not human rights, issues. But the Security Council never took the hint of U Thant and did not explicitly consider the situation on the subcontinent until an outright international conflict was on its hands in December, when India joined the war in favour of Mukti Bahini (Bangalee freedom fighters). However, the Security Council's effort was directed towards ordering a ceasefire to maintain the status quo which was tantamount to letting the genocide continue. It was successive Soviet vetoes that enabled the combined forces of India and Mukti Bahini to bring the perpetrators of the crimes to their knees resulting in the birth of Bangladesh, thereby bringing an end to the genocide. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) met in April and September of 1971 but did not seriously consider the genocide in Bangladesh either. The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) did not even issue a statement of concern and condemnation under the pretext that its role did not extend to 'internal questions' of a member country. An exasperated Indira Gandhi tried unsuccessfully to rebut the 'internal question' arguing, “It is not just a small part of the country that is asking for rights. It happens to be the majority of the country, not a small part wanting to go away.”

Since then 44 long years have elapsed and in line with U Thant's observation that 'it is for future historians to gather facts and make their own evaluations', numerous books were written, and seminars and workshops were held in many parts of the world, including many US universities, demanding the UN to recognise the genocide in Bangladesh. Bangladesh genocide is included in the curriculum of many US and Canadian Universities. An international conference on 'Truth and Justice' in Dhaka in July 2009 called the UN to recognise the mass killings carried out during the 1971 Liberation War as genocide.

In his recently published, award winning, much acclaimed book, Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger and A Forgotten Genocide, based primarily on the declassified White House tapes, reporter-turned-academic Prof Gary Bass of Princeton University wrote, “This book is about how two of the world's great democracies—the United States and India—faced up to one of the most terrible humanitarian crises of the twentieth century. The slaughter in what is now Bangladesh stands as one of the cardinal moral challenges of recent history… In the dark annals of modern cruelty, it ranks as bloodier than Bosnia and by some accounts in the same rough league as Rwanda.”

Yet, UNHRC is unperturbed by the genocide that remains unrecognised—the killings of three million unarmed civilians—notwithstanding the fact that Guinness Book of Records listed the massacre as one of the top five genocides in the 20th century. Quite to the contrary, it is sparing no opportunity to condemn the trial process of Bangladesh's International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) where the convicts were given all avenues available in the due process of law. In a statement issued in Geneva on November 19, a spokesperson for the UNHRC said the government should not implement death sentences awarded by ICT, “given the doubts that have been raised about the fairness of trials conducted before the tribunal.” The latest statement came in response to the recent execution of two war criminals. Regrettably, without expressing any compunction for its inaction in 1971 to side with the victim, the UNHRC is now expressing its concerns for the perpetrators whose offences, in the words of ICT presiding Justice Obaidul Hassan, “indubitably fall within the kind of such gravest crimes which tremble the collective conscience of mankind”. If UNHRC could keep itself mum in the pretext of 'internal question' of a sovereign country, when three millions unarmed civilians were brutally annihilated, does it now possess the moral right to express its concerns about the open trial process of ICT and the execution of a few convicted war criminals through due process of law, which, by the way, very well is an 'internal question' of a 'sovereign country'?

The writer is the Convenor of the Canadian Committee for Human Rights and Democracy in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments