Bangladesh liberation war memories: An Untold Story

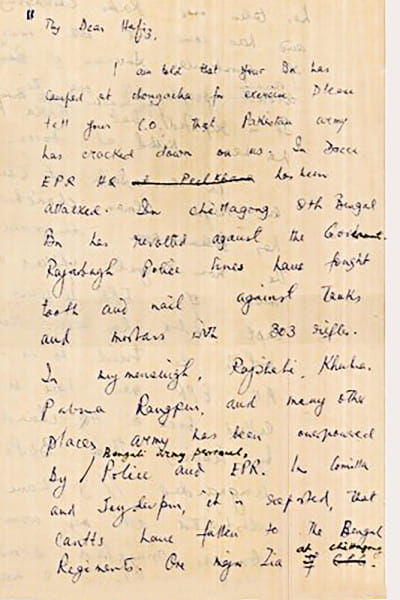

I had written this letter to my friend Hafiz who was then a Lieutenant of the 1st Bengal regiment and was in winter exercise in Chowgacha Police Station of the then Jashore district adjacent to subdivision Jhenaidah where I was posted.

The letter is reproduced below:

"My Dear Hafiz,

I am told that your Bn [Battalion] has camped at Chowgacha for exercise. Please tell your CO [Commanding Officer] that the Pakistan army has cracked down on us. In Dacca, EPR [East Pakistan Rifles] HQ has been attacked. In Chittagong, 8th Bengal Bn has revolted against the Government. Rajarbagh Police Lines have fought tooth and nail against tanks and mortars with 303 rifles. In Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Kustia, Pabna, Rangpur and many other places, the army has been overpowered by Bengali army personnel, Police and EPR. In Comilla and Joydevpur, it is reported that cantonments have fallen to the Bengal Regiments. One Major Zia at Chittagong has taken over Radio Chittagong and has come out with news of spectacular successes of Muktibahini all over the country. It is reported by Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendro that Tikka Khan has been killed at Dacca.

In our sector at Chuadanga, one Major Osman Chowdhury has disarmed all the non-Bengal officers and men of EPR 4-Wing. One Capt. Sadek has been killed while he tried to be funny. All EPR men have been called back to HQ Chuadanga by leaving the BOPs [Border Outposts] unguarded.

I have distributed all my arms to Ansars, mujahids, students and volunteers. I have nearly two hundred police men armed with 303 rifles and twenty rounds of ammunition per rifle. Another 800 ansars with an equal number of rifles have volunteered to fight the Pakistani hordes. I feel, you, along with your Bn, arms, and equipment, should join me. This is the most crucial hour of the nation. Please tell your CO that East Pakistan is dead, and we are at war. We need you."

The letter was written on March 27, 1971. I sent the letter through my special messenger, Danesh. He returned the next morning and said, "Sir, I reached the Camp with many difficulties. But the sentries wouldn't let me in. I requested them to hand the letter over to one of their Bengali officers. They wouldn't accept."

I was upset, but nothing could be done. I sent another letter addressed to Colonel Jalil through the same messenger. This time the letter was passed on, but no reply came.

On March 29, to my utter dismay, I was told that Lt. Colonel Jalil and his Battalion were going back to Jashore Cantonment as ordered by Brig. Durrani. I felt like a paralysed person. Is the CO off his head? Does he not know anything? Has he lost all communication with the world? Has my cry fallen on deaf ears? Have my letters reached them? These questions and hundreds of others flickered through my mind.

On March 30, at about mid-day, I received the first news of the massacre on the 1st Bengal Regiment at Jashore Cantonment. People from Jashore telephoned to inform me that a serious fight was happening inside the cantonment. 1st Bengal finally revolted, but nobody could tell who was winning. For five hours, we at Jhenaidah counted moments in great anxiety. From time to time, telephone exchange at Kaliganj gave me first-hand reports of the exchange of fires and bombing. I was terrified. How could the lone Bengal Bn fight against 55 FD Regiment, nine Punjab and 11 Baluch?

My apprehension proved correct when the runaway Bengali soldiers started pouring into my HQ at Jhenaidah with horrifying tales of the massacre the following day.

During these critical days, what moved me most was the spontaneous upsurge of people. It is impossible to describe how the entire rural populace transformed itself into one whole force throbbing with life and willing to bathe in a flood of blood to emancipate itself from a barbarous tyrant. To an impartial observer, this was the will of a nation to establish truth and justice by overpowering brute force. It was a historic moment for the world.

Why am I writing this untold story now?

I always felt that if 1st Bengal had joined us with its arsenal of weapons, 27 Baluch, the most powerful motorised column of the enemy, would have been mauled and destroyed, and their entire arsenal and vehicles would have been in our possession. With most of the Muktibahini contingents having set up around Jashore cantonment, it would have been a matter of time and planning to run over the cantonment and capture it. As a result, our movement to the Indian territory would have been delayed or not required at all. The story of the gallantry of the people of Bangladesh would have been written differently.

One blunder of a commander was so costly in the annals of our liberation war. I am sure the historians would also look at it from this angle. In this context, it is relevant to state here that before launching their most serious three-pronged thrust on us from Jashore cantonment, with Dhaka-Goalundo axis and aerial staffing and bombardment centring Kushtia and Hardinge bridge, the Pakistani troops in Jashore had raised the white flag in a deceitful gesture to escape the anticipated wrath of being run over by the Muktibahini. By then, most of the supply sources of ordinary ration and other items of survival for the troops in the Jashore cantonment had been shut down by the Bengali vendors, and the ordinary troops were trying to leave the cantonment.

We can recall that this heavy-handed action on our stronghold at Paksey around Hardinge Bridge had been achieved by Pakistan after suffering a severe loss and debacle at Goalundo. It was undertaken only after the heavy reinforcement brought from Pakistan.

A TRIBUTE TO DANESH

He was a motor mechanic. He used to run his auto shop in Jhenaidah town with his brothers, Yunus, the eldest, Anis, Sanis, and cousin Malek. Originally they hailed from Sreenagar of Munshiganj subdivision. In the wee hours of the liberation war, and the very initial phase of resistance on March 25, 1971, midnight, he started helping the war efforts in his humble way. He had a motorcycle, which was immensely useful to make quick movements to exchange intelligence. It was vastly helpful because when the roads were blockaded by felling trees, cutting trenches, and leaving obstructive objects, his motorcycle would navigate through cultivable lands under his very expert and adept hands. On my very first move to Chuadanga from Jhenaidah (March 27, 1971) on a mission to meet Major Abu Osman Chaudhry in his hurriedly assembled headquarter at Chuadanga Dak Bungalow, I was driven by Danesh on his motorbike because my jeep would take hours to navigate through cultivated and swampy land. This was the beginning of Muktijoddha Danesh Sarder, my motor mechanic, an expert driver for any vehicle, light or heavy, and my lifelong friend.

This was the Danesh Sarder I sent to Lt. Col. Jalil, CO of 1st Bengal Regiment. He was a heavy-set young man with thickset straight black hair falling to his neck, dark for any Bengali youth, muscular, of medium height around 5'10", full of life, fun-loving, carefree, and mostly dressed in white slacks and a shirt.

In the Theatre road where the Mujibnagar government had its office, his large Cadillac-like long-body vehicle was ready to carry anyone among the big shots who would need him as a chauffeur on instant notice. Such was his candour and readiness throughout the nine months wherever we went, in his transport. It was a car of Joy Bangla in Kolkata and would be looked at, even by Kolkata police, with some degree of awe and respect.

Danesh and his brothers had moved like our shadow ever since the liberation war started. When we withdrew to a safer position at Meherpur along with our troops and soldiers, they continued with us. They were witnesses to the oath-taking ceremony of the first independent Government of Bangladesh at Mujibnagar.

My last important war zone destination was Satkhira with Itinda at the backyard near the Indian border, 24 Parganas adjacent to the Sundarbans North-West corner. As a matter of routine, a few squad strength contingents would go out on guerrilla missions every night there, and Danesh and brothers would always be in those expeditions. In one such expedition, in a fight with Rajakars, his eldest brother Yunus was wounded with a javelin thrown on his companions by the Rajakar band. He was hit at the right side of his chest and given first aid. Later on, he was given treatment by a local doctor. Luckily, it was not so dangerous a wound.

On April 24, when our troops were stationed in Benapole, and we were under the bombardment of the Pakistan Artillery, Danesh drove my companions and me in my jeep through the bombings to a safe zone from Benapole on Benapole Petrapole road. This was a life-threatening drive through fire and peril and needed a daredevil to speed through falling artillery shells. He held onto the wheel of our jeep without a hint of fear in his bones. Such was his courage in the face of danger on the battlefield.

To cut a long story short, he returned to Dhaka with me victorious, started his search for a better life, took to some form of leadership in the transport labour sector, especially the baby taxi drivers and workers, was generally managing so as long as Bangabandhu was alive. I held a powerful position in the government hierarchy. With the sudden death of Bangabandhu when I was imprisoned for being a threat to the then military government, his fortune declined.

Danesh left us all on an eternal journey on Monday, December 20, 2021, virtually unattended in an ICU unit of Dhaka Medical College Hospital. A tragic end of a courageous freedom fighter.

Mahbub Uddin Ahmed Bir Bikram was the sub-divisional police officer of Jhenaidah during the Liberation War. He was in charge of presenting the guard of honour to the Acting President of Bangladesh Government-in-exile, Syed Nazrul Islam, at the oath-taking ceremony on April 17, 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments