Bangabandhu and Bangladesh: Breaking the shackles of post-colonial order

Two big celebrations are knocking at our doors: one is the birth centenary of the Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in 2020, to be followed by the fiftieth anniversary of the emergence of Bangladesh in 2021. The two celebrations will not only follow each other, historically they are also merged together. The birth of Bangladesh was termed as a brutal birth by the famous photographer Kishore Parekh in 1972. Even after three decades, in 2002 when the US Consul General in Dhaka, Archer Blood, published his memoirs of those turbulent days, the title of his book was “The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh”. Brutality and cruelty are the birthmark of the emergence of Bangladesh. Obviously, Bangladesh had to pay a high price for its independence because Bangladesh defied the Pakistani state oppression and the international state structure, both rooted in the colonial legacy.

“Independence” and “emergence” are two key words rooted in the history of Bangladesh. On the other hand, if we juxtapose 1971 with 1947, when the long colonial rule ended in the sub-continent, the dissimilarities are surprising. The colonial rule ended with the partition of India and the establishment of two separate states: India and Pakistan. Their independence was not the culmination of a war of liberation, rather it came through negotiation. The 1947 independence is usually paired with the word “Partition”; many people refer to those days as partition days. This is the fundamental difference between the independence of 1947 and that of 1971.

The emergence of Bangladesh was a denial of the partition and division based on the so-called two-nation theory. It was the negation of the attempts to give permanency to the rift between Hindus and Muslims of India. Bangladesh was a denial of the process of conflict that played havoc with the lives of millions. This has been reflected in the core values of the independence struggle of Bangladesh, which was also the life-long mission of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, to uphold the right of self-determination of the Bengali nation—a nationalism based on secular ethnic-linguistic identity that embraces all religions and thereby promote unity in diversity. In this sense, Bangladesh moved beyond the colonial hangover, confronting its legacy. Bangladesh established a state that by itself denied the colonial map-making. Srinath Raghavan in his book “1971: The Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh” has rightly pointed out: “The Bangladesh crisis may have occurred during a watershed moment in the cold war, but it was [a] harbinger of the post-cold war world.”

What Srinath Raghavan has termed as the harbinger of the post-cold war era has been ushered in by Bangladesh as the map-changer of the post-colonial legacy. With the rise of national liberation movement in Asia and Africa, we have witnessed the crumbling of the colonial empire and the rise of new states. But according to the political scientists, most of these new states followed the boundaries determined by the colonial rulers. In case of Pakistan, it was unique when the politicians partitioned the land and drew the map anew, again a colonial map with boundaries determined by a judge from the mother country which heaped together the two distant parts of the subcontinent into a single state separated by more than a thousand miles of Indian territory. Now looking back from a historical distance, this may sound absurd to many but this became the order of the day. Pakistan was established as a sovereign independent state with international recognition. Pakistan as a state was a created one; there was no struggle for its independence, no image or map of the country existed prior to the one drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliff. There was no liberation struggle for Pakistan. Its leader Barrister Muhammed Ali Jinnah had never been to jail while his other colleagues from opposing parties had always been in and out of jail.

On the contrary, the emergence of Bangladesh was a defiance of the artificial state of Pakistan imposed upon the people. Bangladesh brought change in the global map of sovereign states which was sanctioned by the global community.

In a recent book by Jan C. Jansen and Jürgen Osterhammel, titled “Decolonization: A Short History,” published in 2017, the authors observed, “Decolonization’s momentous legacy consists in having translated borders between colonial states into international borders between nation-states. The result is that almost 40 percent of the length of all international borders today have been originally drawn by Great Britain and France.”

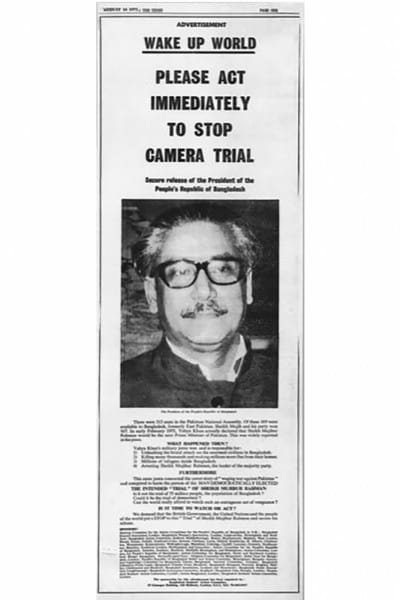

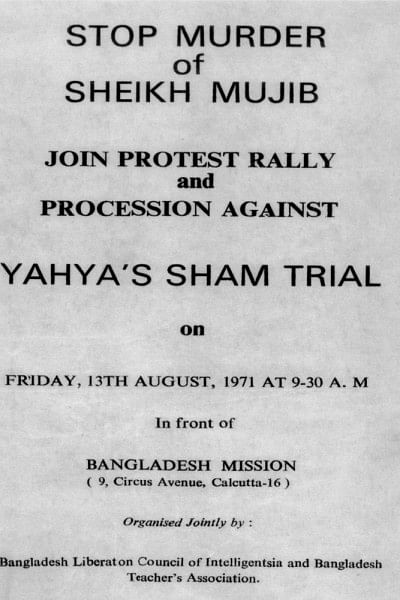

The post-colonial borders remained static but that does not mean it was a success. The recurring border disputes and clashes proved it to be an explosive legacy. The multiethnic and multireligious reality of many states resulted in conflicts, and in a few cases culminated in the genocide of their own people. In case of Bangladesh, the end of colonial legacy proved to be bloody, brutal and cruel, because of Bangladesh breaking the international order imposed by the global power. It was the wisdom and far-sightedness of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman that opened the path towards freedom for Bangladesh. Right from the beginning, he adhered to the constitutional process but also kept the other options open. The 1970 national election was the culmination of this constitutional struggle when he received the mandate of the Bengali people for the realisation of their national rights. This struggle was in line with the rights of the oppressed people for self-determination as endorsed by the United Nations in the 60’s. The struggle for Bangladesh was not a secessionist movement, unlike that of Biafra which failed in 1970, immediately before Bangladesh’s war of independence. The mandate of the 1970 election provided the legal basis for the Bangladeshi struggle. The historic March 7, 1971 speech of Bangabandhu was based on this legal and moral foundation, backed by the will of the people, which moulded into a solid unity not to be seen anywhere in the past. That was the day when Bangladesh as a state in mind was born. Bangabandhu, at the same time, prepared the people for an armed struggle should the Pakistani junta resort to a military solution for the political problem. The nation got prepared and when the Pak Army resorted to brutal force, Bangabandhu declared independence and the nation jumped into the war of resistance with whatever weapon they had.

In 1972, immediately after independence, a delegation of the International Commission of Jurists visited Bangladesh to make a legal study of the emergence of the country and recommend

ways to establish justice for international crimes. They observed, “In our view, it was not in accordance with the principles of the Charter of the United Nations for a self-appointed and illegal military regime to arrogate to itself the right to impose a different form of constitution upon the country, which was contrary to the expressed will of the majority. As the army had resorted to force to impose their will, the leaders of the majority party were entitled to call for armed resistance to defeat this action by an illegal regime.”

National poet Kazi Nazrul Islam represented both the rebel and the lover. Likewise, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib became the supreme leader of the democratic struggle as well as the armed resistance based on the internationally recognised principles. “A democrat and a revolutionary mingled into one” was the unique characteristic of Bangabandhu, a flute in one hand and a bugle on the other. Hiren Mukherjee, the leftist historian and essayist of West Bengal, in an essay on the emergence of Bangladesh eulogised Sheikh Mujib quoting a line from Rabindranath Tagore, “Dekhi Nai Kovu Dekhi Nai Emon Tarani Baoa” (I have never seen a boatman plying with such beauty).

But the ultimate tribute to the significance of the emergence of Bangladesh came from the co-authors of the study of decolonisation, Jan C. Jansen and Jurgen Osterhammel, who wrote, “Except for a very few cases (Bangladesh and recently South Sudan), attempts at secession from post-colonial states have failed—not least due to the lack of international recognition.”

The leadership of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in making the Bangladesh struggle successful requires deeper study to understand its national, regional and global significance; the same is true for the nation-state he established. The two forthcoming anniversaries have thus a great significance, at home and abroad, in the backdrop of colonial legacy and the successful case of confronting the distortion and division it created.

Mofidul Hoque is a war crimes researcher and trustee of the Liberation War Museum.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments