Escape to Freedom

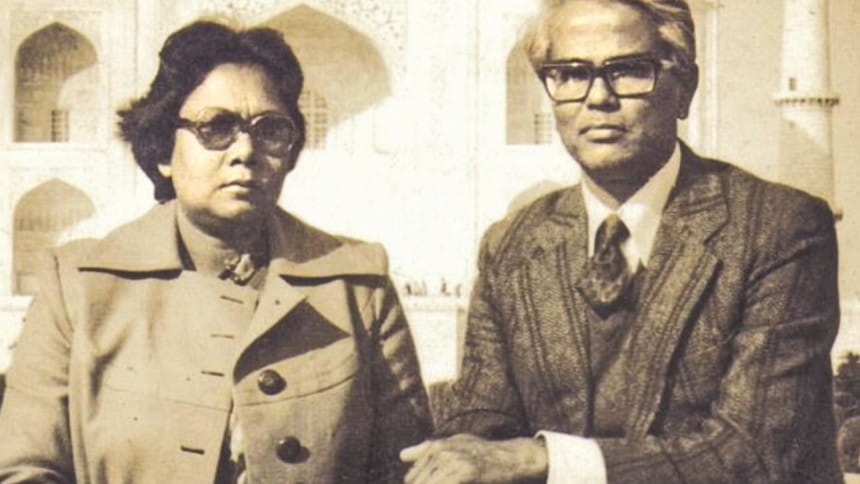

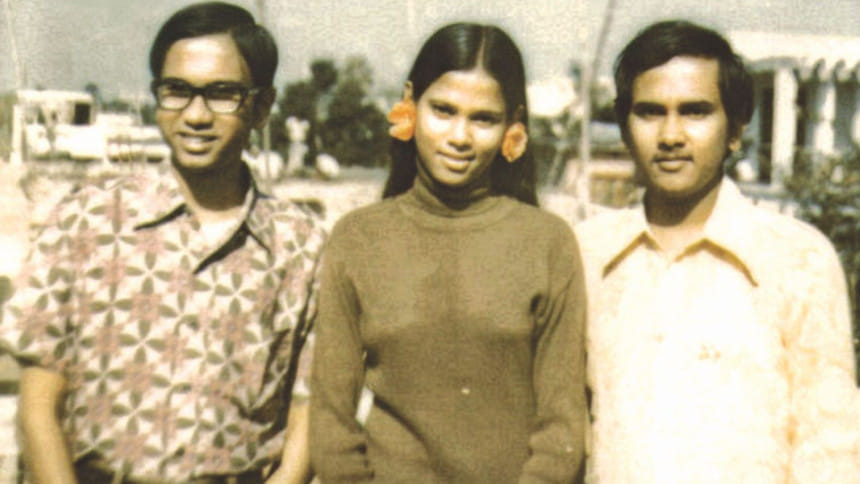

It was March 1970. My husband, Aminul Islam, came to Islamabad on a posting to Pakistan Central Secretariat. I accompanied him with our two sons aged 15 and 13 and daughter aged 10. It was a comfortable living in Islamabad and we were all happy. But little did we know then that we had to be literally smuggled out of Pakistan to freedom in less than three years' time.

What happened was this. Bangladesh was born on December 16, 1971 after a brief nine-month war of Liberation waged against Pakistan. The emergence of a new country in the eastern wing of Pakistan after a lapse of 24 years following partition of India was a unique event and meant a big change in the entire Bengali population living mainly in the twin cities of Islamabad-Rawalpindi and Karachi. Because of our origin, we became aliens in the eyes of the authorities there, overnight. Those working for the government were gradually laid off and given a pittance in lieu of salary.

With rare exception, we all opted for Bangladesh to work there, and build a newly independent country of our own. The process of sending us back was, however, being delayed due to various complications; mainly on the question of repatriating a large number of Pakistani troops being held back in Bangladesh as POWs.

We still had our jobs and had not been fired. The date was March 26, 1971 and one can imagine what our mental state was on that date. The newspaper headlines screamed that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been arrested at the airport. My husband had become very agitated upon hearing the news on the BBC on the night of March 25. He became sick with fever and was running a temperature of 106 degrees. I thought he was delirious when he kept saying: “We will have our own liberation army!” It turned out that he was right. He was fired from his job earlier. Because there were a few Bangali officers who did not enjoy the confidence of their Pakistani bosses, like Secretary A.K.M. Ahsan, who was not given any meaningful work in the service because he was considered pro-liberation. The same happened with my husband. Before they could resign, they were told not to attend office.

Thankfully, I still had my job then. My personal experience in college was not pleasant. I used to teach at the Federal College for Women. Students came from both East and West Pakistan to study. The number of women from East Pakistan was naturally few in number. Most were Punjabi, Sindhi, but mostly Punjabis. The few Bangali teachers that were there, all of us were sad because of the prevailing circumstances. One experience stands out from the rest, one which I remember even after all these years.

It was March 26, 1971 and mentally devastated though I was, I went to take my class. A Punjabi student stood up and asked me “Madam, if somebody wants to secede, what is the punishment?” I felt very indignant at the question and wanted to shout out a response. But that would have been suicidal and hence my reply was thus. “Ok, Mr. Jinnah wanted to secede and he was successful. If you are successful, then you become a hero. Mr. Jinnah became a hero and if you are not successful, then there is punishment of course.” And this had to be delivered in a calm voice keeping one's composure. The next day I got a letter from the Education Board relieving me of my services. The principal called me to the office and said “Mrs. Islam, please don't come to the college from tomorrow. The situation is very bad. There is a complaint against you.” And other Bangali colleagues informed me that I would get beaten up if I came to the college.

About 3-4 days after that, my husband told me that some of my students had come to see me. I was wondering that perhaps I had some notes belonging to students and they had probably come to collect those. They came back and asked “Madam, Bengali lok wa ke Hindu hey?” (Are Bangalis over there all Hindu?). This was a question that they asked repeatedly. I replied, “Don't you know? My husband is Aminul Islam. You cannot make out from the surname? Does he sound Hindu? Fazlur Rahman, Ziaul Haque, they are all Hindu? Can't you make out from the surname? And you people, Junjua, Bajoa, Rathore, Rajput, Yasmin Rajput, Bushra Rathore, they are all Muslims, aren't you? My husband was scared because he thought this time they would rough me up. My son came to the rescue and asked them to leave and not to bother me since I was already very upset with everything. Incidents like this made my life quite miserable.

We both lost our jobs. We were given a stipend of Rs500 per family (not per head) to survive the month. We were however allowed to stay in the government quarter. Authorities cut off the telephone connection. My husband, Mahmood Aminul Islam was, at the time, Deputy Secretary in the Agriculture Department.

In fact, we became pawns to be used in an exchange for those POWs with Bangali civil and military personnel serving in Pakistan. As days passed by, the situation was becoming unbearable for us. We did not have enough cash for a decent living, and had to remain confined in the same place against our will. We did not have access to direct postal or telephone link with Bangladesh, further contributing to our isolation and mental depression. We all felt like virtual captives.

The Rs 500 was simply not enough to survive and we started to sell our fixed assets. The TV went to pay for one month's survival. Another month we sold the refrigerator. Then went the fine crockery, decoration pieces, etc. and in this manner we were helping to feed ourselves. All Bangali families in our situation were doing the same. The last thing of value we had was our car.

So I thought if we sold the car and ate up the proceeds, then what would we do for food? We were already going through a lot of emotional turmoil. The children of all pro-independence Bangali families were expelled from school. They were loitering about with nothing to do. We were worried about them. That they would grow up as illiterates. Then what would they do in life? Do menial jobs in life?

When we were in this desperate mental state, news reached me in mid-1972 of a few instances of Bangali families successfully escaping to Kabul, Afghanistan using the route through Pak-Afghan border on their way to Bangladesh with the active help of some influential local people of the Pathan tribe.

I carefully listened to those stories and after discussing with my husband and children decided to follow their example, come what may, before we were taken to the proposed detention camp and held there till we could be sent back. Soon, we established contact with one of them, directly involved in organising these escape operations. He demanded Rs. 10,000 then roughly equivalent to USD4,000.00 for his services. Fortunately, we had some ready cash, the sale proceeds of our car, and the deal was made. Right at this time, a young, robust Bangali gentleman with his 14-year-old daughter volunteered to join our group. This proved to be a boon for us.

As the time of our secret departure from Islamabad was approaching, I was getting very worried about our personal safety during the flight. How prudent would it be to repose complete trust on total strangers who would take us across the desolate mountain path towards the border during night. What, if they betrayed our confidence and try to be nasty especially to the two young girls?

He also left detailed instructions about the precautions that we must take while travelling the stretch by train – no luggage except a small hand bag, absolutely no conversation amongst us, and no carrying of any photographs or certificates – and we should all be dressed in a manner indistinguishable from others in the compartment, so as not to compromise our identity in any way. We were to get down one station before Peshawar main station, and rush to the marked car (with its engines on start and running).

What an irony of fate! With the political change, we had turned out to be subversive elements from loyal citizens, and now being compelled to flee the country. On the appointed day, February 28, 1973, our fateful journey to freedom began. We got up well before dawn, had a quick wash in candle light, and left for Pindi railway station in a taxi, ordered the previous night. The train was on time, and we started early in the morning accompanied by our friend and his daughter. We reached Peshawar cantonment station around 9am, hurried to the car waiting just outside the platform, and crammed (all seven of us) ourselves in it.

The driver at once released the clutch and started moving along the main city road, diverting almost immediately to an unpaved side road. After we had covered some distance, we saw somebody frantically waving the car to stop. Instead of stopping, the driver took the car to an open wheat field and continued driving. As he explained later on, the man with the flag was there to warn us not to proceed along the road to preclude any chance of being caught by police. It was sheer good luck that we got the timely warning.

After about two hours of bumpy ride, we reached a village far into the non-regulated tribal area by the side of a hill. Four local people received us and immediately took us inside a cave. We were told that this had been done for our safety. There were many rival clans living nearby and we, as guests of one clan, might arouse jealousy in others, provoking unfriendly acts. Inside the cave, we ate some boiled eggs and bread that I was carrying in my hand bag. It was very timely since we were famished. By this time, it was late afternoon and we were asked to start walking deeper into the tribal area towards the border. After about two hours we took shelter in a thatched hut for food and stay for the night. The host provided two straw beds and two blankets for all of us. As for dinner, each was provided two thick chapatis and two green onion stems. The food was not adequate for our taste, but heartwarming, considering we were in a far-flung inhospitable territory.

We passed the night peacefully. Next morning, after finishing the morning chores and eating a simple breakfast, we left on foot accompanied by our guides. Within two hours we reached the foothill to start the more physically challenging and hazardous part of the journey. A distance of some forty miles of lightly forested hilly terrain was to be covered on mule backs, both during day and night. The whole proposal seemed gloomy to me and I thought I could never make it. But the gentleman who unexpectedly joined us in Islamabad offered to carry me on his shoulders to help me negotiate any difficult patch and he did it with ease. It was luck again that favoured us!

Each one of us was given a mule to ride in a single file. A man was assigned to each mule who was holding the bridle to guide the beast along the narrow and dangerous hilly path. We commenced our journey in the afternoon around 2pm and it went on and on. The road seemed to be unending in the darkness of the night. And to add to our hardship, halfway through, it started to drizzle that turned into light snowfall under the sub-zero temperature of early March. It was freezing cold and I could hardly move my limbs. What was more worrying was that from time to time I was losing sight of the two girls who were riding singly with their respective guides. This plunged me into worst fears about their safety.

A little before dawn, after trekking continuously for over ten hours we reached a forest clearing. We were promptly taken to an inn perhaps kept open to receive unusual travelers like us. To our surprise, we found the inn comfortably heated by a slightly embedded fireplace of burning embers, placed centrally in the room. The warmth helped us to recover from the paralyzing cold and revived our spirit. I was so glad to see the two girls and the two boys after a while sitting around the fireplace, safe and sound.

After about an hour's rest at the inn, we resumed our journey. It was now dawn and we were gradually descending into a river valley surrounded by tall hills. On reaching the plains, we dismounted from the mules and started walking along the river bed. Soon, it was day-break. The morning light was very refreshing and made us all happy. We continued walking for another two hours and reached a small market place, used as a loading point for trucks to carry commercial merchandise to Kabul and other places. While waiting there, we helped ourselves to tea and snacks at the local tea stall. Here we were told to get ready for the long journey by truck to Kabul which would take the whole day and part of the night.

It was about ten in the morning when a truck came to pick us up. The truck was already loaded with merchandise and we were asked to clamber up and sit on the top of gunny bags containing rice, sugar, wheat, flour and other commodities. It was pretty uncomfortable, but with our buoyed up spirit of freedom we didn't feel the inconvenience much.

We started a little before mid-day and the truck sped along the main highway to Kabul. On several occasions the truck stopped to allow us to stretch ourselves and have food. It was about midnight when we arrived at Kabul after covering a long distance. The truck took us to the hotel, pre-arranged for food and accommodation of Bengali escapees from Pakistan, by courtesy of the local Indian embassy. We were warmly received at the hotel and allotted two rooms, one for the five of us and the other for our friend and his daughter.

Next morning, my husband went to the Indian embassy and got all of us registered for repatriation to Bangladesh. After a week in Kabul, we flew to Delhi as arranged by the embassy. We stayed there for a few days in an officially rented accommodation before taking a morning train to Kolkata. The train was over-crowded and we travelled for the whole day and through the night to reach Kolkata. From there I rang my father in Dhaka to convey the good news of our escape with a request to arrange for our flights back home. He was overjoyed to hear my voice once again. After several days of interesting stay in Kolkata, we flew to Dhaka on March 19, 1973 after passing 20 thrilling days on the road.

Thus came to an end the saga of our audacious journey to freedom with the entire family intact. Looking back, I sometimes wonder whether trekking through the treacherous mountain trail in the company of total strangers to come to Bangladesh, when so many other families like ours were languishing in Pakistan, was worth the risk. The whole harrowing journey could have resulted in a major tragedy. But then, I desperately wanted to be back in my own country, which snatched independence after a heroic struggle and tremendous sacrifices.

The writer was Associate Professor and former Head of Political Science department, Titumir College (now University).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments