Revisiting the Bengal Famine of 1943

The 1930s in Bengal were devastating for the poor. Global depression since 1929 had disabled the economy, and across the province there was ample evidence of starvation. The long trajectory of the colonial occupation of Bengal had begun with catastrophic famine in 1770, with as much as one third of the population of the province annihilated by starvation at the very advent of British conquest. Thereafter, the British East India Company continued its ruthless dismantling of the remaining economy, looting the province for fantastic profit, decimating native manufacture, and turning Bengal into a European plantation - with the accident of a population of 60 million people. The Crown, after taking over in 1858, did little better. At the height of Victorian splendor, by the late 19th century, 60-70 million people had been annihilated through starvation in British India. The record of British rule in the 20th century proved similarly checkered.

In the wake of World War I, the price of agricultural commodities collapsed, credit dried up completely, and destitution and despair were widespread, particularly in the eastern districts of Bengal. The index price of jute, set at 100 in 1914, had collapsed a full 60% by 1934. Satish Chandra Mitter in his Recovery Plan for Bengal, written that same year, warned: "it is evident to anyone familiar with agricultural conditions...and with the lives of the cultivators...that they exist rather than live, and that the margin between starvation and existence is an extremely small one." [Mitter, S.C. A Recovery Plan for Bengal. (Calcutta: The Book Company, 1934) p. 42.] Agricultural laborers had been driven to abject destitution, malaria was decimating the province every winter, the fisheries were in ruins, cottage industries were bankrupt, and flood control was non-existent -- so much for the civilizational mission of colonialism, 180 years later! In 1937 populist leader of the Krishak Praja Party, Fazlul Huq, ran his campaign on the central platform of "Dal-Bhat;" and on that platform became the first Bengali Prime Minister of Bengal under British rule.

During this same period, jute cultivation, and the jute industry at large, were increasingly coming under the domination of Indian capital. In response to the jute industry's woes of the 1920s and 1930s, these agro-industrial interests, many hailing from outside of Bengal, diversified into coal, commodity markets, rice milling, and eventually textile production. When war was declared on Germany on September 3rd, 1939, these same interests were well positioned to make the best of bad times. It was clear from the outset of the war that loot of the colonies would be a central pathway to victory. Raw goods, natural resources, territorial outposts, soldiers, labor, industrial output, munitions - Britain would need it all. In order to harness India to the war effort, moreover, it was also necessary to impress the hysteria of Empire in Crisis onto a subjected and starving population. A din of wartime propaganda was decimated from Calcutta, just as industrial capacities were quickly scaled up.

As industrial production was scaled up; labor needs soared, industrial wages increased, and the city of Calcutta, in particular, began to boom. Supplying the Allied war effort proved lucrative business for European and Indian industrialists alike. War production was named an "essential" industry, and labor and foodstuff costs could be written off against an Excess Profits Tax, that was meant to curb skyrocketing profits. Wage work by migrant populations laboring in Calcutta could support whole clans in destitute villages left behind, but in the majority of the 90,000 villages of occupied Bengal, bare survival remained the order of the day. After the long decades of slumping prices and deepening destitution, the declaration of war meant very little to the vast majority. Many had only heard of "the war" peripherally, if at all. Meanwhile, due to the macro-economic boom, the price of rice had risen 33% by October of 1940, and reports of famine in Midnapur, Birbhum, Bankura and Murshidabad were printed in Calcutta newspapers. By October of 1941, the price of rice had increased an additional 36%, and starvation was reported in Noakhali and Tripura. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.

When Japan drove Britain out of Burma in the first few months 1942, that pendulum swung still further. Bengal was now on the very front of war with Japan, and its importance strategically, logistically and industrially multiplied. In the name of protecting Bengal from potential Japanese invasion, a scorched earth campaign was undertaken from Chittagong to coastal Midnapur. Special Officer L.G. Pinnell was sent from Delhi to oversee what came to be known as the "Denial Scheme". Denial involved three main components: the removal of tens of thousands of villagers from their lands (in order to build a defense corridor around Calcutta, and airstrips in eastern Bengal), the disabling and destruction of 45,000 "country-boats" (shattering the transportation infrastructure of deltaic Bengal) and the appropriation of all "excess rice" in that same region (ostensibly to "deny" Japan resources they might commandeer in the event of invasion.) By August of 1942, the Prime Minister of Bengal, Fazlul Huq was warning the imperial Governor in no uncertain terms that there was a "rice famine in Bengal". Between July 7th and August 21st, alone, the price of rice in the province had risen by 65%.

The question of how much rice was removed from districts during the Denial Scheme is difficult to answer, but the impacts of Denial were far-reaching. In terms of rice markets, and in relation to mass casualties due to starvation yet to come, perhaps the most significant aspect of the scheme was the partnering of the colonial government, martial authority and industrial interests in the name of removing rice from the countryside to Calcutta. Contracts for Denial were given to large-scale commercial agents from Calcutta, who had little knowledge about local market structures. They were backed in their efforts by imperial authority, accompanied by armed guard and given wide powers at purchasing, and even confiscating, rice. Apart from the tons of rice thus removed from local holding, local markets were destroyed by such heavy-handedness and a general panic gripped the countryside. The various chambers of commerce of Bengal, meanwhile, joined forces and made large purchases on their members' accounts, operating "unofficially" under the auspices of Denial, even while Calcutta industrial firms continued purchasing on their own as well. This triumvirate of forces - governmental, martial and industrial -- would rule resources and markets for the duration of the war.

The mantra of feeding industrial Calcutta had quickly become synonymous with the war effort at large. Textile mills all along the Hooghly river were operating at full capacity, troops from the farthest reaches of the British Empire and America were pouring into Calcutta, and heavy industrial manufacturing was booming. And as the draw of Calcutta, both economically and demographically, had exploded, just as quickly, conditions in the countryside deteriorated. Ceiling prices on rice were fixed, and then repeatedly undermined by corporate purchases above that ceiling rate. Black markets flourished and essential goods across the board became scarcer and scarcer on open markets. When a devastating cyclone hit Midnapur in October of 1942, the relief officer was told to go purchase relief grain on the open market in Calcutta -- government had nothing in hand to spare, even while Denial rice was funneling into corporate go-downs. Collective fines, meanwhile, were levied across the province to keep a restive population from open revolt. Meanwhile, all costs related to the "war effort" were being borne by the Government of India, and written off by the Crown as an IOU in the form of "Sterling Balances". Throughout the war, rupees continued flying of the printing presses, pouring gasoline on the fire of war-time inflation.

When Calcutta was bombed by Japanese aircraft in December of 1942, the situation deteriorated further. A significant segment of Indian commercial interests operating in Calcutta were from outside the province. When bombs began to fall, these non-Bengali business houses shuttered their warehouses and fled the province. The colonial government, again under the direction of L.G. Pinnell in Bengal, broke into the shuttered rice warehouses of these same interests to ensure their own access to stockpiles. The compensation given to stockists was below prevailing market rates, and a deep wedge was driven between government and Indian commercial interests in Calcutta. This had reverberations, also, in the Rice Mills Association which had overlapping membership with industrial interests more widely. Many mills shut down in protest of government heavy-handedness and the nexus of cooperation between Capital and the colonial state was strained. In addition, more rice went "underground," unreported to governmental authority, either hoarded against continuing inflation or making its way into black markets.

Although 90% of rice consumed in Bengal was hand-milled locally, commercially milled rice ("polished rice" as it was called) was crucial to feeding Calcutta, and particularly its industrial, military and white-collar workforce. Bottle necks in rice mills created shortage in the city, and that shortage began to breed real panic in administrative circles. Government, again employing commercial agents and backed by military fiat, fanned out into the countryside and began beating the bushes to unearth "hoards" of rice. Whatever they could squeeze out of local markets - much of the time through coercive measure - received priority transport arrangements in its passage to Calcutta. The winter harvest was in, and the greed for rice in Calcutta knew few bounds. Prices across the countryside went far out of the reach of the rural majority and starvation escalated precipitately, with agricultural laborers too poor to retain even a subsistence share of their own production. Millions of Bengali villagers were on the precipice of mass starvation.

In March of 1943, the elected government of Fazlul Huq was duped into resignation by the colonial government, and Emergency Rule was declared in Bengal. The Governor behind the conspiracy to oust Huq, retired to Darjeeling shortly thereafter and spent the rest of his career as governor dying in the hills, while Bengal starved. A "Food Drive" was called, and shortly thereafter a food "Census". Both campaigns, again, saw colonial government partnering with private trade to fleece remaining rice supplies out of the districts of Bengal. Looting of paddy was prevented by military escort and any "census" of holdings in Calcutta was forestalled. By this time, the Viceroy was sending increasingly alarming reports to the Secretary of State in London about the "food situation" in India. An influx of food grains released on open markets would be the only thing likely to break the inflationary spiral that was fueling starvation and wider despair. Repeatedly, during the next many months, Winston Churchill, presiding over the War Cabinet in London, single-handedly vetoed all motions for imports.

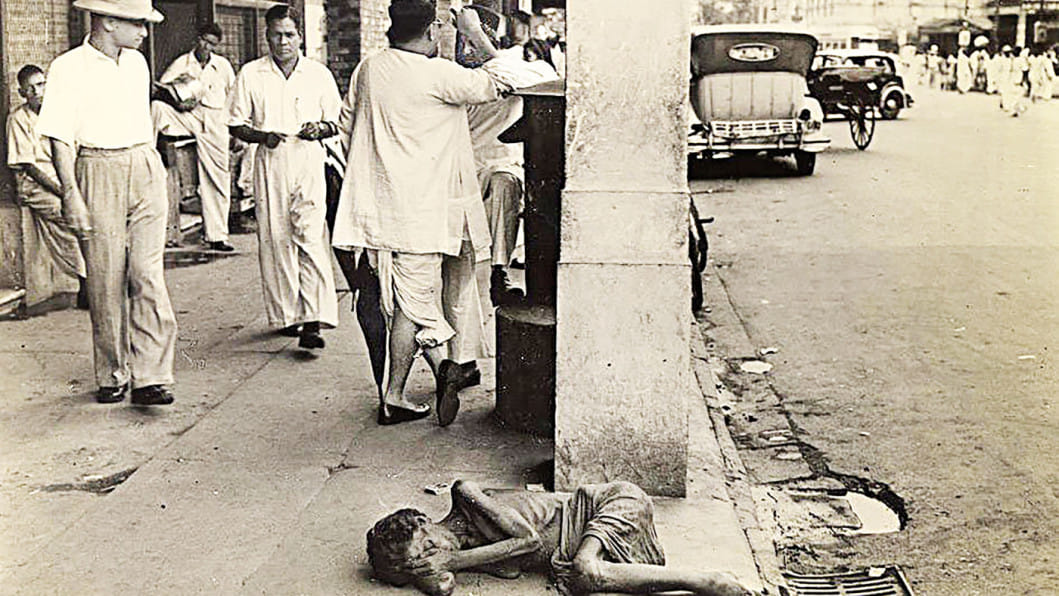

In Bengal, millions were starving to death, and tens of millions were on the move, seeking bare survival. Bodies began piling up on roadsides and in ponds, rivers and ditches. Vultures got too fat to take flight, and jackals feasted on still-living bodies in broad daylight. The spectacle of famine also erupted on the streets of Calcutta, and vaulted into international news. Japan and Germany both made hay of starvation in the Second City of Empire. The streets of Calcutta became haunted by round ups and deportations. In famine camps only starvation rations were given. Over the course of the next three years between 3 and 6 million people died of starvation and its related diseases in Bengal. The countryside lay in utter ruins. Meanwhile, India had been industrialized in the heat of war - and in the shadow of famine. But in the conflagration of all that was to come, famine itself faded into the shadows of independence and partition.

In much of my historical work, I have argued against this erasure of famine from analysis of the political economy of pre-partition Bengal. The Bengal Famine of 1943 (as it has come to be called) is a revealing lens through which to view the dynamics of power and disempowerment. privilege and inequality - and life and death itself - at a critical juncture in the history of Bengal. Famine was no anomaly, either economically or societally; it was the crystallization of prevailing structures of power and disempowerment amplified by the "crisis" of war. Trajectories of power reach climax in events like famine, and war. Divisions of human life become concretized in mass death. Question of belonging and abandonment, collective grief and collective callousness, class, community, family; all go into sharp revolution during famine, and politics often follow suit.

With a cobbled together Muslim League ministry in Bengal bootstrapped into power in the spring of 1943, provincial politics became increasingly entrenched in communal rancor. The political context of the province had already become laden with the weight of hundreds of thousands of destroyed bodies, many millions were yet to follow. Shyama Prasad Mookerjee promised problems for a Ministry opposed "by the entire Hindu community,"[ The Statesman, "Dr. Mookerjee's Views," April 27, 1943] and communally driven accusations and counter-accusation related to famine dominated the political landscape. As starvation deaths mounted, the tenor of provincial politics became only that much more dark and elemental. Rumors that the Muslim League government was giving differential relief to Muslims were countered by charges that organizations like the Hindu Mahasabha were giving relief only to Hindus. Rationing was meanwhile long delayed by "communal quotas", and opposition parties did all they could to thwart government efforts to gain control of supply so that they might bring down prices.

To write famine out of the deteriorating communal situation in Bengal in the lead up to partition is a naive historical exercise. It is well understood that acute economic crisis, particularly when embedded in already divisive electoral politics, often engenders a hardening of positions and identities. Resentment, fear and despair become operative principles in political debate. Promises of remedy, and accusations of blame, become electoral platforms. This is well understood to be the case, for instance, in post-WWI European history, with the rise of authoritarianism and fascism almost universally connected to the hyper-inflation and economic displacement of the 1920s. But in the far graver economic crisis of famine in Bengal - where it was not merely a question of livelihoods, but of human life itself - there is something of a squeamishness about taking famine seriously in terms of its socio-political impacts. But historical evidence of what role famine played in the political economy of 1940s Bengal is abundant. The structures of power, voice and political agency that were forged in the context of famine have profound implications, even today.

The Bengal Famine of 1943 also impacted Bengali culture in profound ways. Famine in Bengal triggered what might be called a creative revolution as well. By 1944, artists like Chittaprosad and Zainul Abedin were pioneering new forms of social realism out of the depths of famine despair. Their depictions of suffering Bengal remain iconic even to younger generations. The Indian Peoples' Theater Association also began touring the country, staging public dramas, again revolving around hunger and inequality. Poetry, literature, sculpture, photography - the aesthetics, and ethics, of capturing the monstruous injustice of famine dictated creative practice in Bengal for decades to come. And in more intimate spaces, in the domestic sphere, stories about the witness of famine in Bengal have spanned many generations, and represent a deep existential root in families. Grandparents, and now great-grandparents have been telling, and re-telling: the sorrow of death on that scale, the bodies discarded, the fat vultures, indignation at the injustice of it all. The impact of the inter-generational memory of the holocaust of famine in Bengal is immense. The stories that have been passed down about famine also often carry a moral tenor that is meant to instruct on questions like greed, charity, mercy and grief.

But with millions dead and tens of millions uprooted by abject material deprivation, it is difficult to gauge the priorities of the masses at the margins during these same years. Mass death continued throughout 1944, and starvation and disease ravaged Bengal well into 1946. The 1945-46 winter rice crop had been poor, and famine delegations were touring the province that summer. Then, in August of 1946 cataclysmic violence erupted on the streets of Calcutta, and a cascade of communal violence across colonial India followed. In Bengal, communal politics, now steeped in so much blood, hardened and intensified. Then, exactly a year after the Great Calcutta Killings, came independence and the partition of British India. In the heat of all that unfolded in this single year, famine may have been pushed into the shadows; but famine, it might be said - with all its myriad associations and historical implications - represents the last un-partitioned collective memory of the Bengali people.

Janam Mukherjee is a Professor of History at Ryerson University, Toronto

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments