The day we made a tryst with destiny!

Amar Ekushey (Immortal 21 February) is a day of special significance for us in Bangladesh, as we recall with reverence and gratitude, all those young brave-hearts who made supreme sacrifice by giving up their youthful lives for a noble cause.

Their cardinal example of obligatory renunciation of life, finally culminated in our ultimate emancipation as a Bengali nation through our glorious Liberation War in 1971.

Now seventy years on, that soul-searing pain comes alive to remind us once more through that melancholic, heart-wrenching, devotional song immortalized by Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury's hauntingly melodious dirge "Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Ragano Ekushey Februari, Aami Ki Bhulite Pari" ("My brothers incarnadine blood spattered 21 February, how can I ever forget") as it continued to reverberate throughout the country and beyond, with the advent of dawn on 21 February, 2022. It's up to us now, especially, the younger generations in this country to uphold those sacred vows for which the Ekushey martyrs gave their young lives so selflessly, defiantly and bravely facing live bullets 70 years ago. They are the pride of the nation along with all those indomitable heroes and martyrs of our great liberation war, both known and unknown, in 1971.

Let us briefly recapitulate the historical context that led to 'Ekushey': The British left in shameful haste, recklessly dividing British India into the dominions of India and Pakistan in 1947. Our leaders kowtowed and acquiesced to it. Besides, events had moved very fast indeed, the momentum of which simply overwhelmed the then Indian leadership (Congress and League). By then they were elderly men, exhausted and to be frank - had little choice. The British had dictated the ultimatum: Now or Never! The so-called British lion, 'emasculated' by WWII, the daring exploits of the INA under Netaji Subhas Bose and huge financial debt to USA, was a spent force. As a retreating imperialist power 'they simply didn't care'. That's what imperialist are won't to do when their game is up! Therefore, they were determined to leave India posthaste. Furthermore, the British had tired of the endless acrimonious politicking of the Congress and the League, which was the fallout of their own avowed colonial dictum: `Divide et Impera', or 'Divide and Rule' policy, which they had assiduously cultivated for their own nefarious interest in the aftermath of 1857, by successfully polarizing the two principal communities, Hindus and Muslims. It had naturally resulted in a great psychological divide and, pitted the two communities slowly but surely into two acrimonious camps, to which the leaders of both the sides unwittingly contributed. Thus, in 1947 Pakistan emerged as an improbable nation-state based on a bogus 'Two-Nation Theory' amidst the ensuing confusion. The British had also by cunning design gifted Jinnah with a truncated "moth-eaten Pakistan" for his unstinted support to the Raj during WWII, while keeping a wary eye on the West's geo-political exigency as it arose at the advent of the Cold War following WWII. Thus, Pakistan came to comprise lands to the extreme West (recall the perceived Soviet threat from across the Durrand Line along the Hindu Kush) and East ends (now Bangladesh) of the former British Indian Empire, separated by a thousand miles of Indian territory in the midst.

In the late 1970s, I had once vigorously taken on an English acquaintance at a London pub, when the inevitable topic of the Partition of 1947, and its disastrous consequences in 1971, came up during our conversation. The Briton was a history graduate from Cambridge. Unlike today, there was very little declassified information available on the Partition of British India in those days. Besides, almost all available books on the fateful partition were mostly written by Britons from their own viewpoint. Even the notable American historian, academic and writer on South Asia, Stanley Wolpert's preeminently readable slim volume 'Shameful Flight: The Last Days of the British Indian Empire' (2006) on the fateful partition was still a thing into the future, let alone a wealth of well-researched, scholarly works published in the last 30 years alone from various credible sources. At the pub, I had endlessly castigated the soft spoken Englishman for the precipitous and ill-planned partition of British India by the retreating Raj. He had listened to my fulsome diatribes with equanimous patience. As I paused to catch my breath, he raised his hand, smiled while adjusting his spectacles, affected the demeanor of a barrister and took me on with a flourish, "Well, Mr. Khan you seem to have missed the moot point altogether?" he said with a chuckle and added with a sheepish grin, "You quite forget that the English are essentially a nation of shopkeepers. So, one fine morning we took a good look at our ledger and it simply did not add up to anything substantial, anymore. So, we closed shop (read British India) gave you what you 'deserved', handed over the keys to you and sailed for sweet home. That's what a clever 'baniya' does, isn't it?" His wry British humor, sharp intellect and incisive retort jarred me before the gist of it sank in. After a second's pause, we had burst into laughter, ordered a further round of beer and, drank to each other's health in good cheer. The man had indeed deftly summarized it all in a nutshell.

From the mid-19th century in British India, an idea had slowly developed particularly within the elite classes of Muslims, foremost in upper India, that is, in the Delhi belt, United Provinces, Deccan (Hyderabad) and Bihar comprising of the Muslim feudal gentry, aristocracy and educationists like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan of the Aligarh fame, that Urdu the Perso-Arabic scripted language was the sole 'lingua franca' of the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent. A great, noble religion like Islam was most unnecessarily tagged along with this idea to appeal to the primordial sentiments of the faithful. Thus, the dye was cast and it took shape in the public imagination. In the concept of Pakistan as espoused by Choudhry Rahmat Ali an Indian Muslim student in London, East Bengal with a large majority of Muslim population, did not even feature in his scheme of things. I once saw a British era map of East Bengal, perhaps drawn up by an uncouth, over- zealous upper Indian Muslim where East Bengal is referred to with a derogatory pre-fix of 'Bang-i-Islam', a derisive nomenclature, as if, the Muslims of East Bengal were not Muslim enough! I was swept with revulsion on seeing this map.

With the establishment of Pakistan Urdu was unequivocally declared by Jinnah as the only state language to facilitate national integration, regardless of the fact that except for the educated elite, only three percent of the population in the new country were proficient in it. Besides, Urdu was an alien language in the then East Bengal (now Bangladesh) who spoke in their own mother tongue Bangla and, moreover democratically constituted 54 percent of the national population of the country. Therefore, it was perceived correctly by the proud Bengalis as an outright imposition and a denial of their fundamental rights. Besides, it smacked of linguistic and cultural annihilation! However, when Jinnah as the governor general visited Dhaka for the first and last time he categorically stated the same to the face of protestation and arguments of the Bengali students, politicians and intellectuals. Having flown back to Karachi, Jinnah, once gain reiterated his steadfast resolve on the issue. He did not heed the polite, logical arguments nor protestations that emanated from East Bengal. Thus, it can be persuasively argued that the intransigence of the creator of Pakistan ignited the first spark that lead to the 'beginning of the end of Pakistan' as it had emerged in 1947, finally leading to the conflagration in 1971, with the brutal genocide unleashed by the Pakistani oligarchy and military junta and the birth of Bangladesh. So, the political fissures were manifest from the very inception of Pakistan, from 1947-'48 onwards. After Jinnah's death in 1948, the ineffectual leader Khawaja Nazimuddin as the next governor-general repeated the same mistake leading to virulent agitation in Dhaka. He retracted and came to an interim understanding on the issue. However, the dye was cast! The vociferous agitation of students, politicians and the general public on the streets of Dhaka, ultimately led to the embracement of martyrdom by students and some in the public on 21 February, 1952. Finally, after much ado, that is, through continuous agitation and further loss of life on Dhaka streets, the Pakistan government was forced under the circumstances to recognize Bangla as one of the two national languages of the state of Pakistan on 21 February, 1956.

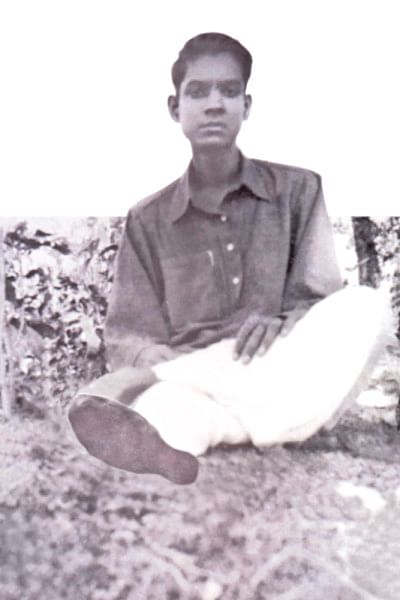

In this article while paying befitting tributes to all the Shaheed's (Martyrs) of our Language movement, that is, on 21 February 1952, I shall focus on Shaheed Abul Barkat in particular because of our long family connection with his immediate family members since 1950, before my birth. Both our families had migrated from West Bengal and domiciled in the then East Bengal following the Partition of 1947. Besides, our families were next door neighbors in Purana Paltan in Dhaka. Hailing from Murshidadbad (Barkat) and Malda (my family) there developed a close bond between us. Abul Barkat was like a family member and well known to my parents, aunts and uncles. He went to the fateful rally on 21 February from the house of his maternal uncle, adjacent to the house of my close relative, never to return and embraced martyrdom. I am able to share a few rare photographs due to my long ties with Barkat's first cousin, my childhood friend Yousuf Reza and his nephew Ayenuddin Barkat. I remain grateful for their help and cooperation.

Abul Barkat was born in June 16, 1927 in his ancestral home in the village of Babla, Salar, Murshidabad, West Bengal (see Fig 01). He studied in Babla primary school and passed his matriculation from Talibur High School in 1945, and completed his intermediate from Krishnath College in 1947. He moved to Dhaka in 1948, a year after partition to live with his maternal uncle in Purana Paltan, Dhaka and completed his Bachelors degree in Political Science from Dhaka University in 1951. He continued with his Masters degree in Dhaka University. On 21 February, 1952, students and the public brought out a procession demanding that Bengali language be recognized and given the status of a state language along with Urdu in Pakistan. Despite the imposition of Section 144 (curfew) and a ban on rallies, the Bengalis defiantly continued with their protest march and, was indiscriminately fired upon by the police and army in front of the Dhaka Medical College. Abul Barkat sustained a grievous bullet wound and later died at the Dhaka Medical College hospital around 8pm on 21 February. He was stealthily buried in the darkness of the same night at the Azimpur graveyard under strict police escort.

Postscript: Today, we recall with great pride that the ethos of our 'Immortal 21 February' is observed globally, due to the exemplary diplomatic initiatives of Bangladesh. The world has recognized the essence of the tragic event of 21 February, 1952, and declared it as the 'International Mother Language Day'! It is now annually commemorated worldwide with due solemnity to promote awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity and to encourage multilingualism. This important decision was first announced by UNESCO on 17 November 1999, and formally endorsed and recognized by the United National General Assembly with the adoption of a UN resolution in 2002. It is unique in the history of the world that Bangladesh is the only country which has paid a price in 'blood' for the right to speak its own mother tongue, Bangla!

Waqar A Khan is the Founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments