1971: PN Haksar in bridging the security gap

My first meeting with Mr. P N Haksar took place at his residence at 9 Race Course Road, on 30 May 1971. It was a Sunday, 11 in the morning, five days after I reached New Delhi, looking for better understanding of India's Bangladesh policy.

Perhaps a little background information is required why I went to Delhi. I was in Dhaka till 3 May, and worked with a small group to help organize the resistance movement. By the end of April, as resistance within the country thinned down, our group's activity required a meaningful focus. It was important to know if the exile government, hardly two weeks old, would be able to reverse the decline of armed resistance, mobilize enough external support to continue the struggle for independence and, also, if they would need any specific services from our group.

Accordingly, I crossed the border near Agartala, and reached Calcutta hoping to meet Bangladesh's Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed within the next few days and return to Dhaka. I met him on 12 May, only after he returned from his second trip to New Delhi, along with his cabinet colleagues. We had a long discussion on that day and the next day, as he wanted to know all the details seen and perceived in Dhaka. He gave me a brief rundown of the promises of help he had received from Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the progress his new government had made, and touched on a few thorny problems, including lack of political cohesion, hindering war efforts. On the whole, in his view, things were improving, and without giving any details, he hinted that a new phase of insurgency would soon begin, but wondered how Pakistan would react to it.

Since the formation of Bangladesh Government, a prognosis was going round in Pakistani circles in Dhaka that, in the next phase if an Indian-backed insurgency reached a threatening dimension, Pakistan might have to declare war against India, upon ensuring China's tactical intervention along India-China border. India had no such ally; its north and north-eastern borders with China were vulnerable, its military strength was not known for its capabilities of fighting war at all the three fronts simultaneously. Would India take a huge risk to its own security by continuing to support the liberation war beyond Pakistan's tolerance level? Tajuddin acknowledged a problem there. Would India be able to bridge the security gap on the northeast by seeking Soviet Union's support whose large army was kept deployed along the disputed north-west border of China? Tajuddin did not have a view. Or, would India let the refugee inflow to pile up further, which by then exceeded four million and be coerced to accept a US-brokered compromise with Pakistan? Please go to Delhi, and try to find out the answers to all these, Tajuddin said finally.

That called for quite a few more sessions, shelving the plan for my returning to Dhaka. The only option that appealed to us was to try for a security arrangement between India and the Soviet Union to restrain China from extending help to Pakistan. Would India agree to promote such security arrangement with the Soviet Union? Could we make our struggle for independence a little more acceptable to the Soviet Union by involving CPB and CPI, who had endorsed our cause? At that point of discussion, Tajuddin suggested that I should see P N Haksar, Secretary to the Prime Minister, in New Delhi and he wanted to send a word to him to that effect. Why particularly him, I wanted to know, since I heard that he took a negative stand when some of our cabinet members pressed for recognition to Bangladesh during a meeting with Indira Gandhi in New Delhi hardly a week ago. Because, explained Tajuddin, they were facing enormous problems, which we cared least to understand, and moreover Haksar was the key person needed to be convinced first before a proposition had reasonable chance of progressing further. I would meet him, I said, but a little later, let me first find out the details of their policy and what pressures it was encountering.

On board the morning flight to New Delhi on 24 May, next to me was sitting Professor Daniel Thorner, who was posted in Dhaka as a Ford scholar, and was known to me for his very helpful role during the turmoil. Even without knowing why I was going to New Delhi, he volunteered a few names worth talking to in order to understand how Indian policies were responding to the evolving situation. As he mentioned Haksar's name, I enquired if he knew him well enough? Sure, from 1939, when the two of them plus Krishna Menon and Shelvankar used to roam in and around Gower Street to share some radical dreams in the backdrop of gathering clouds over Europe. But if I wanted to see Haksar, he came back to the present, an appointment could be fixed soon enough. Daniel's second and most generous offer that morning was his invitation to share the guest room he was going to occupy in New Delhi. Barely half an hour later, at the airport baggage collection point, he introduced me to the host Dr Ashok Mitra, Chief Economic Adviser to the ministry of finance, a man of profound knowledge and integrity, on whom I started counting to steer my way through in Delhi's power-centric terrain. And the door of his house at Lodhi Estate was always kept open for all my subsequent visits.

To feel New Delhi's political temperature, I decided that morning to venture out to the office of the Hindustan Times. Daniel volunteered to come with me. Luckily editor B G Verghese, whom none of us met before, was available and he responded with frankness to my opening shot: what's next as the euphoria over Bangladesh was nearly over? After a round of inconclusive discussion on hard policy choices India was facing, Verghese made a generous invitation to interact with a small group of people having diverse views on the same subject over dinner next day.

Next morning I visited the CPI headquarter, and listened to an assessment on the current situation made by two senior leaders, Comrades Bhupesh Gupta and Krishnan. They were of the view that a policy of helping the Bangladesh liberation struggle, was growing lately; and the 'pro-American lobby' within the Indian government was exerting tremendous pressure to seek political settlement with Pakistan through American mediation. I accepted their assessment, but also wanted to know what would happen if the lobby favouring 'political settlement' failed to effect a policy change in New Delhi? Would not Pakistan try its next option to derail the liberation struggle by starting a war against India and, worse still, try to manoeuvre China to start conflicts along India's north-eastern frontier? If China was tempted to play such role, would not the Soviet Union, with its huge army mobilized along Chinese northwest border, put a little pressure to restrain China? The matter had not progressed that far, in their view, but if it did, India should take the initiative for asking for appropriate help from the Soviet Union. I could not help inferring that India had not taken such initiative till that time.

In the evening, editor Verghese organized a rare opportunity to listen to a wide variety of views at the residence of The Times of India's resident editor Giri Lal Jain, whose forthright views made me aware that the main crisis, according to changing public perception, was how to address the growing refugee burden, rather than helping the Bangladesh liberation struggle. The view of editor Narayan, of left leaning The Patriot, was more comforting to my ear, but did not dispel doubts that the existing policy could adequately cope with the evolving crisis. K Subramanium of IDSA handled, with professional objectivity, the problem of unabated refugee influx and its immense capacity to ignite a major security crisis. G Parthasarathi, probably the most informed man on policy in that crowd, raised more questions having a bearing on Pakistan's capacity to resolve the political mess it had created, the prospect for rapprochement between Sheikh Mujib and General Yahya under US sponsorship, and also ways to revive the liberation struggle in the near future. Before parting, he quietly invited me to his residence next evening.

During the next evening at GP's residence, I met a smaller crowd, only two apart from the host, and closer to the centre of power: Indian planning minister C Subramanium, and the foreign secretary TN Kaul. I kept my expectation level low about getting hard information from people involved at the policy level and also tried to avoid speculative areas in answering their questions. In short, no brain storming like the previous evening. But it was interesting that some of the questions raised the previous evening, were raised once again by GP, perhaps he wanted to hear the same answers along with his guests. From all these discussions, I got the impression that even at the higher policy level, the existing policy on Bangladesh was not being perceived as something adequate or sustainable.

Next day after lunch hour, as I came back to Mitra's residence, I met an unexpected visitor waiting for me, who introduced himself as Major General B N Sarkar, Military Secretary to the Chief of Staff of the Indian Army. He showed an unusual interest to hear my ideas on how to set up a political infrastructure to help launching resistance operations inside Bangladesh. He unrolled some old survey maps of East Pakistan and wanted to know the prospective targets for insurgent operations, nearby political bases for support and sanctuary, distances from the border, communication routes, etc. His second visit after two days made me think that some kind of staff work was perhaps on, and not everything was in a state of flux. The same evening Daniel told me that P N Haksar had invited us 'for a coffee' at 11am next day. I assumed that the actual time for discussion might not be that long, and, hence, I jotted down the issues that Tajuddin wanted to know, but with modifications in the light of the information I gathered during last few days.

PNH was very warm and happy seeing his old friend Daniel, but did not let me feel that I was less welcome. It was his weekend too, so with rest of his family, wife and two teenage daughters and Daniel around, family matters were touched upon, before he smoothly glided into the field of civil war, making it easy for me to speak. I started with a brief narration of my journey, during last one month, through three different cities Dacca, Calcutta and New Delhi; and how with the change of locations the perspective kept on evolving, so did my perception about what required to be done. It evoked no immediate questions, but a vague sign of interest, which made me put across all my thoughts in following sequences.

No clear road ahead, and the refugee influx could ignite unforeseen political crisis; ad hoc assistance to skirmishing would not lead to any strategic breakthrough, could only widen Pakistani reprisals and increase refugee outflow; no 'political solution' would work, would not give any confidence to refugees to return till Pakistani troops were withdrawn, nor the junta would withdraw troops for fear of greater peril; only to a liberated Bangladesh refugees would go back, and to liberate it a large number of freedom fighters needed to be trained and inducted according to a well formulated strategy; Pakistan might disrupt that buildup by a pre-emptive war, in collusion with China making diversionary attacks along India's north-eastern border; only the Soviet Union, because of its huge mobilization on China's border, had a powerful lever to restrain China and fill in India's security gap; to overcome the Soviet apathy towards Bangladesh's independence, an ideological format could be created by floating a national liberation front comprising of AL and two pro-Moscow parties of Bangladesh, CPB and NAP; such unity with a common programme of setting up a political infrastructure could help well co-ordinated attacks deep within the country; and, finally, it was for India to make its armed forces ready to effect a final blow and fulfil the conditions for refugees to go back.

A tiring long canvas, I took quite a bit of time to elaborate, but PNH listened to me without any interruption, and at the end he got up to telephone to someone: 'Professor sa'ab, if you are free, why don't you come over and share pot luck with us, there is somebody from Bangladesh.' P N Dhar, Advisor to the Prime Minister, joined us soon after. But before that PNH asked his first question — would it be acceptable to Awami League to forge unity with other parties even on a minimum programme? No, I answered, the party as a whole had been all along opposed to seeking unity with other parties, and rightly so after they won almost all the seats in the last election. But now as the situation had drastically changed, their views would change too, and in fact, sections of the AL leadership were considering to seek some kind of unity to pursue a programme with other pro-liberation forces, including CPB and NAP, in order to set up secure bases within the country to assist guerilla operations, and, also, to improve the acceptability of the Bangladesh struggle to the Soviet Union.

PNH asked me if he could know who led that group. I mentioned Tajuddin's name, and hastened to add that all I spoke to him a little while ago, were discussed previously with Tajuddin in details, and it was his idea that I should draw your attention to our view on broader geopolitical aspects of the struggle; and that he also wanted to arrange a meeting with you, but meanwhile Daniel's unparallel enthusiasm changed that format somewhat and gave me an opportunity to try out the ideas first and establish references later. Daniel, the extraordinary American scholar friend of Haksar, who was listening all through, could not contain his happiness at this point. Before leaving, Haksar wanted me to postpone my departure by a day and to see him on Tuesday at the South Block.

When I met him at his office on Tuesday, 1 June, he was warm and more communicative, and I felt from the very nature of his talk my references meanwhile had been checked. He wanted to know details about the prospect of floating a multiparty front, and the ground work required to be done in this connection, and said that he would remain interested to know about its progress. Secondly, he said that someone on behalf of the Bangladesh Prime Minister should try to set up direct contact with the Soviet ambassador or a senior embassy official and should maintain regular contact with them to exchange views. He said nothing about the prospective security co-operation agreement with Soviet Union, nor did he dispel our perception about China's possible collusion with Pakistan to derail the liberation war. But by showing interest in promoting a liberation front, to suit Soviet Union's ideological taste, and by advising that regular contacts be started with Soviet embassy officials in India, he gave me an impression that our views were worth considering.

On return I briefed Tajuddin about the strong cross-currents in New Delhi over Bangladesh policy, and the broad understanding that was reached with PNH. Tajuddin said that he would soon be able to start work to promote the national liberation front. Hardly a week after my return, Aruna Asaf Ali, publisher of The Patriot, came to Calcutta and informed me that following a request from PNH, she had made an appointment for us with VI Gurgianov, of Soviet Cultural Centre located at Wood Street in Calcutta, who would receive us whenever we wanted. Tajuddin wanted me to carry on the dialogue. During the very session he was awfully frank in expressing his negative views about viability of the liberation struggle, the political commitment of its leadership for a long-drawn struggle, and India's capacity to sustain it. Despite the tough stance during the first session, the negotiation continued for three more weeks, once every week, mostly on about perspective than policies. He started accepting that something new was emerging and eventually some common ground was identified.

Nothing appeared to have happened in the next five weeks to indicate that developments were taking place along the expected line. The public expectations meanwhile kept on boiling in favour of 'political solution', to be mediated by the US, which received a setback a third week of June, after the disclosures that a number of US ships were sailing towards Pakistan carrying armament spares and components. The hype reached its highest point on the occasion of President Nixon's national security adviser, Dr Kissinger's visit to New Delhi during the first week of July. I received a message around that time from PNH enquiring about the progress made towards formation of the national front. That was the first indication in more than a month that the approach decided upon earlier was still relevant, despite all the interactions between India and the US at various levels. But Tajuddin meanwhile made little progress in floating the proposal of national alliance, since he faced hostile factional campaigns on the advent of AL elected representatives' conference (5 and 6 July) at Siliguri, and he barely succeeded to pacify a faction openly advocating for 'going back to the country to carry on the fight or seek reconciliation with Pakistan, since India had let us down in every respect'.

I went to New Delhi soon after Dr Kissinger's secret trip to China was made public, which created commotion in all circles, and dismay for those who advocated US mediation so far. On 19 July, a little late in the evening, PNH dropped in at Ashok Mitra's house and informed me that 'some thing very positive, along the line we discussed, was going to happen soon'. To be precise, as I barely mentioned the name of Soviet Union, he gave a firm nod. I left for Calcutta the very next day, and Tajuddin planned to start the initiative for the multiparty unity, but only after the security co-operation treaty between India and the Soviet Union was signed.

On 9 August, the Indo-Soviet Treaty for Friendship and Cooperation was signed in New Delhi, which Kissinger subsequently termed as a 'bombshell' in his memoirs. Indeed, the treaty, by agreeing to have joint consultation in the event of a threat from a third party and to take appropriate action to restore peace and security, decisively changed the course of subsequent events. As the reconstruction of history goes on, some writers in recent years play down the threat of collusion perceived by us to the level that the US was using the Pakistani channel to open up to China for its own geopolitical interest. That might well be, but, in addition, there was a darker aspect of that opening too, as Richard Nixon made it clear in his memoirs: "The Chinese played a very cautious role in this period. They had troops poised on the Indian border, but they would not take the risk of coming to the aid of Pakistan by attacking India, because they understandably feared that the Soviet might use this action as an excuse for attacking China. They consequently did nothing". (page 530)

And how much Haksar did to make that strategic treaty a reality?

I have not seen any official papers on that yet, but I can reproduce from my notes on what D P Dhar told two years later. A draft treaty for friendship and co-operation was first proposed by the Soviet Union in the buoyant era of 'Brezhnev doctrine' in 1969, and DP, as India's ambassador in Moscow, had negotiated it for six long months, twice every week on Wednesday and Saturday, before it was finally shelved as both sides failed to resolve their differences. DP was summoned to Delhi in June 1971, and Haksar gave him the brief to reach an agreement on the treaty incorporating the amendments acceptable to the Soviet side but covering the security contingencies India might be facing. PNH followed it up all the way down till it was presented to get the approval of the political affairs committee, a committee of cabinet members, where PNH, P N Dhar and D P Dhar were present just to assist them if required!

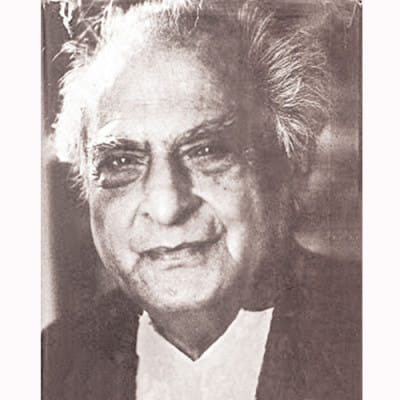

Muyeedul Hasan was a special assistant to Tajuddin Ahmad, the Prime Minister of the Bangladesh Government-in-exile. He is also the author of Muldhara `71 and Upadhara 71, March-April.

The article was originally published in Haksar Memorial Volume 2: Contributions in Remembrance, Edited by Subrata Banerjee, India, 2004.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments