Asking the right questions

"Thanks to smartphones and Facebook, 10-year-old children these days know more about relationships and boys than an 18-year-old did 5-6 years ago. Many of the girls here have boyfriends, and they are gossiped about in the community. If she elopes her fate is sealed— no good proposals will ever come her way. Parents who want to avoid such consequences are compelled to think about their daughter's marriage as soon as she is an adolescent."

– A community school teacher in an urban slum neighbourhood of Dhaka.

In the face of scathing criticism from local and international activists and human rights groups about what qualifies as a "special case", here I am pondering if we truly understand the challenge at hand. Is it only about the age? Is marriage even a choice for the 19 million adolescent girls in Bangladesh?

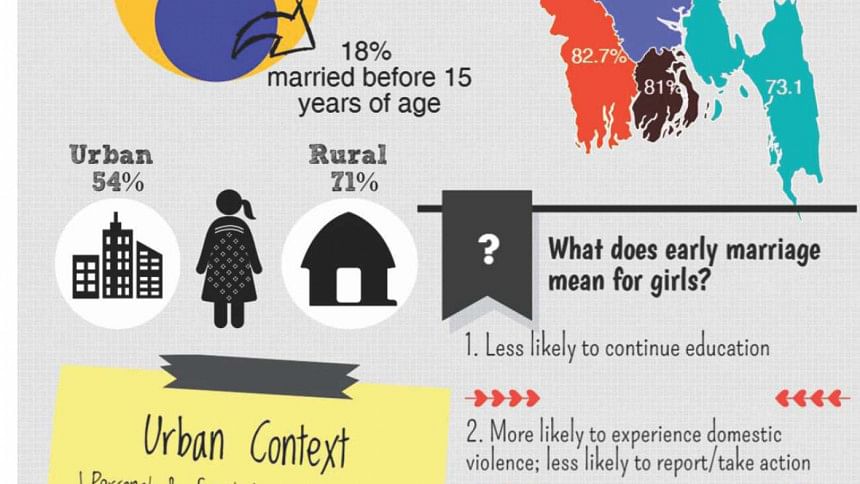

While there have been numerous efforts to address child marriage in many parts of the world, dating as early as the 1920s, the issue remains widespread and doggedly constant. Consider the following stark numbers. One third of girls in the developing world are married before the age of 18 and 1 in 9 are married before the age of 15 (ICRW, 2016). According to recent BDHS data, 6 out of 10 girls in Bangladesh are married before the age of 18. And of those, around one-third of adolescent girls aged 15-19 are already mothers or pregnant.

Some are forced into marriage at a very early age. Others are merely too young to make an informed decision about their partner or about the implications of marriage itself. They may have given what passes for 'consent' in the eyes of custom or the law, but in reality, consent to their binding marital contract has been made by others on their behalf. Without getting into the debate over exceptions and "special cases" of marriage-age laws, this article is to remind ourselves the socio-cultural challenges that remain deeply rooted: rights and control of girls' bodies, aspirations and choice.

In the last 10 years, Bangladesh has moved up the ranks from having the third highest rate of child marriage in the world to the eighth highest as of 2016. But whether the upward trend will continue is difficult to predict given the shifting legal landscape.

For both girls and boys, early marriage leads to profound physical, intellectual, psychological and emotional impacts, often interrupting education and hindering personal growth. For girls, in addition, it will almost certainly mean premature pregnancy and childbearing, and is likely to lead to a lifetime of domestic and sexual subservience over which they have little or no control.

Despite these well-known disturbing consequences of child marriage as well as the efforts around the world to end it, its persistence leads one to ask, what are the complexities that perpetuate the situation?

While there's several research and programmatic work around early/child marriage in rural areas, few studies have attempted to explore the causes and consequences of child marriage in the context of growing urbanisation. There are significant gaps in literature about how the unique economic and social realities of urban slums, including the constant risk of eviction, congested living conditions, threats of sexual violence, erratic employment opportunities, etc., affect early marriage. With the onset of tremendous urban growth and the opportunity to understand the issues and feed into programmes in Bangladesh, the need for this exploration is ever-so-critical.

According to population scientists, Dhaka is on its way to becoming the sixth largest mega-city in the world by 2030. About 9 percent of the Bangladesh population lives in the Dhaka metropolitan area, which contributes to 36 percent of the country's GDP. Every day, 1,000 migrants enter Dhaka in search of economic opportunities. The heavy influx of migrants accounts for an increasing percentage of urbanites living in slums and squatter settlements. As a result, about 15 percent of the overall urban population of the country resides in urban slums. And here's the challenge: despite having the highest level of NGO interventions focused on adolescents, Dhaka still has a higher prevalence of early marriage (77.6 percent) than other divisions like Sylhet (62.5 percent) and Chittagong (73.1 percent).

Urbanisation has brought in a number of idiosyncrasies, challenges, opportunities and dilemmas that we, as researchers, are struggling to make sense of. Many would argue that urbanisation in the form of garment factories has allowed economic empowerment for young girls (4 million RMG workers of which 80 percent are young women) and delayed marriage for a lot of them. This has also afforded mobility for young girls and ease of access to mobile phones which perpetuate incidences of love relations leading to early marriage and elopement (reported by many community members). And although young adolescents seem to enjoy this freedom, many of the same girls who experience divorce and abandonment from spouses are subject to social stigma. On the other hand, delaying marriage is associated with higher dowry costs. In fact, dowry costs tend to go up with age, education and the nature of employment. To connect the dots, has the factory job, that imposes a higher dowry, truly empowered the young woman? If the opportunity to work has delayed marriage for young girls, has it also translated to a better marital life afterwards? Or has the delay tainted eligibility for marriage?

There are more of these paradoxes. Consider the effects of modernisation and creeping conservatism. Young boys in urban slums are often seen sporting buzz haircuts, wearing the latest trends of tees with pop-culture references and dancing to Hindi soundtracks. Girls in urban slums are seen wearing leggings, make-up and false eye-lashes. The influence of media is evident in their aspirations. And yet girls are victimised and shamed when spotted talking to a boy who is not family. The slum is a place where existing gender norms are re-inscribed and upended. Peppered through the social and class-based system, notions of masculinity and femininity exist and collide with each other. During research, we've met bold, outspoken females who shoulder the entire family's responsibilities (paying bills, tuition, loans, and entrepreneurial pursuits) and dominate decision-making, and we've also encountered socially secluded passive married adolescent girls who are afraid to talk to us in front of their husbands.

It's heartening to see that the trend of early marriage has certainly improved over the years, albeit the rate of change has been sluggish. Median age at first marriage for women aged 20-49 years has increased from 14.4 years in 1993-94 to 16.1 years in 2014 (NIPORT et. al, 2016). In the last 10 years, Bangladesh has moved up the ranks from having the third highest rate of child marriage in the world to the eighth highest as of 2016. But whether the upward trend will continue is difficult to predict given the shifting legal landscape. What we do know for certain is that there is no silver bullet to solve this issue, and there is an inherent need for qualitative research and substantial long-term interventions to capture and address the process of change. The veil of silence is slowly lifting, and the government has put the problem on the global agenda, pledging commitment to end child marriage by 2041.

The James P. Grant school of Public health through its Centre for Gender and SRHR has been instrumental in supporting the national goal of ending child marriage through multiple research projects focusing on adolescents and their sexual and reproductive health rights. The school leverages on strategic partnerships and alliances to explore the issue of child/early marriage from social, health and legal perspectives. One of its current projects is investigating the underlying issues that influence early marriage in urban slums and exploring factors that lead to delaying marriage until 18 years of age. This study will also look at two key existing interventions in Dhaka city and identify successes, challenges and lessons learned. The results of this study are expected to generate evidence-based communication messages and invoke thoughtful dialogues among government, programme implementers and donors and other stakeholders and promote more effective interventions. We hope to address some of the unmet and latent needs of adolescents living in urban slums through this research.

The writer is a project manager at the Centre for Gender and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights, James P. Grant School of Public Health. She is currently working on a research project focused on early/child marriage in poor urban settlements of Bangladesh, led by Professor Dean Sabina F. Rashid and funded by IDRC, Canada.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments