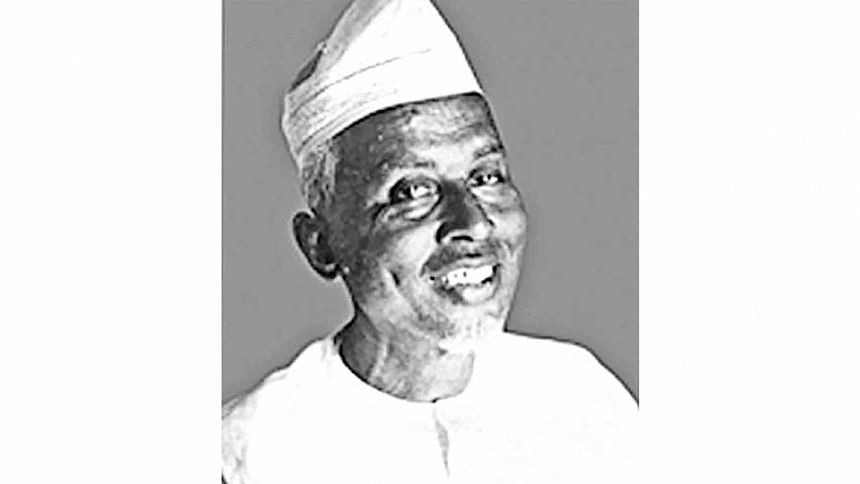

Mahboobul Alam: An early historian of the 1971 war

Following the Liberation War of Bangladesh, the savant Mahboobul Alam (1898-1981) took up the task of writing a comprehensive history of 1971. A septuagenarian, he nonetheless accomplished the task in just a few years. Alam was a great literary Bengali Muslim figure who achieved eminence in the forties in the then undivided Bengal through his powerful novels and stories, which portrayed Muslim life from a new and nuanced lens. This earned him esteem among the Bengali Hindu intelligentsia as well.

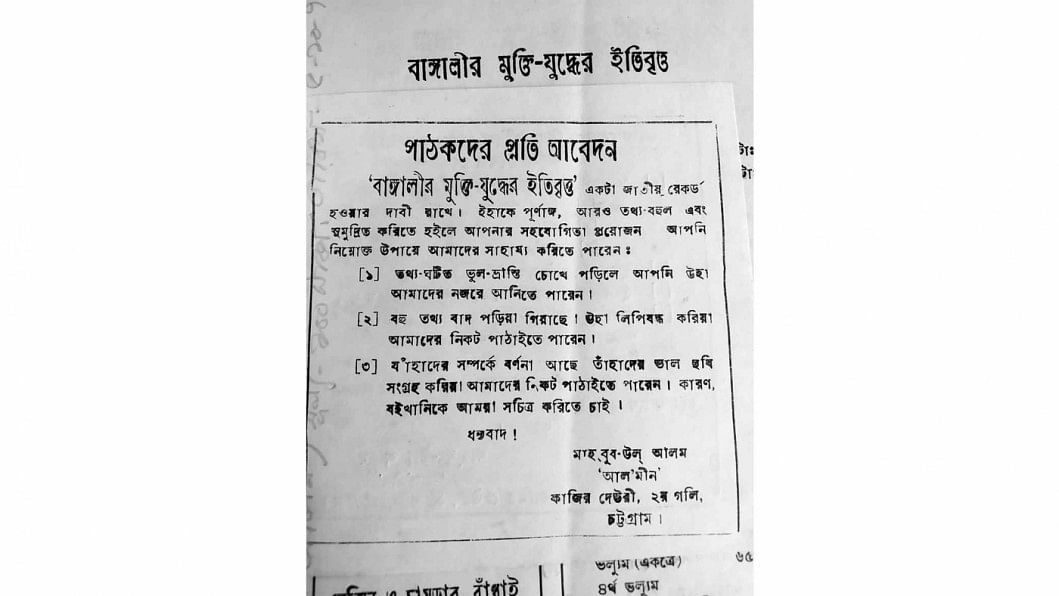

Besides, he joined World War I and penned his experiences about his life as a soldier – now a classic in Bengali war literature. After returning from the war front, he took up a government job as a sub-registrar and started a new career chronicling the history of Chittagong at different periods. He also served a considerable period of time as an editor of Zamana in the Pakistani era. He completed his book, Muktijuddher Itibritto, in three volumes and consolidated them in a single volume in 1976. This book was his last contribution before his death in 1981.

Alam writes the entire three-volume book as an autoethnography. Like flashbacks, he narrated many historical moments, especially the background of the Pakistan movement, to substantiate his arguments. When he finished this book, he was 79 years old. He was driven by a strong conviction that he had a responsibility as a chronicler and a dutiful citizen of this nation to keep the records of the single most important saga of this nation, which is the war of 1971.

Before elaborating on some aspects of this book, it bears mentioning his tremendous efforts in collecting information and sources from primary actors of the war. He conducted many interviews and collected oral histories for this book.

An overwhelming economic disparity between the two wings of Pakistan was pointed out systematically by many perceptive Bengali politicians and economists at that time. Alam also noted such developments, besides highlighting the state-sponsored communal tension and dreadful conditions harboured by the Pakistan state which he witnessed.

In his book, he mentioned that a one-dimensional economic developmental policy had been pursued under the long-time military rule by President Ayub Khan. As a consequence, villagers were almost forced to leave their villages since the rural economy was not offering sufficient opportunities, while some cities were being constructed offering more opportunities both for the educated and labour forces. In addition, Alam mentioned the most heinous crime of Ayub Khan was that he kept a continuous poisonous communal and loathing relationship with India, and his government never attempted to improve this situation. He pointed out that even after the partition of this subcontinent in 1947, seven crore Muslims were staying in India.

Alam argued that in the Pakistan era, he did not find any complexities to being a Bengali and a Pakistani at the same time. He played a role in strengthening friendship between Indian and Pakistani authors and intellectuals from the early days of Pakistan. He assumed that partition of India into the two states took place due to exacerbation of communal problems in various forms. He held that the civil-military axis centred on the West Pakistan wing prevented Pakistan from resolving the communal problem, instead choosing to play the majoritarian card, which doomed Pakistan's future.

Alam argued that Bangladesh made a shaky start after the Liberation War, failing to properly constitute the list of martyrs of 1971. It would have been relatively easy if it had started the process just after the war ended when freedom fighters were coming back from the war front and they could have easily identified their deceased comrades in arms. The entire population could have stepped up efforts in their locality in listing down the names of the martyrs.

As an acute observer and social historian, Alam witnessed many anomalies that took place after and even during the war. His interpretation of the war's aftermath often differed from mainstream narratives. For instance, he argued that those who fought in the frontlines did not get a strong role in the post-liberation state.

National liberation movements are often followed by thwarted desires, disappointments, and frustrations. It has been a common experience in various post-colonial states that after the ousting of colonial rule, the situation does not change as radically as would have been ideal. Buddhadeb Dasgupta, in his famous film Tahader Katha, based on a story by Kamal Kumar Majumder, narrated how a revolutionary got frustrated and ultimately turned insane having observed the post-independent development which did not reflect the hopes and aspirations that he cherished in the colonial time. Alam observed similar processes at work after the victory of 1971. In addition, if we look at the composition of freedom fighters of the war, we would see 70 percent came from the peasant background who did not much say in governance after the war.

In this book, he briefly discussed Awami League's strategy in the non-cooperation movement through March 1971 that finally led to the war. He pointed out that Awami League created maximum pressure upon the Pakistani Junta through their movement, but their preparation for the war was minimal. Thus, the war faced a lot of setbacks from the very beginning due to lack of preparation which should have been taken. Nonetheless, the vehement efforts of East Bengal Regiments and East Pakistan Rifles aborted the ex parte victory of the Pakistani army.

Furthermore, Alam mentioned Sheikh Mujibur Rahman always remained faithful to his principles. He concluded that the historic March 7 speech of Bangabandhu would be resonating for more than 200 years in the history of Bengal.

In sum, the 1971 war remained incomplete in Mahboobul Alam's reckoning. But then again, it is hard to say that any war is accomplished, or that a revolution is permanent.

Priyam Pritim Paul is pursuing his PhD at South Asian University, New Delhi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments