‘The true essence of a city lies in its streets and public spaces where life unfolds organically’

A conversation with Saiqa Iqbal Meghna, internationally acclaimed architect recognised by TIME's World's Greatest Places, Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, BRAC University, and Director & Partner at Studio Morphogenesis Ltd.

The Daily Star (TDS): What is the current scenario of living space and public spaces in Bangladesh, particularly mega cities such as Dhaka and Chattogram and other developing divisional cities?

Saiqa Iqbal Meghna (SIM): Planning and quality—both of living spaces and public realms—are the keystones of a vibrant city. A city, after all, is more than just a collection of buildings; it's a dynamic ecosystem where people, commerce, culture, and ideas converge. It thrives when it manages to balance planned structures with those spontaneous, serendipitous moments where unanticipated joys emerge from human connection.

When I consider a mega city like Dhaka, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, the stakes in urban design soar dramatically. Rapid population growth puts immense pressure on already scarce resources, deepening socio-economic divides and intensifying environmental concerns. Over time, we have seen miserable declines in the quality of both living spaces and public realms in Dhaka. Despite contemporary architects creating some truly commendable apartment projects, what often unfolds on a city scale is an archipelago of stand-alone structures with little regard for shared spaces. The setback areas, usually left unused by boundary walls, miss the potential to serve as landscaped connections that could weave neighborhoods together. This trend—moving away from humble, integrated housing designs with common facilities like open fields and community parks—is contradictory to the notion of sustainable living solutions in a growing mega city.

As a daily commuter journeying from Badda to Dhanmondi, I experience the infamous Dhaka traffic firsthand—perhaps one of the worst congestions in the world. It is disheartening that proper pedestrian pathways and effective public transport solutions remain elusive. Instead, we lean ever more on private modes of transport, worsening the overall condition and impacting the quality of life for many.

The scarcity of well-maintained public spaces—parks, fields, plazas—as well as the lack of proper footpaths has a tangible effect on the well-being of the citizens. It is essential that we start planning both the private and public realms in harmony with the local landscape and ecology. In this regard, innovative ideas like the "sponge city" concept, championed by Kongjian Yu in China, offer inspiring examples of how large-scale ecological urban design can forge a symbiotic bond between the natural and the built environment.

The true essence of a city lies in its streets and public spaces where life unfolds organically. Imagine walking through a city where every turn, every building, every public square pulses with vitality and purpose. There's more to urban life than just physical structures where poetic moments would occur spontaneously. This is where Italo Calvino's poetic vision of the city as a narrative comes into play. Our urban landscapes must be flexible canvases, allowing unforeseen moments to unfold—whether it's an impromptu street performance, a vibrant mural revealing hidden stories, or a community garden emerging in a vacant lot.

TDS: Could you share your journey as an architect, highlighting the inspiration that shaped your design philosophy? How do you incorporate your design philosophy into your work?

SIM: For me, designing is a creative act that blends an intuitive sense of beauty with a rich tapestry of embodied experiences gathered over time. Our surroundings, people, and memories contribute to shaping a character—a deep, inherent quality that must be nourished and ultimately manifested through creative expression. Each phase of life adds a new layer, nurturing the vision that guides my work as an architect.

I've always felt an intense attraction to 'people' of strong ideological standing and to 'places' with a profound character—whether it's the quiet charm of old cities or the raw beauty of natural landscapes. Over the years, I've been fortunate to encounter environments and individuals that serve as reservoirs of inspiration, imbuing my design philosophy with a sense of beauty born from pure purpose and humanist ideology.

Reflecting on my childhood, I vividly remember the shared wall housing along Salimullah Road, where I grew up with its layered courtyards, terraces, and interconnected roofscapes. This was an era just before profit-driven apartment culture took hold, a time when ample sunlight, fresh air, and natural ventilation were just as essential as the functional rooms arranged on a compact plot. I recall a large verandah facing the street, graced by a three-storied high madhobilota; it was a dreamlike space where the morning would heralded by the sound of a record player and the sight of an artist immersed in watercolor on the open verandah. On full-moon summer nights, my father would even sleep in that very verandah, accompanied by the songs of Suchitra Mitra or Feroza Begum from his cherished collection of rare records. His multifaceted passions—as an artist, music lover, gardener, and lifelong communist—were deeply infused in my creative DNA.

Both my parents, unlike many middle-class households, were devoted to nurturing our creative potential. They wanted at least one of their daughters would pursue singing professionally, which none of us eventually did. My father often took us to Tagore song lessons at Dhanmondi, right next to the home of Begum Sufia Kamal, and afterward we would visit the poet's residence—a small, south-facing house nestled in a garden with a fishpond and a graceful fountain. A humble place with the presence of a humble yet immensely powerful persona of a poet– a unique ambience that must have cast a profound impact on a child who was observant and eager to learn.

My journey as an architecture student started at the vibrant atmosphere at BUET, where the architecture faculty—designed by Richard Vrooman—boasted an open plinth that linked the south and north courts, long corridors with iconic louvers, and grand staircases that celebrated modern design attuned to our monsoon climate. The dynamic inputs of our teachers and the collaborative spirit among peers turned every discussion—from rigorous design debates to casual adda—into a valuable lesson in creative exploration.

I went to Barcelona to pursue Masters of Advance Architecture degree. It was a conscious decision to select the best possible city in the world where I could explore more beyond the academic curriculum. Barcelona's meticulously articulated public spaces, lively pedestrian ramblas, and the seamless coexistence of historic and modern architecture infused the young architecture student with boundless inspiration and a profound sense of creative possibility. Bathed in the beautiful Mediterranean light and enriched by a tapestry of cultural encounters, the city became my constant muse.

Few years later, I was offered a scholarship to attend the Glenn Murcutt International Master Class in the Shoalhaven river valley. It was a significant transformative phase for me. Staying at the Arthur Byod Center—a lightweight pavilion form by Pritzker winner Glenn Murcutt—amidst the rolling green valley where kangaroos and wombats roamed, was nothing short of magical. Among my mentors, Richard Leplastrier stood out like a grand banyan tree, teaching me to nurture a longing for architecture that is both "deep and wide"—a beauty of pure purpose that continually fuels my creative drive.

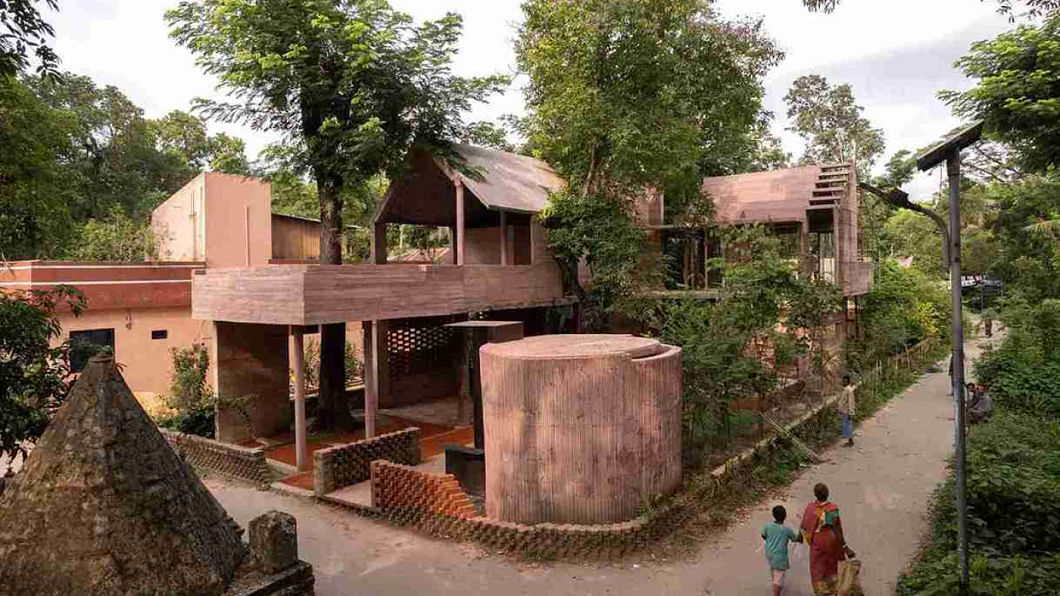

After years, I got another opportunity to experience closely an almost hermetic place, an otherworldly subterranean architecture located near the unique braided river system of Brahmaputra- Jamuna. 'Where Rivers Rule' was a workshop by contemporary master architect Kashef Chowdhury. What made the experience truly remarkable for me was the close encounter with an architect immersed in a deep search for absolute architecture.

These accumulated experiences—extraordinary places, inspiring people, and unforgettable moments—have profoundly informed my design philosophy. Today, architecture is for me an endless pursuit of an unattainable beauty, a continuous search for a vastness that transcends mere functionality. I feel an increasing responsibility to design spaces that cast an enduring "deep and wide" impression, elevating the human experience beyond conventional boundaries.

In my work, I strive to translate these values by exploring form, geometry, and tactile surfaces—using locally sourced, cost-effective materials in a limited palette. I try to evoke the poetic perpetuity of living in the monsoon delta, creating spaces that honor both flexibility and openness, and ultimately, that celebrate the intimate dialogue between people and their environment.

TDS: How do you incorporate principles of inclusivity in your architectural designs to ensure public spaces are accessible and welcoming to diverse communities?

SIM: To answer your question, I would like to start with the profound words of Louis I. Kahn: "A city is the place of availabilities. It is the place where a small boy, as he walks through it, may see something that will tell him what he wants to do his whole life."

For me, Kahn's words encapsulate the essence of what architecture should be—an ever-present source of inspiration. This philosophy drives my work, especially within the challenging context of Dhaka city, where volatile socio-political climates, minimal resources, budget constraints, and a diminishing pool of skilled masons put me into challenge to balance the poetic with the pragmatic. I continuously try to pursue impactful architecture at the intersection of inclusivity and ecology, infusing local, global, and digital crafts and material processes.

In my practice, I approach public spaces as "landscape events" that unfold through choreographed encounters. Growing up, my experiences ranged from the small neighborhood shops scattered along Salimullah Road to the grandeur of the National Parliament—where mornings were spent on leisurely walks and afternoons filled with play. The majestic, monolithic form of the parliament building rising gracefully from the water left an indelible mark on my imagination. My early memories, enriched by weekends at my aunt's home located inside the red brick MP Hostel, introduced me to the masterful interplay of solids and voids, light and no light—a dialogue between monumental and intimate spaces that deeply resonates with the way I envision public scale. Unknowingly as a curious child I have absorbed my first lessons of architecture through Louis I Kahn.

Complementing these early inspirations, my frequent visits to spaces like Charukola—designed by Muzharul Islam —helped me appreciate architecture as a tool for social transformation. Spending time with my artist father at the Faculty of Fine Arts, a masterpiece of regional modernism, further instilled in me a sensitivity toward public spaces that blend seamlessly with nature. These experiences taught me the value of creating environments that are at once open and inviting yet possess a dignified sense of enclosure.

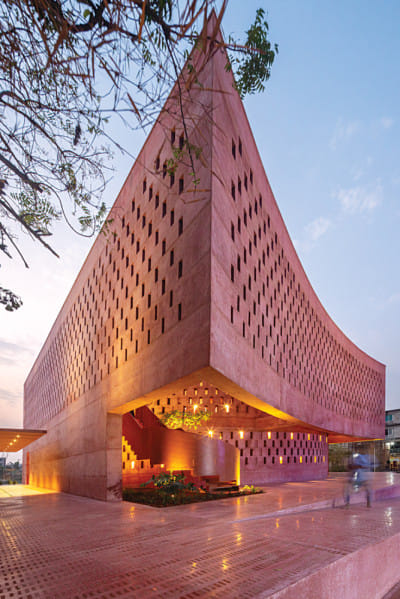

Now even when I introspect my residential projects, I find a spontaneous manifestation of a certain layer of publicness. Take, for instance, the recently completed Faridpur Residence, where the open ground floor and the green front yard invite the neighbors to pause during their daily routines. The design features a carefully orchestrated sequence of public and semi-public layers—with expansive terraces, large vaulted shades, and lush lawns crowned by a majestic lily pond—which together assert a grand yet friendly presence in the neighborhood. Similarly, our under-construction residence in Chittagong echoes this sense of inclusivity by dedicating the ground floor for public use through locating a community Mandap and engaging courtyards leading to a vibrant vegetable garden and orchard that are cultivated by the community women.

In a country rich with poetic seasonal variations, monsoon rains, flowing rivers, and centuries-old vernacular methods, I find it essential to explore the potential of local crafts and building traditions alongside a global language of architecture. Every project I undertake is a dialogue with nature—a dialogue that creates contemporary spaces deeply rooted in the local context. To ensure inclusivity, my public projects incorporate elaborate ramped entrances, grand steps that turn as seating galleries, tactile pigmented paving, and carefully crafted material selections using cost-effective, local resources. These elements not only enhance accessibility but also forge a tangible connection between community, culture, and the built environment.

In essence, I try to create living, breathing spaces that nurture a city's soul—places where every individual, from a curious child to a thoughtful elder, feels seen, respected, and connected.

TDS: Being a woman in a predominantly male-dominated sector, how do you assess the challenges and opportunities for women architects in Bangladesh, reflecting on your own journey as well as that of your female peers?

SIM: As a woman in architecture who feels obligated to be consciously inclusive, I take on the responsibility of providing common ground for people of all social classes, genders, ages, and races. When you refer to "being a woman in a predominantly male-dominated sector," I prefer to think of it as being a woman in a predominantly male-dominated society—because the challenges we face extend beyond just the field of architecture. From our early days as girls to our growth into women, we encounter extra obstacles and challenges that, in turn, make us more sensitive and observant. I personally think this sensitivity becomes even more profound with motherhood; the immense journey of being a mother has made me more resilient, sensitive, and responsible as an architect, a transformation that I believe has significantly enriched my approach towards design. I am increasingly committed to socially driven and environmentally responsive design for our future generation.

If I particularly talk about architecture as a profession, it is clear that it demands utmost focus, often going beyond a 9-to-5 schedule. In a society dominated by male perspectives, many women find it difficult to pursue this career. I've met many brilliant female architecture students—be they peers, seniors, or juniors from BUET, or even my own students—some of whom, despite their outstanding results, ended up unable to continue as practicing architects. Still, we have inspiring examples like Marina Tabassum, who stands not only as a powerful architect in our context but also as a global icon through her extraordinarily impactful work and intelligent practice. She has been a true mentor for me. Whenever I feel an urge to gather myself I visit her at her office, a true architect's studio full of finely crafted wood and metal models.

I strongly believe that women architects in Bangladesh have the opportunity to harness their unique sensitivity and resilience—shaped by diverse life experiences—to drive socially committed and environmentally responsive design.

TDS: Balancing your roles as both an academician and a practicing architect, what advice would you offer to young professionals and students entering the field of architecture today?

SIM: Embrace your power to transform spaces and societies. Your work has the potential to break down entrenched barriers—whether they manifest in spatial design, aesthetic norms, formal structures, historical narratives, political ideals, or societal norms. Connect yourself with creative people from diversified background. With today's cutting-edge technology, innovative materials, and wide opportunities of collaborations, you're uniquely equipped to pioneer a new era in architecture.

Embrace the atmospheric world around you. Learn to sense and interpret the interplay of sunlight and raindrops, and attune yourself to the subtle changes of nature. Look intently—not just at what is visibly present but also at the silent gaps and unspoken absences. As a young architect, make it a daily practice to sketch more as it helps you to capture the transient beauty of your surroundings; listen deeply to music, for its rhythms open your mind to new perspectives; and write consistently, letting your reflections and observations crystallize into inspiration. Read widely, journey far, and let your experiences of the world's diverse beauty inform your creative vision.

Cultivate your tenderness and sensitivity. These qualities form a deep well of strength that architecture not only benefits from but truly needs. The world teems with unexplored narratives, overlooked voices, and uncharted realms waiting for your attention. Ultimately, never stop dreaming for a better world; let it be the spark that fuels your journey in architecture.

The interview was taken by Saudia Afrin.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments