SAVING THE CINEMATIC PAST

Following a dilapidated corridor, we reach a wooden door, and enter into a dark room. The light flickers for a bit when it is turned on before illuminating the tiny room with its brightness. A huge collection of film cans ranging from the earliest preserved films to the latest day films emerge in front of us.

The archive is a cave of moving images and recorded sounds. On each shelf of the archive, you'll find a film that encapsulates the pop culture of a particular time, thus becoming a principle means of informing and influencing future generations. The Bangladesh Film Archive is a tremendous treasure trove for any film enthusiast of the country. One can find films of Kazi Nazrul Islam, Sergei Eisenstein as well as the legendary films of Zahir Raihan in the collection. The Director General of the Bangladesh Film Archive, Dr Mohammad Jahangir Hossain terms it as preserving history and says, “A film is not just that. It contains the history and culture of a nation, of an era.”

On June 22, 1978, professor Satish Bahadur's concept note on film archiving and the drive of film activists influenced the government to take active steps to preserve the films of a past as well as present and future eras. That very year, the Bangladeshi Film Institute and Archive was established as an office with the then Ministry of Information. Concurrently, the Bangladesh Film Institute and Archive's advisory committee was appointed to work for the future of the archive. From 1984 onwards, it started functioning as the Bangladesh Film Archive.

The beginning was remarkable. AKM Abdur Rauf, founder-curator of the Bangladesh Film Archive sought help from noted freedom fighter and filmmaker, Alamgir Kabir. The duo started a film appreciation programme that helped establish many legendary names of our film industry today, who at that time were mere newcomers.

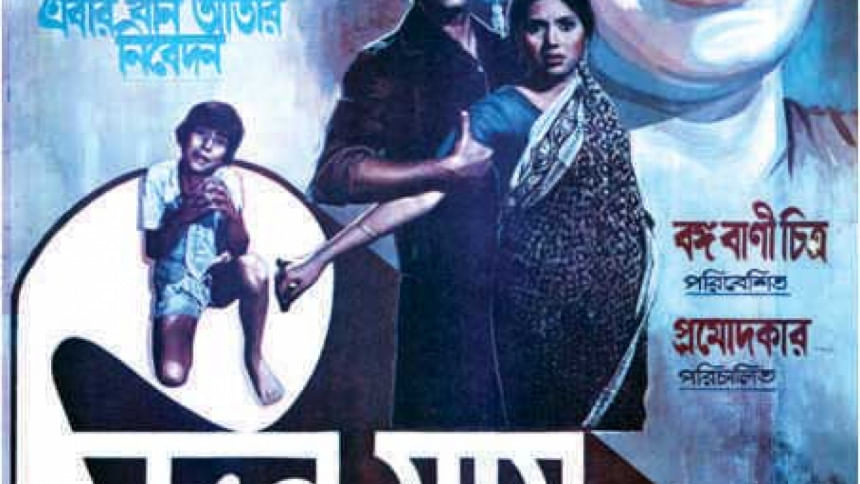

During his tenure as the curator (equal to director general now) of BFA, Rauf visited several film archives across the world and collected priceless documents and prints of films. His collection included a print of Mukh O Mukhosh, photographs of the first silent film made in Dhaka, The Last Kiss, a print of Dhrubo (1934) directed by National Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, Pramathesh Barua's Devdas (1935) and a print of the first silent film made in the sub-continent Dadasaheb Phalke's Raja Harish Chandra (1913).

Amidst financial constraints Abdur Rauf exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. But unfortunately, like many of the endeavours initiated in our country, the archive began to lose its core motives within a couple of decades and became a place to dump old artefacts and objects. The government and authorities concerned have been neglecting the precious collections that narrate the story of our celluloid history. They had even forgotten that an archive is just a container of information; all they needed to do was to appoint a researcher or a film enthusiast to give a sense of form and meaning to the contents preserved in the archive.

It took nearly three decades to revive the archive from its stagnant situation. Fahmidul Haq, Associate Professor of the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, Dhaka University, says, “Dr Jahangir is trying his best to revitalise the archive. We know about the limitations he faced but that has not deterred him. Out of his own interest, he introduced regular seminars, journals and publications and even began research fellowship programmes to raise awareness regarding the archive.” The archive has its own journal, which is the first of its kind published from a film archive in South Asia, along with world class digital post-production and special restoration facilities. Moreover, it has become a platform for film enthusiasts to write, research and watch films on all-year around.

The screenings are held at the archive's newly equipped digital projection theatre every Thursday. The new digital restoration process makes use of chemicals to clean the print. If the print is not too delicate then it is scanned by a digital scanner, which is specifically designed for old prints like Dhrubo or Raja Harish Chandra. The team designated to assess the movies then choose the appropriate restoration method. While some prints are restored in an automated manner, others entail skilled artists to digitally paint in lost information.

The primary constraint in conserving history in sound and film is that much of the prolific output for screen have not been preserved properly. Most of the time, film directors or even collectors of old and rare films are not interested in submitting the films in their possession for archiving. Moreover, the process of preservation depends on institutional arrangements while responsibilities of smooth operations of the archive fall squarely and solely on the shoulders of the person running the department.

Dr Jahangir says, “We are now interacting with independent filmmakers and producers to help people understand the meaning of archiving. It doesn't matter whether the film was a hit or a flop. Within a span of a few decades, a particular scene or shot from any movie might have some cultural significance.”

Different national newspapers have reported that the preservation process of both films and texts related to films are not in good condition due to structural problems. The archive has been operating in different government offices or rented houses since its inception. The new building, specially designed for the archive, is still awaiting its inauguration; it might take another year, if not more, to shift every component of the archive to its new residence. However, by this time, the hot and humid climate of the country and the old structural design of the building might hasten the deterioration of prints, posing a challenge to the state archive's struggle to preserve cinematic history.

The current state of the library is reflective of the years of ignorance and neglect surrounding this organisation. Layers of dust have settled on the shelves; torn magazines and newspapers are strewn around and posters of different films are dumped in some corner or the other. Md Moniruzzaman, Assistant Director of Operations, however believes that the new building designated for the archive can help ease these problems.

Although the present state of the Archive is depressing, it is good to know that we are actually not too far behind when compared to our neighbouring countries. Let's take India for example. The Indian Film Archive came into being in 1964 and launched its digital form as late as 2014. The Bangladesh National Film Archive, meanwhile, has already started working on restoring films digitally.

In the last three decades, the film archive has had its fair share of hits and misses. However, there is still hope for the future. The shift from analogue to digital restoration provides immense promise to save the nation's cinematic heritage. Compared to several other film archives in other countries, the Bangladesh Film Archive has the best of technology and facilities. Now all that is needed is efficient and experienced manpower that can turn the nation's expectations of the archive into reality.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments