Administrative Civil Service in Bangladesh: Its legacy and role

In his seminal publication -- The Men who ruled India (1985) -- Philip Mason, in the last paragraph of the epilogue wrote: "When all has been said, one simple point remains. It was put clearly by Lord Wavell (Governor General and Viceroy of India before Lord Mountbatten) in an informal speech made after he left India. The English would be remembered, he believed, not by this institution or that, but by the ideal they left behind of what a district officer should be. At the other end of the long link Warren Hastings (the first Governor General of British India) had expressed a similar thought. It is on the virtue; he had said, 'not the ability of their servants that the Company must rely.' And if today, the Indian peasant looks to the new district officer of his own race with the expectation of receiving justice and sympathy that is the memorial to the English. Here the District officer -- DC -- represents administration in general."

Mason wrote this in 1985, about four decades after India's experience as a working liberal democracy: For our understanding, the word 'Indian' in the paragraph may be replaced by 'Bangladeshi'.

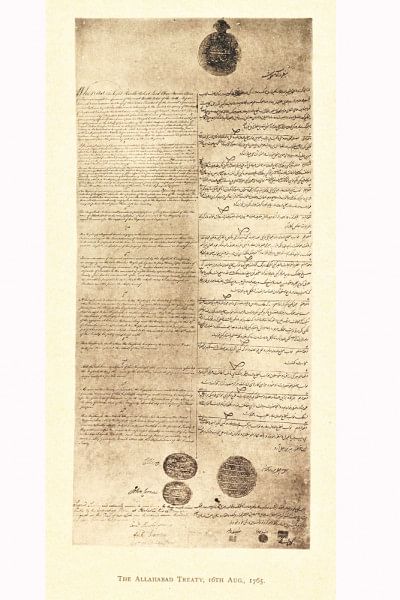

The British inherited the Dewani and Fauzdari system of administration of the Mughals, and over the years, kept on modifying and adjusting the same to respond to their needs. We may recall that in 1765, the weakened Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II issued a farman that replaced the Mughal Revenue officials in the province of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa with the East India Company's. However, the British (East India company) found that the Mughal system worked very well. In 1700, as Shashi Tharoor (eminent Indian politician and author) in his book (2016) 'Inglorious Empire' pointed out, India, under Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, accounted for 27% of the World economy. In the initial period, the modified versions of the posts of Nizam, Kotwal. Munsiff, Sadar Amin, Quazi, Hakim and expressions like (most of which still persist) Zilla, Vakil, Quanoon, Mukhtar, Sherestadar, Kist, Nazarath, Peshkar, Nazim, Nayeb, Tehsil, Khajanchi, Mohafezkhana, Hefazat, Jameen, Shumari etc. continued to remain. The Mughals emphasized on the secular nature of bureaucracy. Revenue collection agents called Chowdhury (they were land owners, but authorized to retain 'chauth' 1/4th of the collection), Majumder, Kanungo, Tarafdar, Mirashdar etc. could belong to any community. But the British did otherwise. The Hindu entrants to governmental jobs had the Prefix Babu, and Musalman had 'Maulavi'. However, ICS and listed post holders of PCS were excluded from this divisive practice as they were expected to be anglicized. Even in cases of honour-awards, Muslim recipients were called Khan Bahadur, Khan Saheb, and the Hindus were called Roy Bahadur, Roy Saheb. As Shashi Tharoor wrote : 'The sight of Hindu and Muslim soldiers rebelling together in 1857 and fighting side by side ... willing to pledge joint allegiance to the enfeebled Mughal Monarch (Bahadur Shah Zafor) had alarmed the British, who did not take long to conclude that dividing the two groups and putting them against one another was the most effective way to ensure the unchallenged continuance of the Empire and hence this 'divide et impera'.

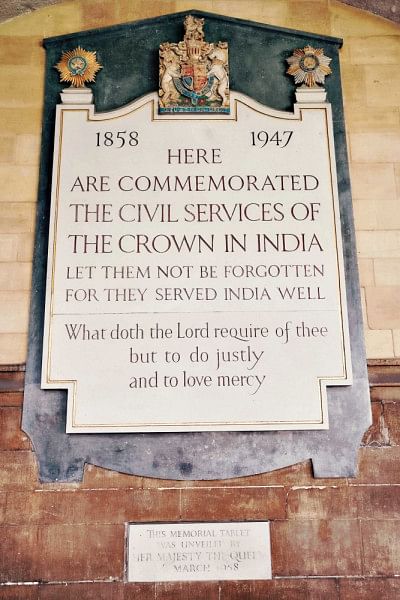

It was only in 1835 that English was made the official and court language of India replacing Persian. The British Civil and Military officials were however taught Urdu/Hindustani as an unofficial lingua-franca, but in Roman script. In 1858, Queen Victoria, by a proclamation took over, in the name of the Crown, the governance of India from the East India Company and the Civil Service Jobs were made open to the Indians.

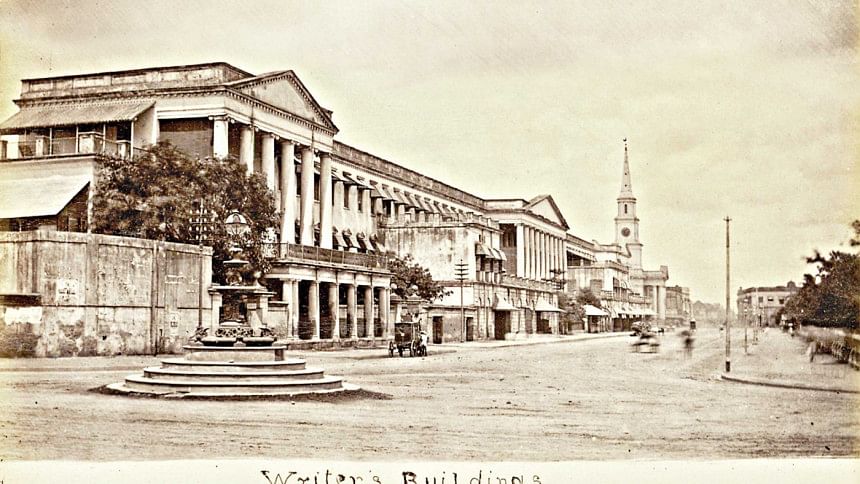

Apparently, the British took rather a long time in effecting significant reforms as they realized that the Mughal System of conducting administrative affairs through a Corps of trained officials in revenue and judicial matters working under an appointed Subedar (Governor) worked very well in the sub-continent. The British had earlier in 1767 established their capital in Calcutta. They organized the central administration in Writers' Building, which was actually the Secretariat.

The chief district officer was designated as District Magistrate, Collector, or Deputy Commissionar, a designation that varies from province to province. Since revenue collection was their primary responsibility in the early days, their office was generally known as collectorate. Subsequently all governmental activities in the district came under his direct or indirect supervision or monitoring including, of course, magistracy and maintenance of law and order, development programmes, relief and land management, coordination and information dissemination. In lesser degree, the same sort of activities were conducted by the Sub Divisional officers (SDO). The secretariat at the policy-making level was manned by a structured hierarchy with positions like Secretary, assisted by Additional, Joint, Deputy, Assistant and so forth. The system continued, even after India and Pakistan (including East Pakistan which emerged as independent Bangladesh) became Republics with some modifications and adjustments. In Bangladesh, DC is called Zilla Proshashok, in Pakistan, sometimes DC or Nazim and in India, called Zilla Shashok or Upayukta (coordinator) in some states, Zila Dandadhikari.

In Bangladesh, all the subdivisions have become districts and almost all the thanas were made Upazilas / Subdistricts with the chief administrative officer designated as Upazila Nirbahi Officer (UNO) or Sub-district Executive officer. In all fairness, the post should be, I feel re-designated as SDO or sub-district officer correctly reflecting the type of duties the incumbent has to perform.

Though Bangladesh was the product of a popular revolution, immediately after the proclamation of independent government on 10th April 1971, Laws Continuance Enforcement Order 1971 was promulgated which laid down that "all government officials, civil, military, judicial and diplomatic, who take oath of allegiance to Bangladesh shall continue in their offices on terms and conditions of service so long enjoyed by them…"

I have had the privilege of being DC of Jashore, the first settled district in British India, where my father, Ghyasuddin Ahmed Chaudhury, a civil servant, also served as DC. I looked through old papers and correspondence, copies of which were retained in the confidential office and record room. It was interesting to note that the District officers, through their fortnightly confidential reports, which were frank, analytical and forthright, occasionally containing bold and innovating suggestions, kept the authorities informed. The officers were encouraged to act without fear or favour, and they received protection in cases of genuine difficulty or when under pressure. An espirit de corps prevailed. Unfortunately, this seems to be missing now.

When the British left India, the number of Bengalee Muslim officials in administration or elsewhere was negligible. There was only one serving ICS officer and a few senior officers in the 'listed post'. The situation was tackled with great dexterity. Professor Khalid Bin Sayeed in his book -- 'Pakistan, the formative phase'-- gave a list of Muslims in the Civil and Military Service in the Government of India, 1946-47.

Dr. Akbar Ali Khan in his 'Gresham's Law Syndrome and beyond' states that from 1949 to 1970, 458 appointments were made to the CSP out of which 185, some say a little more, were Bangalees.

The Quota system helped a great deal. All (about) 600 appointees to the PCS in this period were Bengalees. Kabedul Islam in his book in Bengali 'Role of CSP-CPCS officers in the Liberation war' and Dr Akbar Ali Khan, in his book, inter alia describe how the Bengalee Civil servants in Administration (also in other branches) took momentous decisions at the most critical phase of our nation, and almost as a duty, identified themselves with freedom fighters.

I recall that in the second week of March 1971, The CSP Association (East Pakistan) under the chairmanship of SM Hasan, (ICS-CSP from Punjab) unanimously decided that in this critical juncture of the country's history, the member of the Association should express their due support and their willingness to extend assistance, from their respective positions to the constitutional process of formation of governmental authority by the leader of the political party having the support of the majority in the elected Parliament… Bangabandhu greatly appreciated this gesture, and held this in fond remembrance.

In independent Bangladesh, a unified Civil Service System was introduced where all cadre services, were theoretically equal. Existing cadres were merged and abolished and new cadres created in the process. Under the Bangladesh Civil Service Order 1980, and subsequent modifications, the BCS (Adm) Cadre comprises former CSP, EPCS, BCS (Sectt) and IMS.

In the proper functioning of a Parliamentary democracy, the efficiency and effectiveness of officers of this cadre is of utmost significance. Since public dealings are involved, they will be expected to have the capacity of attaining people's confidence. They are servants of the Republic, and should have public service topmost in their consideration, They are supposed to play a supportive role for the elected people's representatives and political leaders in the government in due discharge of their constitutional obligations and responsibilities. And yet, the Cadre-members will be expected to maintain their image of objectivity, neutrality and incorruptibility. As Dr. Akbar Ali Khan observes: 'a generalist administrator is a specialist in administration, and is not an amateur."

The art of administration is indeed complex and requires expertise of its own. Its horizon would be ever-expanding, but the secretaries and the field administrators like Commissioner, DCs and their associates will continue to remain kingpins in the governmental machinery, particularly in a parliamentary democracy, as practiced in our country. For the sake of good governance, it is essential to ensure that these officers are adequately trained, equipped and enabled, are free of corruption, and remain responsible to the constitutional authority.

The challenge is enormous.

Enam Ahmed Chaudhury is a former Chairman of the Privatisation Commission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments