Colonial footprints European architecture and spatiality in Dhaka

The movement of architectural motifs does not merely result in an assemblage of pre-existing forms; rather, it often establishes a new spatial order through their interplay, sometimes even symbolically appropriating land. Most colonial administrators were profoundly influenced by Renaissance sensibilities, particularly in art and architecture. The surviving structures indicate that while the Indo-Saracenic style became an official ideology, it also paved the way for the globally recognized bungalow. These sites of memory do more than just recount European presence; they schematically illustrate how a novel sense of spatiality took root—shaping sociability, commerce, religious practices, and intellectual pursuits

Site of Sociability: Northbrook Hall

Alongside the advent of modern railways, medical systems, and educational institutions, European establishments disrupted the existing land organization, imposing a new sense of place. By embedding a modern surveillance state that pervaded all aspects of life, they redefined social interactions, leading to the emergence of town halls, theaters, cinemas, and public libraries

One such significant structure is Northbrook Hall, an imposing edifice on the banks of the Buriganga River in Old Dhaka. Originally designed as a town hall, it was named after Lord Northbrook, the Viceroy of India, and was established between 1872 and 1886. Over time, it was repurposed as a clubhouse and public library, fostering sociability among the city's residents

Adhering to the dominant Indo-Saracenic architectural style, which fused Mughal and European Renaissance elements, Northbrook Hall stands as a striking testament to the empire's influence. Renowned art historian A.H. Dani describes its spatial essence as follows:

"The semi-circular horseshoe arches, the projected bay containing the entrance on the north, the four octagonal minarets at the northern salient, the ornamented parapet, and the towering pinnacle above distinguish its Muslim features. The entrance bay has a trefoil arch on the outer face with a floral pattern at the spandrels and spirally fluted plaster supports below, which are highly ornamental."

Additionally, the building's deep red hue, coupled with its tiered roofs, pinnacles, and parapets, creates a visually striking panorama from the river esplanade. Notably, Northbrook Hall, also known as Lalkuthi, reflects its erstwhile commercial legacy, serving both as a garden house and a warehouse. Stepping into Northbrook Hall transports one into the refined world of 19th-century gentlemen and their leisurely pursuits

The Coevalness of Commerce & Romance: Nimtali Gate

The expanding European presence in Bengal was closely intertwined with commercial ventures. As a result, Kuthi houses began proliferating along the river routes leading to the sea. With a significant concentration in Rajshahi, Jessore, and other parts of Bengal, Kuthi houses evolved into garden residences—the dwellings of the Shahebs, sometimes doubling as pleasure houses, apart from their primary function as warehouses for indigo and silk production

Regarding its architectural layout and spatial organization, A.B.M. Hussain provides the following description:

"It seems that the word was originally applied to the factory in general, consisting of the factor's residence, attached warehouses, and production centers. However, over time, it became limited to a single house, occasionally two-storied, with all necessary facilities contained within."

A notable example is Nimtali Kuthi, which embodies Bengal's enduring riverine trade network and its commercial infrastructure. Established by Naib Nazim Jasrat Khan, the Kuthi was demarcated by Nimtali Gate, initially serving as a storehouse

Europe's Holy Presence: Holy Rosary Church of Tejgaon

It is often observed that wherever European business tycoons established themselves, Christian missionaries soon followed, raising the flag of the Holy Cross. Above all, European expansion was driven by the three Gs—gold, glory, and God. Soon after arriving in Calicut, missionaries extended their reach to the alluvial plains of Bengal, with Chattogram, Dhaka, and Hooghly among the earliest witnesses to their presence. The deltaic terrain of Bengal, crisscrossed by enormous rivers, gave rise to a unique form of religious architecture, blending local and European elements. Incorporating arches, turrets, cornices, and flat plastered surfaces adorned with geometric and panel decorations, these churches left a lasting imprint on Bengal's architectural landscape

A prime example of this legacy is the Holy Rosary Church in Tejgaon. Originally built in 1677, it underwent renovations in 1714 and again in 2000, yet it continues to stand as a glowing testament to history. Structurally, it is divided into two distinct sections: eastern and western. The differences in roofing styles clearly indicate that the eastern section was a later addition by the Augustinians, adjacent to the pre-existing western section, which is smaller in size and features a robust surki wall measuring 48 inches thick

Schooling for Empire: St Gregory's High School

With the expansion of European influence in Bengal, colonial authorities were equally committed to bringing the native population under their so-called civilizing mission. However, the establishment of educational institutions was less about enlightening the local populace and more about creating a skilled administrative class to facilitate colonial governance

One of the earliest schools in British India, St. Gregory's High School, has served the nation since its founding in 1887 by the Benedictines. Initially, the school provided education up to Class Eight and operated as a coeducational institution. However, the girls' section was later relocated to a nearby site

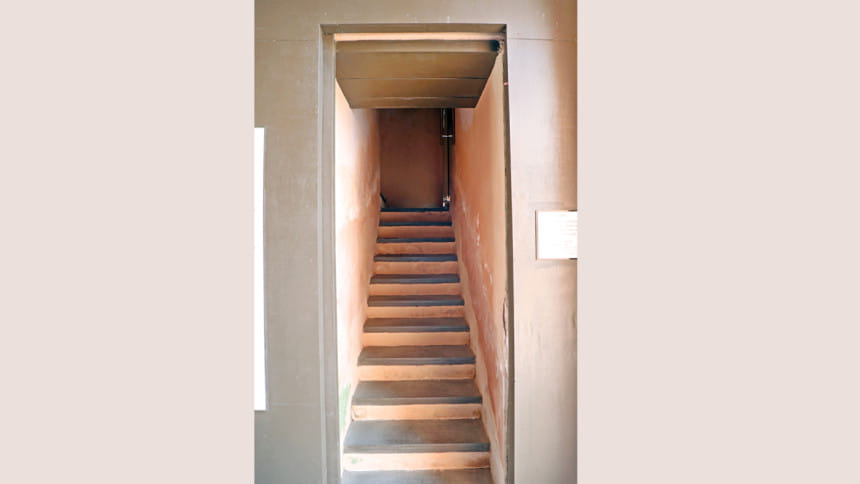

Originally situated adjacent to the church, the school complex features an irregular shape, though it is predominantly rectangular. Large open spaces extend along the southern and eastern sides of the building. The front façade, adorned with Gothic-style decorations, creates a striking visual impact, drawing the attention of passersby. In contrast, the other façades remain relatively unembellished. With its orientation, circulation, spatial organization, lighting, and ventilation, the school's architectural form and construction techniques evoke the legacy of Kuthi architecture. The architectural styles of schools across Bengal serve as a testament to the once-prominent Kuthi establishments

Ultimately, it can be said that the school did not merely produce colonial subjects—it endowed its students with a new soul

A Fleeting Encounter with Empire

Standing at these sites of memory, one experiences a sense of Europeanness, both temporally and spatially. These spaces act as reservoirs of stories—not all of them pleasant. The roots and routes of empire can be traced in every nook and corner. Being in the vicinity of these sites offers a fleeting yet intense encounter—much like a one-night stand with Europe

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments