Open the Door

The reigning assumption these days about courtesy, civility, and manners is that they are merely frosting on a cake. The clear connection between courtesy and kindness is generally not understood.

All the childhood lessons about saying “please” and “thank you”, not talking only about oneself, not speaking loudly or not asking personal questions are deemed decorative at best and perhaps even unhealthy because they camouflage true feelings. The assumption, one supposes, is that true feelings must be ugly and cruel, and that manners and etiquettes get in the way of their liberating honesty.

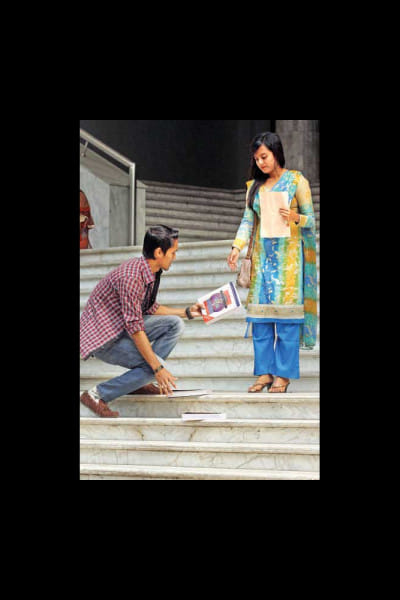

Yet, an older assumption is that manners are indispensable because they elevate our darkest impulses. Courtesy forces people to behave better, kinder than they would.

Respect for ourselves guides our morals; respect for others guides our manners. All the apparently superficial codes of conduct that propel our small, uptight universe of manners and etiquettes are, when one probes to the roots, actually instruments of civility. “Manners are a sensitive awareness of the feelings of others,” Emily Post, famous US etiquette writer observed, “If you have that awareness, you have good manners, no matter what fork you use.”

You are at the bank trying to pay your gas bill. There is a long line of people that has reached the other side of the road. Someone who tries to cut in obviously lacks in manners. But is that all? Is he not being unkind to those who have been standing there for hours?

We live in an era of unsurpassed rudeness—of shouting cell phone users, inconsiderate drivers and shoulder-barging pedestrians—a phenomenon Erving Goffman, the Canadian-born sociologist and writer, considered one of the most influential sociologists of the twentieth century, called "civil inattention".

Gone are the days when travellers would stop by at a random house on the way and call it home for the night. The American South, the bastion of civility and hospitality, where stopping to ask for directions could end in an invitation for supper sees decline in manners.

There is no dress code for anything nowadays because it is thought that formality is undemocratic, an affront to the idea that lets it all hang out. People wore suits and dresses when they travelled. Now, they wear anything or nothing on planes, buses and trains.

The courtesy has been squeezed out of terms of address. E-mails don't use the greeting, “Dear at the beginning of a communication, or sign off with a “Yours sincerely,” or even “Insincerely” at the end. Why say something you don't mean, unless of course you learn to mean it by the very act of saying it.

Some believe over-reliance on technology has created a generation without good manners According to Robin Wells, the founder of Etiquette Manor, Florida, USA, which holds classes on etiquette for adults and children, “teaching manners to children has grown more challenging, and necessary, in part because of technology.”

About three in four people now believe manners have been wrecked by phones, laptops, tablets and social media such as Facebook and Twitter, according to a poll by the modern etiquette guide Debrett's of the UK. A survey among 1,000 people carried out by One Poll, a British marketing research company, found that 77 percent think social skills now are worse than they were 20 years ago, and 72 percent think mobiles have encouraged rudeness.

Others think that journalism is partly to blame. Journalists have been relentlessly eager to go to the bottom of every story by which it really means the bottom. It violates any form of conduct—journalistic or otherwise—when someone asks a man whose whole body has been burnt by a petrol bomb to pose for the camera. This is not to claim that the presumption of an innocent world creates one.

But in the gray area between perfection and sin, where most of us live, a lot can be improved by the sheer display of manners. We just don't want to appear better than we are. We aspire to be better than we are.

The hardest job, however, children face today is learning good manners without seeing much in adults. “Perhaps instead of teaching manners, parents should teach the statistical probability that the person you are speaking to is just as good as you are…”Bertrand Russell observed. “There is nothing like viewing oneself statistically as a means both to good manners and to good morals.”

Ancient poet and philosopher Solomon Ibn Gabriol taught that the test of good manners is to be patient with bad ones. The next time the clerk at the grocery store attends to you while talking on his cell phone, give him the benefit of doubt. And when someone sitting next to you listens to music wearing leaky earphones, don't pick a fight. You will be amazed how effective it can be to tap your fingers amiably to the beat of the leaking music.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments