Remembering Rammohun Roy

It is now commonplace to call Rammohun Roy the 'Father of Modern India'; it is much less common to understand or appreciate the historical and ideological content and context of this modernity. But when not understood within the framework of these contexts, this can be no more than a cliché that we mechanically repeat merely to strengthen our presuppositions. Today, as we celebrate the 250th birth anniversary of a gifted individual and visionary, it is only apt that we make a serious effort to understand the prodigious value attached to his life and work, the penetrative nature of his analysis and the very freshness of his vision.

Rammohun's modernity did not lie merely in his location in time. Indeed he was born at a time when the subcontinent was undergoing an important transition in its history, in the very ordering of its social and political experiences. On the other hand, not everybody who was born around the time was blessed with a comparable understanding of his social and political environment as he was. His modernity lay essentially in two things: first, a wide-ranging interest in social and political matters and second, the ability to see the interconnectedness between them. Possibly barring the plastic arts and music, there is very little else that Rammohun did not comment upon. He wholeheartedly engaged with contemporary problems concerning law and the judiciary, freedom of the press, modern agriculture and farming techniques, a reformed religion for the Hindus, gender equality and securing woman's rights over ancestral property, new political theories critiquing absolute rule in favour of republicanism but perhaps above all, restoring the dignity of man and his uniqueness as a creation of God. Rammohun did not categorically choose to make the distinction that we are all expected now to make between the spiritual and the secular. For him life was a creative integration of the two. This would explain his penchant for quite uncharacteristically combining the temporal and transcendental; the spiritual anguish in man as also his ethical responsibility in advancing the material civilization. Rammohun also denied the synthetic divide that we now often make between 'tradition' and 'modernity'. In his protracted battles against his adversaries, who disputed his social and religious ideas, Rammoun consistently took the position that he represented not that which was novel or unprecedented (adhunik), but the innovative face of tradition itself. Presumably he would have been happy to argue that nothing came out of nothing and that even changing ideas in man had to have some foundation in past experiences. Human history, in other words, was not simply about change per se but also intervening stretches of consolidation, stability and continuity. To me this appears to be the very basis of his social, educational and religious programs. His argument was not to introduce ideas or practices that his culture was grossly unfamiliar with; rather, his intention always was to remind his countrymen that they were the victims of a cultural amnesia which had led them to lose the finest of their values or practices to crude and irrational accretions accumulated over the years. The Indic civilization was old, Rammohun reminded his countrymen, and old civilizations tended to acquire a lot of dross and debris in their march through time. It was restoration of its lost ideals that this civilization required, not ill digested innovations found outside one's tradition.

Let us try to understand the underlying idea behind this argument with the aid of some apt examples. First, there was his choice of Vedanta as the philosophical foundation for his enterprise. The enterprise itself was new but the idea behind it, quite old. In associating himself with the Hindu school of Vedanta, Rammohun did not merely act like a revivalist who wished to blindly bring back older ways of life. His reformist mission, on the contrary, was to locate features in the very school of Vedanta that were amenable to modern life. Take for instance Vedanta's disapproval of image worship and the worship of multiple gods and goddesses. Both these suited Rammohun's reformist agenda.

I am willing to hazard the guess that in modern India Rammohun was the first to realize that the worship of multiple deities only promoted sectarian rivalries that had been a recurring feature in our pre-modern past. This he would have also gathered from his early training in Islamic thought and culture which spoke of tauhid or the unity of God. Similarly, to give God some human form not only diluted his very omnipresence and omnipotence but also created a dissipated religious consciousness whereas, ideally, there ought to have been only one that was both strong and sublime. Vedanta. I suggest, he adopted for yet another subtle purpose though this is not very transparent in his writings. The lineage of Sankara Vedanta in which Rammohun situated himself was by nature monistic which is to say that it believed in the oneness of all phenomena. I venture to argue, therefore, that the philosophical unity that Vedanta spoke of, could, in Rammohun's understanding, be easily translated into the political language of Indian unity.

It is no coincidence that Rammohun was the first Indian to have actively used the word Hinduism. The world had known of Hindus but the term Hinduism was quite unheard of until about the late 18th century. What did Rammohun seek to gain by the use of this term? Hitherto, Hinduism was more an orthopraxy than orthodoxy. It paid greater attention to a man's conforming to established social practices rather than a set of fixed doctrines. By using the term 'Hinduism' Rammohun postulated the idea that all Hindus followed a common set of religious practices which was but a stepping stone to their future unity. In 1897, when lecturing at Lahore on the 'common bases of Hinduism', Swami Vivekananda declared that he alone was a Hindu who felt a sense of bonding with a fellow Hindu. This, as one can see, would not have been possible without Rammohun's strategic intervention.

But it would be unwise to see Rammohun purely as a Hindu reformer. There was a cosmopolitan side to him which clearly stands out. In his time, he would have been an outstanding polyglot who knew over a dozen languages and more importantly, used this unique knowledge to gather a deep familiarity with various religious and cultural traditions. Let us recall how his very religious consciousness was shaped by the three major traditions of Islam, Hinduism and Christianity. Even his Muslim friends at the Fort William College, Calcutta, called him a 'zabardust Maulavi'. Rammohun was by birth a Hindu but very Persianized in his sartorial preferences. He was also perhaps the last Hindu scholar of his generation who knew the Muslim just as well as he knew Islam. After him, prominent Hindu figures of the Bengal Renaissance had an understanding of Islam but rarely socialized with Muslims. Rammohun had the courage to admit that Hinduism did not develop the high sense of moral correctness found in Christianity; on the other hand, what he did with Hindu scriptures is comparable to the Lutheran Reformation and perhaps even exceeds it in some respects. The most radical aspect of Rammohun's reform was the attempt to translate Hindu scriptures into the vernacular and even English and to state further that even Sudras and women who had been hitherto denied access to the Hindu canon (shruti), now had access to it. This was indeed a form of religious democracy that the Raja tried to usher and it was this aspect of his work that infuriated the Hindu orthodoxy more than his campaign against sati. Rammohun was not the first to advocate the abolition of sati; he was indeed the first to make Hindu scripture available in the public domain.

In a sense, Rammohun was the true inheritor of Enlightenment rationalism and cosmopolitanism experienced in early modern Europe. He fancied himself as a global citizen whose cry of anguish could relate as much to the English factory hand or the Italian serf as to the Indian peasant. In the 1820s, when the citizens of Naples temporarily freed themselves from Austrian occupation the Raja threw a public dinner in Calcutta to celebrate the occasion. When in England he wished to visit France (whose revolutionary ideals always excited him) and upon hearing that this required an official permit, he wrote of how he had dreamt of a world without borders! Rammohun, along with his friend Dwarkanath Tagore, were champions of free trade but by free trade he did not simply mean the abolition of the Company's monopoly in the India trade but a general freeing of human ideas and aspirations, the soaring of the human spirit. In pleading for the grater colonization of Indian agriculture, he may have misunderstood how this could only make way for the greater colonial penetration of India. But why fault Rammohun when even the santans of Anandamath were forced to concede that the overpowering of the British would be possible only upon matching them in knowledge and strength?

Rammohun was patriotic without being overtly political. He defied the ruling class and the policies they had adopted over several issues that were dear to his heart. The first of these was securing the dignity that the colonial state owed to all its subjects, Indians included. When unjustly insulted by a high-ranking British officer, Sir Frederick Hamilton, Rammohun successfully petitioned the then Governor General and his efforts were suitably rewarded. He shut down one of the several papers he ran in protest against press regulations imposed by the government and mobilized the support of both Hindus and Muslims in protesting the unjust Jury Act which disallowed Indians from judging European offenders.

It might surprise some to hear that Rammohun had something of a pan-Asian consciousness too. When in England he came upon a portrait of Christ which, he alleged, did not depict the true Christ. Wasn't Christ an Asiatic and had the complexion of the Semite, not the Caucasian, he had countered. This anticipated Keshabchandra Sen's famous lecture on "Jesus Christ, Europe and Asia" (1866) and still later, the work of Sister Nivedita and Kakuzo Okakura.

In his deepest thoughts Rammohun Roy was a universalist but a universalist in a special sense. It was his belief that there was a common core to all religious traditions which would emerge once the irrational accretions had been carefully chipped away. Given the common core to all religions, it was possible, Rammohun believed, for all cultures and religious traditions to come together in a common adoration of God. It was in this spirit that the Brahmo Samaj was originally conceived. That this experiment failed to take deeper roots only demonstrates the historical reality that religions are also, on one level, discrete cultures.

Strictly speaking, it would be hard to call Rammohun a secular figure for he appears to have taken religion, albeit only a reformed one, to be the very site of all fundamental changes. Rammohun would not have been averse to the idea of mixing religions with politics but this would be also true of Gandhi whose secular credentials cannot be doubted. I am inclined to think that like Gandhi, Rammohun could sense and he sensed this rather early, that nothing moved Indians the way religion did. He anticipates Gandhi again in his eclectic respect for all cultures, his underlying faith in the potential of man for transforming himself.

Rammohun's Hinduism could not have relapsed into 'Hindutva' or a crude political Hinduism. For him the defining quality of the Indic civilization was its plurality and the ability to build bridges of understanding across deep chasms of difference. At the same time, his deep engagement with religion and faith in its liberating and transformative aspects, could disabuse us of the view, now very popular with some, that religions breed only acrimony, violence and intolerance. Rammohun himself never confused selfless spirituality with self-seeking religion.

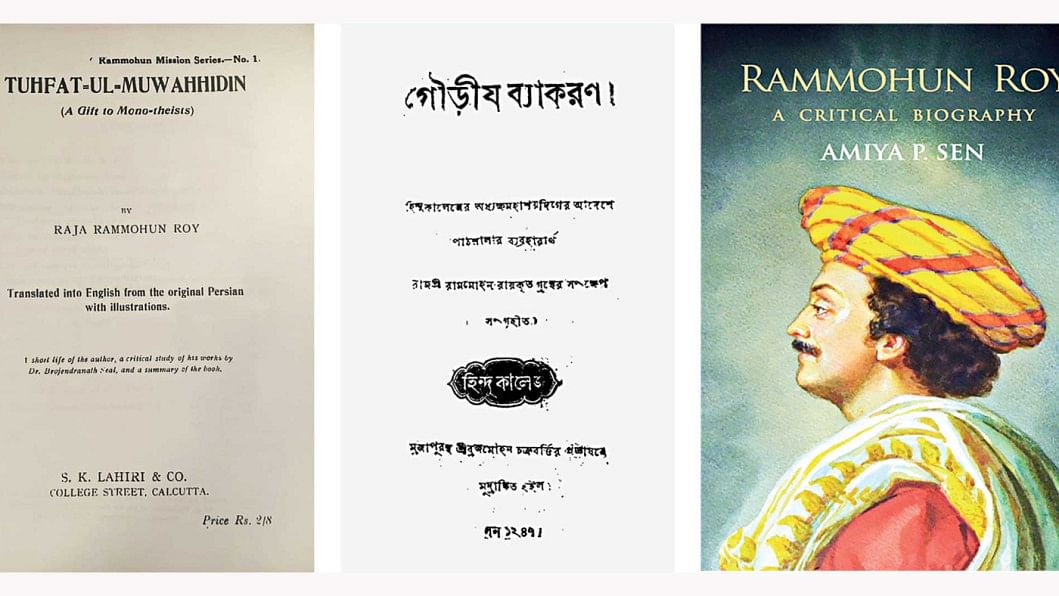

Amiya P. Sen is an author and historian. He has written several books including Rammohun Roy: A critical biography (Penguin, 2012)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments