Bishop Heber in Dhaka,1824

Bishop Reginald Heber (1783-1826) was an Oxford educated Anglican clergyman from England, a man of letters and a notable hymn-writer. As an intrepid traveler and a curious observer, he has left behind an interesting travelogue entitled: 'NARRATIVE of A JOURNEY through the UPPER PROVINCES OF INDIA, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825.' His multi-faceted qualities, expertise in Christian theology and amiable disposition empowered him to ascend the rungs of the ecclesiastical order with ease. He was ordained as the metropolitan Bishop of Calcutta in 1823. In this essay, I have highlighted some choicest excerpts from the main episodes of Bishop Heber's interesting 18-day stopover in Dhaka from 4th July - 22nd July, 1824, on his way to upper India. His journal incorporates an important historical chronicle on Dhaka and its environs during the nominal rule of the titular Nayeb-e-Nazim, Nawab Shams-ud-Daulah. His vivid description remains a noteworthy account by a distinguished foreigner of early 19th century Dhaka, by then a city very much in decline. The itinerary plan of Heber's grand tour of north India, was to sail northward up the river Hooghly into the Ganges and, then strike off eastward to Dhaka which was to be his first place of importance to be visited along the way. From Dhaka he decided to sail west up the Ganges as far as possible and eventually make it to the south to reach Mughal Delhi and, finally go down to Bombay from there. As a general guide he consulted the famous map of James Rennell, the first surveyor-general of Bengal in the latter part of 18th century. However, by Heber's time the major river systems and its numerous tributaries had considerably altered its character since the days of Rennell, therefore, the map was often misleading.

Having reached the outskirts of Dhaka, Heber wrote, "I preached to a small congregation, in a very small but pretty Gothic Church". However, he does not identify the church. I am convinced that he surely meant the Church of St. Nicholas Tolentino at Nagori, which can be reached from the Tongi-Kaliganj highway towards the south in the village of Nagori. It is the earliest surviving church in Bangladesh, which was built in 1663, and displays distinctive Gothic features. Heber further observed that, "The river on which Dacca stands (read the Buriganga), has greatly altered its character since Rennell drew his map in 1776. It was then narrow, but is now, even during the dry season, not much less than the Hooghly at Calcutta. At present it is somewhat wider". According to Heber, the first buildings he sighted in Dhaka were the ruined towers of old Dhaka, presumably those of the Lalbagh fort. While approaching the shore a peculiar noise drew his immediate attention which seemed to come from the waters of the Buriganga river. The sound was long, loud, deep and tremulous, something between the bellowing of a bull and the blowing of a whale. Soon he became aware that the noise emanated from about twenty bathing elephants, with their heads and trunks just appearing above the water. Heber thus wrote, "Dacca is much place for elephants. The Company have a stud of from 2 to 300, numbers being caught annually in the neighbouring woods of Tipperah and Cachar, which are broken in for service here, as well as gradually inured to the habits which they must acquire in a state of captivity." While on the subject of elephants, the noteworthy antiquarian of Dhaka S. M. Taifoor in his book, 'Glimpses of Old Dhaka', 1956, wrote," Towards the west of the city there is a big stretch of field called Pilkhana which is now the headquarters of the East Pakistan Rifles. This was the government field of the East India Company for breaking in elephants. In Moghal times there had been another bigger field to the north of the city."

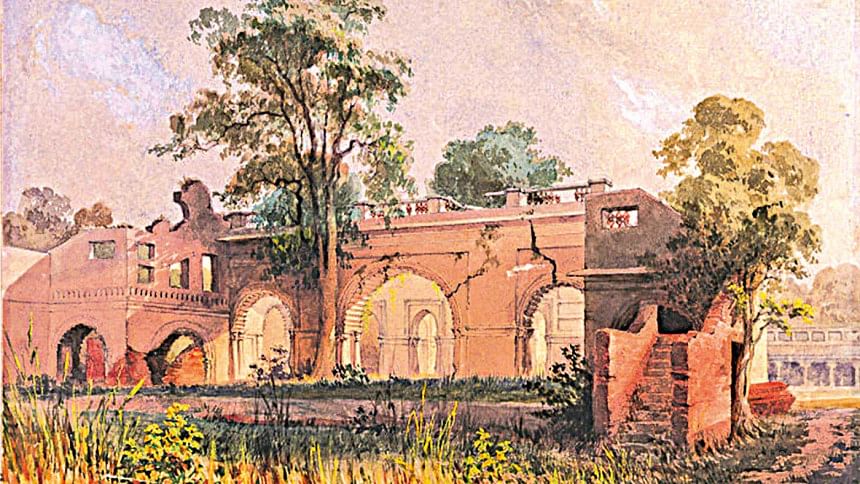

This paragraph contains an interesting impression of Dhaka by Bishop Heber whose host and guide Judge Masters, gave him a short brief on the current status of the city which he diligently entered in his dairy, for he wrote, "Dacca, Mr. Masters says, is, as I supposed, merely the wreck of its ancient grandeur. Its trade is reduced to the sixtieth part of what it was, and all its splendid buildings, the castle of its founder Shah Jehanguire, the noble mosque he built, the palaces of the ancient Nawabs, the factories and Churches of the Dutch, French, and Portuguese nations, are all sunk into ruin, and overgrown with jungle. As for the English there are none, except a few indigo planters in the neighbourhood, and those in the civil or military service. But the Hindoo and Mohammedan population, Mr. Masters still rates at 300,000. I drove in the evening, with Mr. Masters, through the city and part of the neighbourhood. The former is very like the worst part of Calcutta near Chitpoor, but has some really fine ruins intermingled with the mean huts which cover three-fourths of its space. The castle which I noticed, and which used to be the palace, is of brick, yet showing some traces of the plaster which has covered it. The architecture is precisely that of the Kremlin of Moscow, of which city indeed, I was repeatedly reminded in my progress through the town. The Grecian houses, whose dilapidated condition I have noticed, were the more modern and favorite residence of the late Nawab, and were ruined a few years since by the encroachments of the river. The Pagodas of Dacca, are few and small, three-fourths of the population being Mussulmans, and almost every brick building in the place having its Persian or Arabic inscription. Most of these look very old, but none are of great antiquity. Even the old palace was built only about 200 years ago, and consequently, is scarcely older than the banqueting-house at Whitehall. The European houses are mostly small and poor, compared with those of Calcutta; and such as are out of the town, are so surrounded with jungle and ruins, as to give the idea of desolation and unhealthiness. No cultivation was visible so far as we went, nor any space cleared except an area of about twenty acres for the new military lines (read Purana Paltan).The drive was picturesque, however, in no common degree; several of the ruins were fine, and there are some noble peepul-trees."

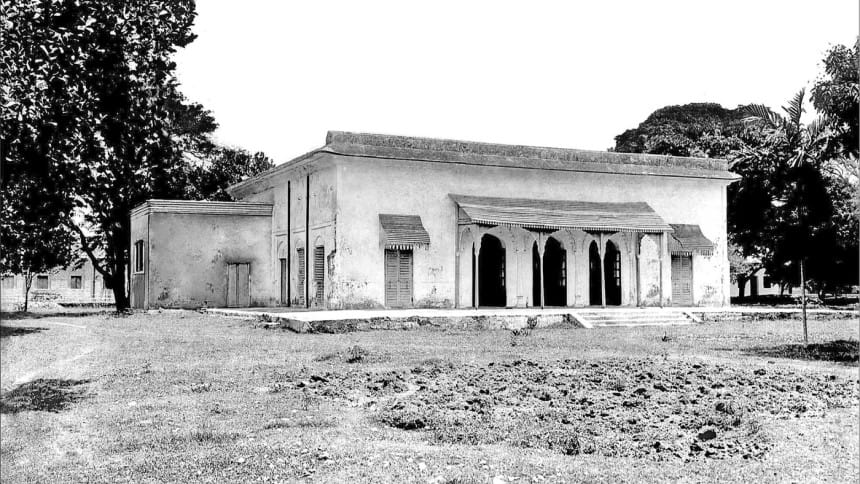

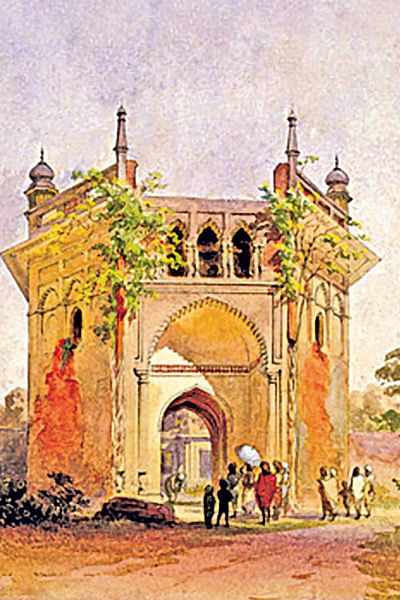

On July 6, Heber noted: "The Nawab called this morning according to his promise, accompanied by his eldest son. He is a good looking elderly man, of so fair a complexion as to prove the care with which the descendants of the Mussulman conquerors have kept up their northern blood. His hands, more particularly, are nearly as white as those of a European. He sat for a good while smoking his hookah, and conversing fluently enough in English, quoting some English books of history, and showing himself very tolerably acquainted with the events of the Spanish war of succession. His son is a man of about thirty, of a darker complexion, and education more neglected, being unable to converse in English". On July 8, Heber further entered in his diary, "In the afternoon I accompanied Mr. Masters to pay a visit to the Nawab, according to appointment. We drove a considerable way through the city, then along a shabby avenue of trees intermingled with huts, then through an old brick gateway into a sort of wild-looking close, with a large and some bushes in the centre, and ruinous buildings all around. Here was a company of Sepoys, drawn up to receive us, very neatly dressed and drilled, being in fact a detachment of the Company's local Regiment, and assigned to the Nawab as a guard of honour. In front was another and really handsome gateway (see Figs: 01 & 03), with an open gallery, where the "Nobut," or evening martial music, is performed, a mark of sovereign dignity, to which the Nawab never had a just claim, but in which Government continue to indulge him. Here were the Nawab's own guard, in their absurd coats and caps, and a crowd of folk with silver sticks, as well as two tonjons and parasols, to convey us across the inner court. This was a little larger than the small quadrangle at All Souls, surrounded with low and irregular, but not inelegant buildings, kept neatly, and all white-washed. On the right-hand was a flight of step leading to a very handsome hall, an octagon, supported by gothic arches, with a verandah round it, and with high gothic windows well venetianed. The octagon was fitted up with a large round table covered with red cloth, mahogany drawing-room chairs, two large and handsome convex mirrors, which showed the room and furniture to considerable advantage, two common pier-glasses, some prints of the king, the emperor Alexander, lords Wellesley and Hastings, and the duke of Wellington, and two very good portraits, by Chinnery, of the Nawab himself, and the late Nawab his brother. Nothing was gaudy, but all extremely respectable and noblemanly. The Nawab, his son, his English secretary, and the Greek priest whom he had mentioned to me, received us at the door, and he led me by the hand to the upper end of the table. We sat for some time, during which the conversation was kept up better than I expected; and I left the palace a good deal impressed with the good sense, information, and pleasing manners of our host, whose residence considerably surpassed my expectations, and whose court had nothing paltry, except his horse-guards and carriage."

After bidding farewell to the Nawab, Heber went to visit the house of a premier nobleman of Dhaka, Mir Ashraf Ali Khan, whose estate was almost adjacent to the Nayeb-e-Nazim's palace. He wrote, "I went from the palace to the house of Meer Israf Ali, the chief Mussalman gentleman in this district. He is said by Mr. Masters to have been both extravagant and unfortunate, and therefore to be now a good deal encumbered. But his landed property still amounts to above 300,000 begahs, and his family is one of the best (as a private family) in India. He was himself absent at one of his other houses. But his two eldest sons had been very civil, and had expressed that I would return their visit. Besides which, I was not sorry to see the inside of this sort of building. Meer Israf Ali's house is built round a courtyard, and looks very much like a dismantled convent, occupied by a corps of Uhlans. There are abundance of fine horses, crowds of shabby looking servants in showy but neglected liveries, and on the whole a singular mixture of finery and carelessness."

During his Dhaka visit, Bishop Heber, consecrated and held a sermon at the St.Thomas Anglican Church built in 1821 and, also visited the old Anglican Christian cemetery at Narinda, for he wrote, "I consecrated the burial-ground; a wild and dismal place, surrounded by a high wall, with an old Moorish gateway, at the distance of about a mile front the now inhabited part of the city, but surrounded with a wilderness of ruins and jungle. Some of the tombs are very handsome; one more particularly, resembling the buildings raised over the graves of Mussulman saints, has a high octagon Gothic tower, with a cupola in the same style, and eight windows with elaborate tracery. Within are three slabs over as many bodies, and the old Durwan of the burial-ground said, it was the tomb of a certain " Columbo Sahib, Company ka nuokur," Columbo, servant to the Company; who he may have been I know not ; his name does not sound like an Englishman's, nor is there any inscription. Another evening I went in a beautiful boat of Mr. Milford's to the 'Pagla Pwll,' or mad bridge, a ruin four miles below Dacca. It is a very beautiful specimen of the richest Tudor Gothic, but I know not whether it is strictly to be called an Asiatic building, for the boatmen said the tradition is, that it was built by a Frenchman. There is a very fine and accurate engraving of it in Sir Charles D'Oyly's 'Ruins of Dacca'."

Epilogue: Bishop Reginald Heber left Dhaka with fond memories on 22 July, 1824, retracing his route to the junction of the Ganges and Hoogly rivers for upper India (Mughal Delhi). Sadly, after a short eventful life he suddenly died of 'seizure' contracted from a fatal chill after a cold bath in the hot weather of Trichnapalli, South India, at the age of forty-two in 1846. His arduous pastoral tours to far flung areas on evangelical missions and exposure to inclement weather conditions, probably brought about his early demise.

Waqar A Khan is the Founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments