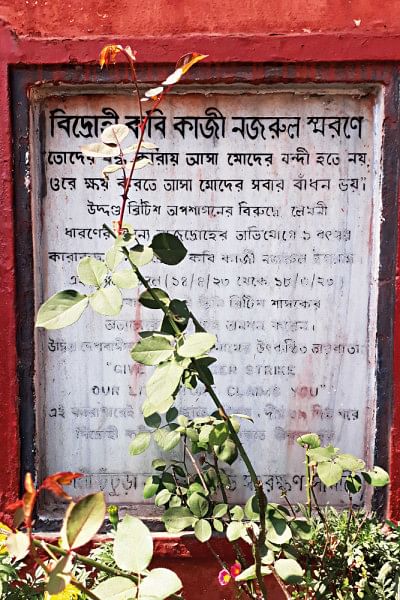

Nazrul, the eternal rebel warrior: 100 years later

One late December night in 1921, Kazi Nazrul Islam wrote what would be his most iconoclastic poem, the poem that would give rise to his soubriquet, "Bidrohi Kabi," the Rebel Poet. Inspired by a complex of emotions, Nazrul's ideas were flowing too fast for his pen to keep pace. This is why, according to Muzzafar Ahmed in Kazi Nazrul Islam: Smritikatha, the poet first wrote the poem in pencil so that he did not have to continuously dip his pen in the inkpot. The poem combined his Muslim heritage with his knowledge of Hindu mythology, his anger against repression and discrimination, his love for a young teenage girl, and his experience as a soldier in the British Indian army.

Early next morning, Nazrul read out the poem to Muzzafar Ahmed. His friend did not show the enthusiasm that the poet had expected. However, others realized the importance of the poem, and "Bidrohi" appeared in Bijli on 22 Poush 1328 [January 6, 1922].

Nazrul's writings were being printed in Kolkata magazines and he was moving in literary circles, but nothing that he had written before compared with this poem. A new writer had emerged, and someone very different from Gurudev. That a child born in impoverished conditions in Churulia would grow up to write poetry, songs, fiction, political editorials, speeches and become the national poet of Bangladesh should have been impossible. But all these things did happen. As a child, growing up near a mosque, going to school in a maktab, often doing odd jobs in the mosque, his life should have been like that of countless villagers who die unknown and unsung. Or, introduced to the life of itinerant leto groups where he learned about Hindu myths and legends, he could have turned into a vagabond. But something happened to transform his life.

As Professor Rafiqul Islam points out in Biography of Kazi Nazrul Islam, the most important event in the life of a young man who was forced to earn a living from a tender age, whose schooling was only sporadic, was his enlisting in the 49th Bengali Regiment. Posted at Karachi, he was exposed to what he would never have known in Churulia or in the small towns to which his restless nature took him. In Karachi, for the first time he not only got a regular salary which enabled him to subscribe to magazines from Kolkata, but also, despite the parades and marches, enough spare time to write. He proudly wrote "havildar" before his name when he wrote to editors in Kolkata. He had learned Arabic as a young boy, now he learned Persian with the Punjabi moulvi of the regiment, well enough to translate Omar Khayyam and Hafiz. He read about Communism and the Russian Revolution. He heard about the events taking place in the Middle East and the rise of Kemal Pasha.

The poems "Kemal Pasha," "Ronobheri," "Bajichhe Damama" and "Shat-el Arab" reflect a Pan-Islamic influence. In "Shat-el-Arab," for example, he draws upon the history of the glorious Muslim past. But at the time that Nazrul was writing, Arabia was as subjugated as India was. There is thus an elegiac note in the poem. However, not just satisfied with bemoaning a lost past, in "Bajichhe Damama" the poet gives a call to battle to restore the lost glory of Islam.

Though Nazrul would go on to write many devotional poems, in "Bidrohi" he celebrated the rebel as a superman whose head did not bow before any deity. The opening lines of the poem were unlike any written at the time: Bolo bir/Bolo unnato momo shir/Shir nehari amari, notoshir oi shikhor himadrir [Speak, Hero, say,/ My head is held high,/At its sight the Himalayan peak hangs down its head]. The effect of the alliteration, the internal rhymes and the declamatory note of the poem is almost impossible to translate into English verse. Like Walt Whitman – with whom Nazrul has been compared by scholars such as Syed Ali Ahsan – the poet is celebrating himself. In the 139-line poem, 98 of the lines begin with "ami" [I]. The word is also repeated 47 times within the lines of the poem. The words "momo" [my] and "amari" [mine] are also strewn throughout the poem. But while the poet celebrates himself, he is also celebrating the superman who can defy all forces. In fact, Nazrul begins by addressing a "bir," a warrior, before slipping into "ami."

The poet Mohitlal Majumdar accused Nazrul of plagiarizing from his essay "Ami" [I] which he had read out to Nazrul and Muzaffar Ahmed at the Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samity in 1920. While it is possible that Majumdar's essay might have been in the back of Nazrul's mind while he was composing the poem, Majumdar's essay does not have the complex of images and associations of Nazrul's poem. It is even more possible that it was Rabindranath Tagore's poem "Prarthona" from Naivedya which inspired Nazrul. The first line of Tagore's poem reads "Chitto jetha bhayshunno, uchcho jetha shir," and, in his own English translation, "Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high." The poem, whether read in the Bangla original or in Rabindranath's own English translation, is a prayer to the Creator.

Nazrul, who had read much of Rabindranath – and often quoted him in his writings and in Bandhon Hara has a character refer to the older poet's Nobel Prize – could not have been unaware of this poem. However, Nazrul's "Bidrohi" is significantly different from Rabindranath's "Prarthona" as well as from Majumdar's "Ami." "Rabindranath's poem is a prayer, Nazrul's a call to arms and action." The difference in tone is similar to the difference between Rabindranath's "Esho, esho, esho he baishakh" and Nazrul's "Proloyullash." Rabindranath prays for the Baishakhi storm to wash away all the accumulated rubbish of the past year, while Nazrul welcomes the violence of destruction which is also the turbulence of creation.

What does the word "bir" in the first line of the poem mean? It is both an adjective and a noun, meaning "brave" and "soldier" respectively. Different translators of the poem have translated the word differently. Kabir Chowdhury uses the adjective "valiant" as a noun; Syed Sajjad Husain, Abdul Hakim, Sajed Kamal and Kaiser Haq all use "hero." Bir, however, has a significant association with warrior. In his translation of "Shat el Arab," Syed Sajjad Husain had translated the word "bir" in the second line of the poem as "fighters." In "Bidrohi," while the soldier poet had become the rebel poet, the soldier is still there. In fact, the poem is unique in the way it blends the soldier and the rebel with the lover.

In line 49 of the poem, the poet juxtaposes love and destruction by referring to the different musical instruments of love and war: "Momo ek hate banka bansher banshori, aar hate rono turjo" [In one hand I hold the tender bamboo flute, / The trumpet of war in the other]. Both the flute and the trumpet are musical instruments, but vastly different from each other in sound and symbolism. The trumpet is associated with war, the flute with love. Strangely, the poet describes the flute as "banka." A flute cannot be crooked and still be played upon. This image suggests the "tribhanga" pose of Krishna, the flute player, the lover of Radha.

While the title, "Bidrohi," means "Rebel," and the main theme of the poem is about shattering all forms of oppression and discrimination – secular, political, societal, religious – the poem is also celebratory. It eulogizes man's humanity, his creativity, his ability to withstand pain, as well as his ability to love and to savour the beauty of life and nature. It combines destruction with creation.

I am the rainstorm, the hurricane,

Smashing all in its path.

I am the dance-crazy rhythm,

Dancing to my own beats.

I am the joy of a life of total freedom.

Nazrul would write both Hindu devotional songs as well as hamds in praise of Allah and naats in praise of the Prophet. He would write about Fateha Doazdahum, about Moharram, about the two Eids, about the different obligations of a Muslim. He would write both kirtan and shyama sangeet. Before 1971, there was an attempt to make Nazrul an Islamic poet. "Hindu" words were changed to "Islamic" ones; words, phrases and stanzas were omitted. But Nazrul wasn't an Islamic poet. Married to Ashalata Sengupta, whom he renamed Pramila, he named his sons a combination of Hindu and Muslim names. And, in his poems on socialism, he talks about a world where all religions coexist peacefully. In "Samyabadi," translated by Sajed Kamal as "I Sing of Equality," Nazrul embraces four major religions. But he also points out that it is not important to be a devout Hindu, Christian, Buddhist or Muslim. True religion lies in the human heart.

In "Bidrohi" Nazrul is an iconoclast. He wants to rise above God's throne, he wants to stamp his footprint on the bosom of God. Early translators omitted lines that seemed sacrilegious. In his translation of "Bidrohi," Kabir Chowdhury, for example, ends on these beautiful lines:

Weary of struggle, I, the great rebel,

Shall rest in quiet only when I find

The sky and the air free of the piteous groans of the oppressed.

Only when the battlefields are cleared of jingling bloody sabres

Shall I, weary of struggles, rest in quiet,

I, the great rebel.

I am the rebel eternal,

I raise my head beyond this world,

High, ever erect and alone.

However, before the last three lines which end Professor Chowdhury's translation of "Bidrohi," there is an omission of four important lines. Syed Sajjad Husain, who also translated this poem, conflates the missing lines with the last three lines in this translation:

I am the implacable foe

Of cruel blind Destiny

Which rules the universe,

The whimsical despotic deity whom I despise,

I the eternal rebel who never submits.

What were the lines that both the translators omitted/glossed over?

In Sajed Kamal's translation they read:

I'm the Rebel Bhrigu,

I'll stamp my footprints on the chest of god

Sleeping away indifferently, whimsically,

While the creation is suffering.

I'm the Rebel Bhrigu,

I'll stamp my footprints –

I'll tear apart the chest of the whimsical god.

Abdul Hakim too translates the lines but is careful to note that the poet is not referring to the Muslim Allah but to Bhagawan.

Juxtaposing the rebellious note in the poem and the violent images – "Ami bhora-tori kori bhora-dubi, ami torpedo, ami bhim bhasoman mine" [I sink the cargo-laden boat;/ I am a torpedo, a deadly floating mine] – are images of loveliness, beauty, tenderness. Why, in a poem celebrating rebellion, are there love notes? Ghulam Murshid, in Bidrohi Ranaklanta, suggests that at the time of writing this poem, the poet was also a lover. The detailed images of young love seem out of place in the poem unless one understands that the poet had fallen in love with Ashalata Sengupta, a Brahmo girl. By falling in love with a girl outside his religious community, the poet was also rebelling against the dictates of a conventional society which would keep lovers from different communities apart.

Understanding this background helps explain why, along with the description of the forces of destruction, the poet describes the beauty of woman and the passion of young love.

I am the fancy-free maiden's flowing hair, the glow in her eyes,

The fiery passion in the lotus-heart of a sixteen-year-old girl.

A few lines later, the poet describes the ways of love at a time when social conventions did not allow young men and women to mix before marriage:

I am the tremulous excitement of a girl's first stolen kiss;

I am the quick sidelong glance of a secret lover;

I am a young girl's romance, the tinkle of her glass bangles.

However, love and romance are only part of the multitudinous variety of this poem which ends on the same note of rebellion with which it begins, with the poet declaring his defiance of the divine, his rebellion against conventional religion: Ami chiro bidrohi bir/ Bishwa chharaye uthiyachhi eka chiro-unnato shir" [I am the eternal rebel hero –/Alone, my head ever high,/Rising far above Earth].

Note: Except where specified, all translations of "Bidrohi" are by Kaiser Haq.

Niaz Zaman, Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh, is a writer and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments