The song remains the same

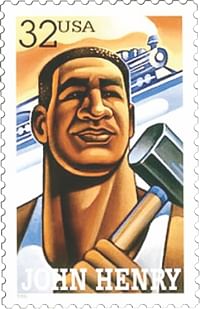

He's a hero to Woody Guthrie, a warning to Mississippi John Hurt, an inspiration to the chain gang. From verse-to-verse, generation-to-generation, the story changes to suit the singer. The name and steel-driving solitude stay the same. He is John Henry, the man who "Died with a hammer in his hand”, who knew “a man ain't nothing but a man”.

The ballad of John Henry, with which we are so familiar, tells a basic story, in spite of its seemingly infinite number of verses. Often the ballad begins with a view of John Henry as a baby on his mother's or father's knee, a baby who notes that either hammer, steel or the Big Bend tunnel itself will eventually cause his death. Then come the preliminaries for the big contest between John Henry and the steam drill. Then comes the contest, which is usually followed by verses about John Henry's death: "He laid down his hammer and he died." And these verses in turn are usually followed by passages about John Henry's woman, Mary Magdalene, Polly Ann, Julia Ann, Mary Ann, or in one version, Paul E Ann. Often these latter verses are mingled with descriptions of the funeral and reactions of other women:

"When the women in the West heard of John Henry's death, they could not stay at home...."

But the popularity of “John Henry” -- part of American culture since the 1870's -- is not only due to the story it tells but how it tells it.

This tune is the quintessential American melody, full of pulse and rhythm, going back and forth between the high and low notes, from a scream to a whisper… Among the many different instruments used for singing “John Henry”, the guitar used with a bottleneck to slide on the strings is the most appropriate (and one of the most widespread among blues guitarist) to render the “blue” notes and the wailing quality of the melody.

It arose from the same African-American culture that produced blues, and has been performed by many important blues players, including Big Bill Broonzy and Leadbelly.

As far as authenticity, there's really no better moment than that recorded in 1947 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman. In the melodies of the ballad, Alan Lomax writes, "The African slave, transformed into steel-driving John Henry, put the Bill of Rights into one phrase: A man ain't nothing but a man."

It's hard to tell just how many ballads, jazz riffs and blues songs made the trip North during the urban migration of the early 20th Century. "John Henry" traveled with Big Bill Broonzy, who was born in Mississippi in 1893 and settled in Chicago by the late 20s.

In 1931, Pete Seeger learnt the song from a painter. He would record it in the 50s.

Woody Guthrie was the bridge between the hipster bohemia of the '50s and the more mainstream folk revival that spread across college campuses in the 60s. Not surprisingly, Guthrie remembers "John Henry" as a working-class hero. Guthrie isn't sure where he's from -- "Some said he's born down in Texas," he sings, "some said he's born up in Maine. I just said he was a Louisiana man" -- but there's no question where he ended up: Leader of a steel-driving chain gang.

Harry Belafonte recorded his first album “Mark Twain and Other Folk Favorites” in 1954. It was a collection of American folk songs, including a rendition of “John Henry.”

John Henry also is part of oral tradition of “hammer songs”, songs timed to the beat of a hammer or axe. In 1959, historian Alan Lomax was traveling through the South, making recordings of local and indigenous music. He recorded Mississippi prisoner Ed Young, singing “John Henry” while chopping wood, the lyrics timed to the swing of his axe. This is probably more what the song sounded like in the 1870s.

Then there is Johnny Cash's version of the ballad, "The Legend of John Henry's Hammer."

And the legacy continues. Bruce Springsteen in his 2006 album “We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions,” covers the song in the style of Pete Seeger.

Source: lookandlearn.com, kplu.org, ibiblio.org, work of Geoff Edgers

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments