STORY OF THE BANGLA PRESS

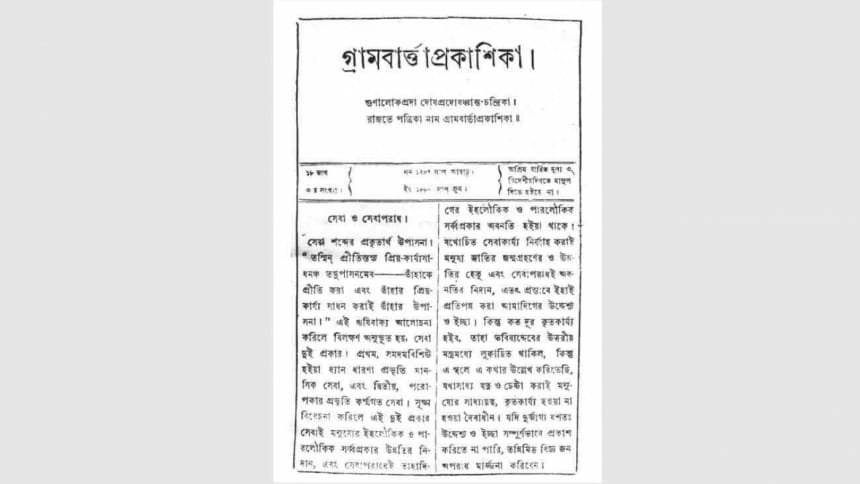

A teacher of a small village was so overwhelmed by the atrocities of the landowners or zamindars of colonial India that he decided to write something in protest. A former employee of a British-owned indigo production factory, he was a first-hand witness of the cruelties against the workers who gave their sweat and blood to only be further exploited by the zamindars and the British Raj. With the help of a loan and his savings, he founded his own publication house in Komarkhali, Kushtia in 1863, as an act of revolution against this oppression. Kangal Harinath Majumdar could thus be called the first investigative reporter of the subcontinent with Gram Barta Prokashita, a Bangla weekly that aimed to generate public awareness regarding the veiled tyranny of those in power.

While Gram Barta Prokashita can be heralded as the first Bangla language newspaper that directly attacked the imperialists and the zamindars, it was far from being the first newspaper or even the first Bangla newspaper in the subcontinent. How exactly then did the ordinary people get the information that the people of today consider their right by law?

A Long, long time ago, the dissemination of information was a privilege solely reserved by the ruling class. Only the news deemed most important would be streamed down to the masses through the help of a messenger and a drum. Ordinary people mostly depended on hearsay and rumours to, ironically, get a truer picture of the political decisions being taken on their behalf by the sovereign powers of the state.

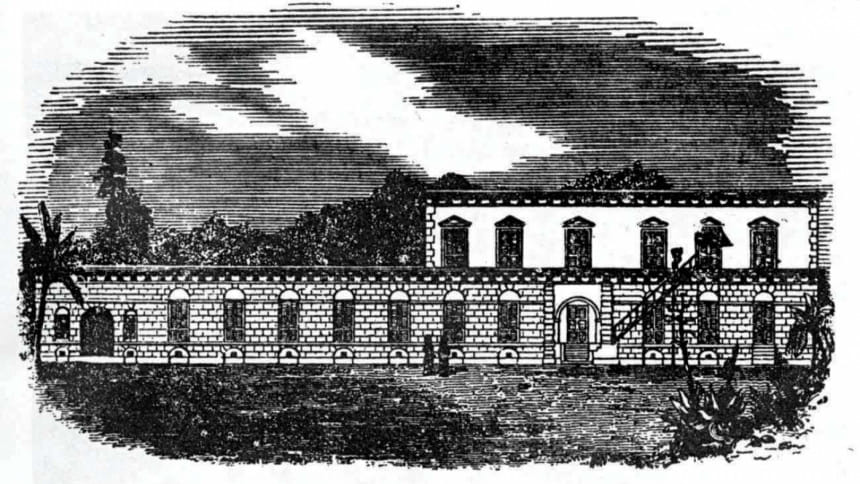

In undivided India, the press began in Calcutta in 1780 to satisfy the needs of the colonials and their cohorts. By the turn of the century, there were a dozen or so periodicals with several hundred subscribers among the European residents of India. The first journal, Hicky's Bengal Gazette, began publication in 1780 and was owned by the Irishman Jame Augustus Hicky who came to India as a surgeon's mate. According to Partha Chatterjee's book 'The Black Hole of the Empire', the weekly English language Gazette initially started as a journal where readers could “get information on various commodity prices in the Calcutta markets, sales and auctions, the arrival and departure of ships as well as fires, thefts and accidents in the city.” It was only when he tried to “liven” his weekly by printing news about the goings-on of the senior officials of the East India Company that he got into trouble with the government. He then went on to incur the wrath of the British Empire by printing stories of bestiality and other vile crimes by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Elijah Impey, and the Governor-general Hastings.

It's little surprise that the imperial government eventually seized Hickey's printing types in 1781 after he was imprisoned against a libel charge by Hastings. After his release from prison, Hickey lived the rest of his life in extreme poverty and died on board a ship to China and was buried at sea. We can't help but note with irony that the editor and publisher of the first printed newspaper of British India was forced to suffer such a fate.

While it's true that the English newspapers inspired the birth of Bangla language newspapers in the region, the difference lied in the intrinsic goals of the Bangla newspapers. English newspapers in Calcutta were a means of entertainment and profit whereas Bangla newspapers aimed for cultural enhancement and to inform and educate the privileged class.

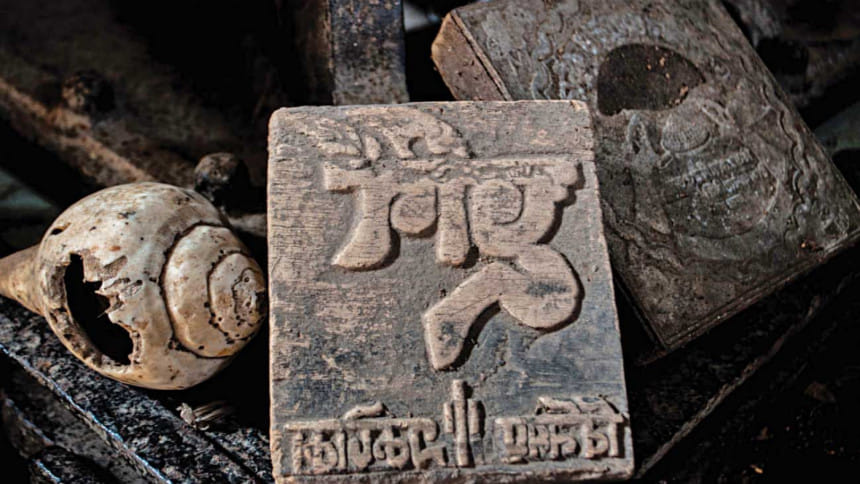

The Bangla alphabet did not exist for print in any publication house until 1778. The Serampore Missionary Press first invented a method through which they created a frame for the Bangla alphabet and formed the different letters by using molten iron. This initiative saw the birth of Bangla publications in the region.

“With the introduction of Bangla alphabets in print, more and more locals of the region began to publish their own newspapers. This was a way of expressing their love for their native land while also providing a voice that was uniquely indigenous to the native populace of the region,” says Professor Sakhawat Ali Khan of the Mass Communication and Journalism department of Dhaka University.

The first Bangla language newspapers, Bengal Gazette and Shomachar Dorpon, published in 1818, were weeklies that were basically published for the entertainment of the elite class of Calcutta. Within the span of five years, a tide of Bangla language newspapers swept the nation.

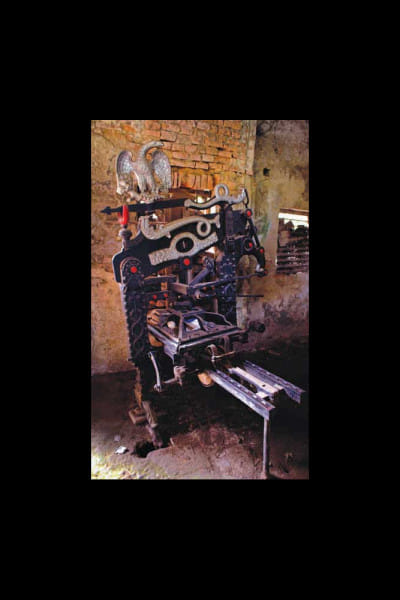

The news publications of the 19th century were printed in hand-driven press machines. The alphabets would be arranged in a frame and then printed on paper. It would take hours for the ink to dry and probably a day to print a small publication. Four workers were required to print a single page; one person would arrange the alphabets in the correct form in a dais, another would place single pages on the dais and apply pressure on the press machine to print the letters, another person would dry the pages after they were ready while someone else would bind them to form a whole publication. It's difficult to even imagine such an arduous process in our digital age.

The newspapers that were published before the 20th century had an open-sentence structure, very unlike the publications of modern times. There was no space for punctuation marks, leading to long, run-on sentences that didn't seem to end. The original form of Bangla, or sadhubasha, was the preferred language of printed publications until the beginning years of the 20th century. The Bangla language was structured further after the publication of Raja Ram Mohan Roy's 'Grammar of the Bengali Language' in 1832 and this was evidenced in the newspapers printed at that time.

Several weeklies and journals in Bangla would be published and most of them were so critical of the British Raj that the government was forced to issue a regulation in 1823. Popularly known as the Adam's Gagging Act, according to this regulation, no news publication could be published without acquiring a license from the Governor General of India. This allowed the British government to choose which newspapers were to be published while also retaining the right to shut down any news publication house whenever they deemed it fit. Even today, you'll see information such as the editor and publisher's name, the address of the publication house and other details on the last page of any newspaper – a remnant of the days of the Adam's Gagging Act.

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, another Gagging Act, which sought to regulate the establishing of printing presses, was passed. The Act held that no printed material could challenge the motives of the British Raj. As is the norm, the act did nothing to supress nationalist sentiments, and thus a more forcible law, the Vernacular Press Act was passed. The Act made it mandatory for every vernacular news publication to submit the proof sheets of their issues before publication to the police for scrutiny. The police were to determine what would be considered as seditious news rather than the judiciary. The publishers found guilty of sedition would be fined and arrested and could not seek redress in a court of law. Interestingly, Sisir Kumar Ghose, the editor of Amrita Bazar Patrika, which was a newspaper that stood against the British Empire by being a voice for the elite, was approached by Sir Ashley Eden, an official of British India, who offered to contribute to his paper regularly and give him some protection from the press act if he gave him final editorial approval. Ghose famously refused the proposal, stating that there “ought to be at least one honest journalist in the land.” The newspaper was forced to turn its content to English from Bangla overnight so that it could continue with its publications despite the existence of the Vernacular Press Act.

The national conscience was so influenced by the Indian Rebellion of 1857 that 87 vernacular newspapers were published from then till 1870. Kangal Harinath's Gram Barta Prokashika is probably the most noteworthy amongst all of them for its fearless presentation of information to the ordinary people. For the first time a newspaper that consisted of soft news segments like literature, poetry and philosophy alongside hard news, was printed for ordinary people instead of the elites or the British government. Interestingly, Mir Mosharraf Hossain, the first novelist to emerge from the Muslim society of Bengal, who penned the famous novel Bishad Sindhu, began his literary career at Gram Barta Prokashika as a correspondent.

“The zamindars of the region had tried to shut down Harinath's publication house by force a couple of times. The celebrated baul, Lalon fakir and his disciples came to his aid to prevent the henchmen of the zamindars from wreaking further violence on his house,” says Ashok Majumdar, a descendent of Kangal Harinath.

In the beginning of the 20th century, two major political parties, National Congress and Muslim League were formed. This led to the publication of newspapers based on political ideologies replacing the core need for preserving empirical and social values practiced by vernacular newspapers of the 19th century. The partition of Bengal, the First World War and the emergence of socialism in the Soviet Union influenced the news publications of the region. Celebrated poet Nazrul Islam and Muzaffar Ahmad published the Daily Nabajug, which presented a reflection of socialist ideologies along with the demand for an independent India.

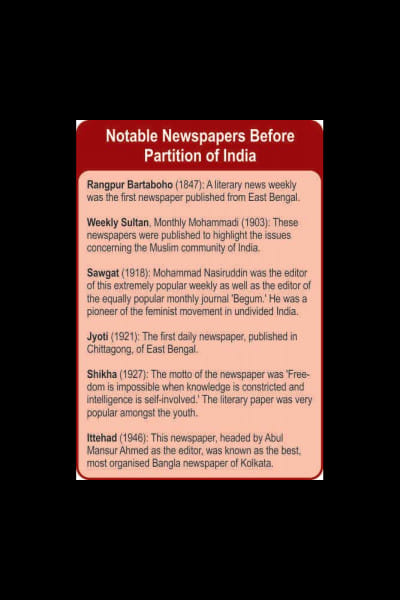

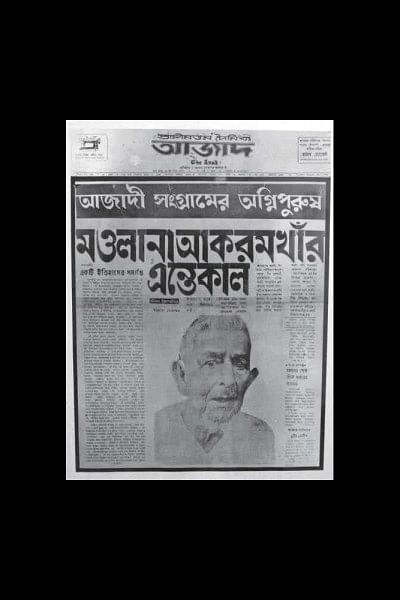

When Sher-e-Bangla A K Fazlul Haq became the Prime Minister of Bengal in 1935, he noticed that he was lagging behind in the political front as he didn't have any newspaper that could back his political career. With the help of Maulana Akram Khan, who served as the editor, he published The Azad in 1936, which helped him gain a firm standing and quick following amongst the people.

“The Azad quickly superseded the popularity of other dailies amongst readers because of its courageous editorials and practice of modern journalism. At one point when someone would say that he/she read the newspaper, they were referring to The Azad,” says Sakhawat Ali Khan.

The Language Movement of then East Pakistan in 1952 further strengthened the consciousness of the Bangla speaking population of Pakistan to recognise spoken and written Bangla as a state language of the then Dominion of Pakistan. We all know that on February 21, 1952, several students and political activists were killed during protests at the campus of Dhaka University. Bangla language newspapers such as The Azad and The Dainik Sangbad marked the killings with evocative articles, ignoring the threats and risks posed by the Pakistani occupation forces. Every newspaper of the then East Pakistan carried the same editorial, condemning the killings and criticising the Pakistani government for its brutal murder of innocents. On the very night of February 21, 1952, the poet Mahbubul Alam wrote his legendary poem Kadte Ashini, Fashir Dabi Niye Eshechi,' which was published by Engineer Mohammad Abdul Khalique from Kohinoor Electric Press the very next day.

Even though The Azad was a Muslim League based paper, they published week-long investigative reports on the incident. Eventually, The Azad became the main source of collecting the historical incidents of that time.

The still popular newspaper Ittefaq was first published in 1953 under the leadership of editor Manik Miah. This galvanized the nationalist movement and was also responsible to enhance the popularity of Awami League, one of the leading political parties of East Pakistan. The Ittefaq was targeted by the Pakistani regime several times for its intensive coverage of the Student Movement in 1962, the movement against communal riots of 1964, the six-point programme in 1966 and the mass movement of 1969. It was also shut down for a period by the government for supporting the freedom movement while its editor was arrested.

During the Pakistani regime, there was constant surveillance and censorship of the press and all publications in general. After the language movement of 1952, the Pakistani occupation force began publishing newspapers with the express aim of spreading its own agenda. Despite these attempts, the regular people, freedom fighters and the intellectuals of the region published daily newspapers and periodicals on their own initiative.

During the war from March 25 to 31 the three leading newspapers, Dainik Ittefaq, The People and Sangbad published from Dhaka, were burnt down by the Pakistani army in course of their operation.

Hasina Ahmed a veteran researcher and the Associate Editor of “The Journal of Social Studies” believes that there was an urgent need for newspaper publications, and so the ordinary people and freedom fighters took the initiative to set up secret newspaper houses in the country. “1971 Muktijuddher Potropotrika,” a research book written by Hasina Ahmed, recounts that with the help of freedom fighters, journalists brought out the latest information about the war and made public unity against Pakistani militants. At the time almost 65 newspapers were published.

In the early sixties, the military government of Ayub Khan enforced a law called the Press and Publications Ordinance to keep the newspapers under government's control. The salient features had been used drastically to control information. Journalists were bound to revise news content by the district magistrate, similar to the Vernacular Press Act of colonial Britain. According to Hasina Ahmed, a military press advice authorized in July reads that the newspapers could not use words like-- Bangladesh, ganabahini, muktijoddha/muktifouz and joy Bangla.

The Pakistani occupiers took over the daily national newspapers but a few were running independently denying the dictator's censorship. And a few were running from Mujibnagar and different places in India, including Calcutta.

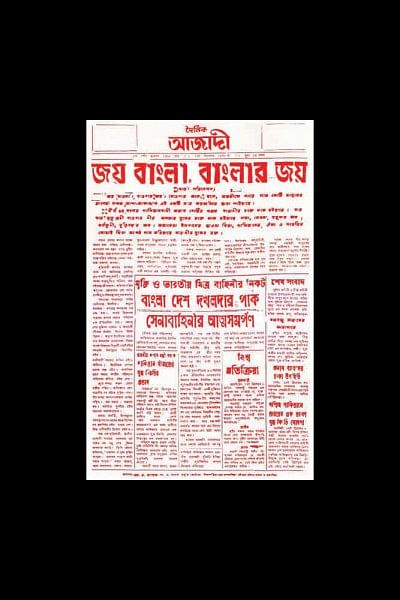

One of the most popular newspapers of that time was The Daily Ajadi, published from Chittagong and considered as one of the first newspapers to be published on December 17, 1971, after Bangladesh's independence. It wasn't easy to print such newspapers at that time. The country had just gained its freedom and the Pakistani force was yet to surrender their weapons. “During the tumultuous time of December 16, 1971, we decided to publish a one-page newspaper the following day. The text was written in red ink to signify the bloodshed and lives that the country had lost,” says the editor of The Daily Ajadi, Abdul Malek.

Other popular newspapers during the war were Banglar Bani, a well written newspaper published from Calcutta, Joy Bangla from Naogaon, Joybangla, a mouthpiece of Awami League, published from Mujibnagar, Muktijuddho, a mouthpiece of the Communist Party Bangladesh, Jagroto Bangla, and many others.

Most of these newspapers were printed in cyclostyle, a duplicating process of stencil copying with the help of small-toothed wheels on a special paper, which serves as a printing form. Most of the newspapers and periodicals were two to eight pages, printed in a single colour. The content was mostly sketches of war scenarios in Bangladesh depicting the struggle of people and news of victory of the freedom fighters. The newspapers, periodicals and journals, articles, comments and editorials were a huge source of inspiration for the common people.

Ironically, during the war The Daily Sangram, the lone newspaper known as the mouthpiece of Jamaat-e-Islami, carried enough evidence to expose Jamaat's anti-liberation role. For that reason Sangram has been used as a major source of evidence against the war criminals. During the war, the paper was used as a tool of black propaganda to break the spirit of ordinary people who were supporting the freedom fighters. For instance, an issue of the Sangram published on September 15, 1971 quoted Motiur Rahman Nizami, also the then commander-in-chief of Al Badr, as saying: "Every one of us should assume the role of a soldier of an Islamic country. With assistance of the poor and the oppressed, we must kill those who are engaged in the war against Pakistan and Islam.”

Despite the various attempts at censorship, newspapers continue to thrive. From 1971 till this date, newspapers come under attack for their expression of free speech. Throughout the history of Bangla journalism, journalists have been captured, tortured and murdered for their courageous efforts. However, this has never stopped news from flowing down to the masses.

A newspaper is like a moving image – an image that gives you a picture of the different events, incidents and goings-on of every part of the country in just a single page. While one person living in one end of Bangladesh might never have seen someone from the other end, they feel connected and can relate to each other through newspapers. The nationalist movements of the country grew and spread in a similar manner thanks to the endless efforts of the country's newspapers, be it during the Great India partition, the Language Movement in 1952 or our Liberation War in 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments