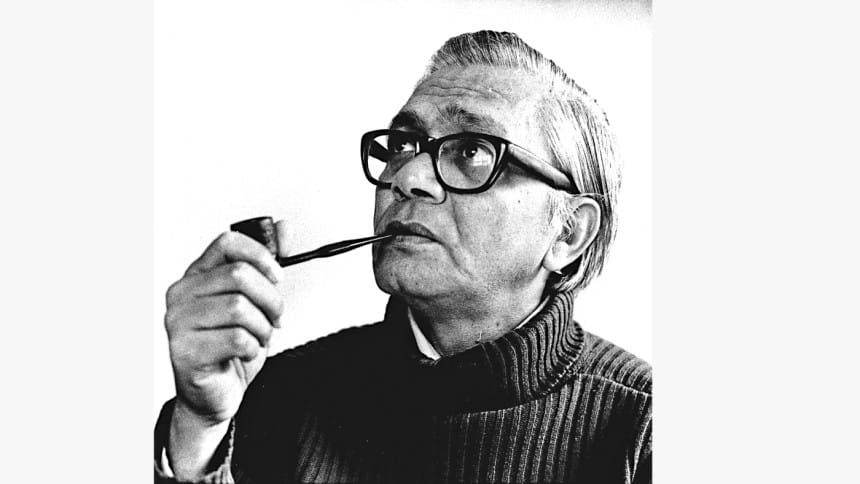

The indefatigable public intellectual and political mobiliser

A small incident took place at a school in Burdwan in 1944. A class teacher of Grade 7 was wrongly reprimanding a student, accusing him of stacking all the high benches of the classroom against the short ones the previous evening, when a lanky boy stood up and said, "It was not Abanti, it was me." Impressed by the boy's moral courage, the teacher excused him.

December 20 marked the 90th birthday of that boy, now Bangladesh's leading Marxist theoretician and practitioner, Badruddin Umar. Teacher, scholar, editor and political activist, Umar spent his entire life pursuing his dream for a just and equitable society. It is in this quest that he shunned the comforts of a 'settled life' and undertook an arduous journey that involved studying, researching, writing, and also organising and mobilising others to participate in the struggle for transforming an unjust society. Umar reflects, "The pain, suffering, exploitation and poverty of people made me wonder, how can we explain such conditions? My studies helped me sharpen my understanding of these phenomena." "Emancipation of the poor can only take place through organised effort. That is the only route available to us that can free them," he concludes. It is this belief that worked as an anchor in Umar's life.

Dispassionate analysis of facts has been a singular trait of Umar's scholarship. In sharp contrast to the dominant discourse that blames Jinnah and the Muslim League for the partition of India, Umar argues that the Hindu Mela was the principal protagonist of the two-nation theory, a thesis that garnered the support of both Congress and Hindu Mahashabha. In a recent article titled "From Congress to BJP", he observes that the version of the two-nation theory patronised by Gandhi, Nehru and Patel was "offensive", while the one espoused by Jinnah was "defensive". He hastens to add that common Hindus did not want partition. Umar is of the opinion that if the partition of Bengal was not annulled, then it might have resulted in the development of a strong, enlightened, and stable Muslim middle class, which failed to materialise under the revised arrangement.

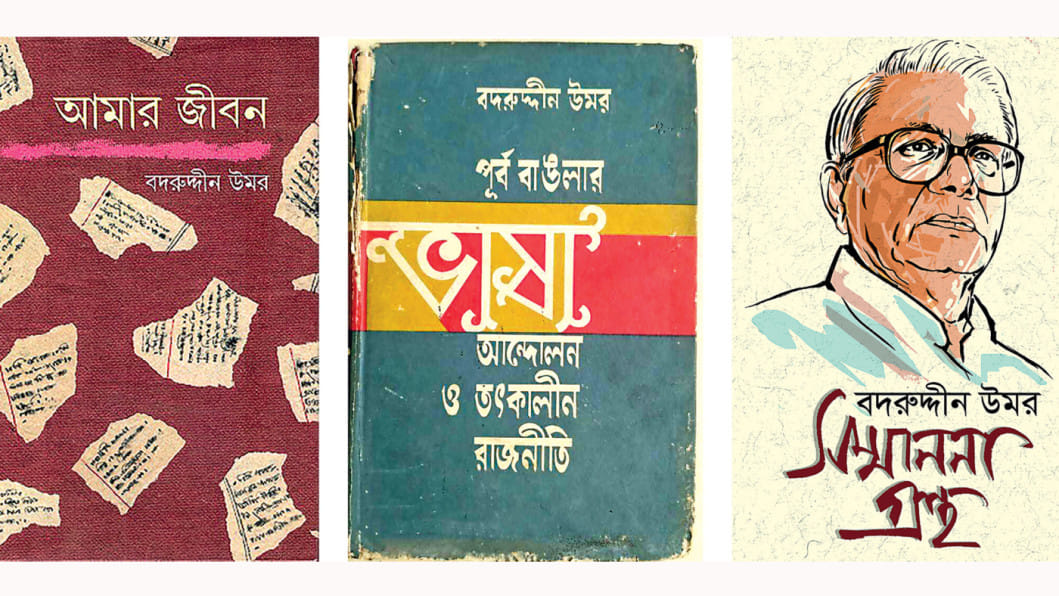

Faced with the Islamisation efforts of the Pakistani state, when Bengali Muslims were struggling with their identity, Umar's seminal trilogy Shamprodaikota (Communalism), Shongkskritir Shonkot (Crisis of Culture) and Shangskritik Shamprodaikota (Cultural Communalism) made it amply clear that the debate between being Bengali and being Muslim is a spurious one, and it was a ploy to use religion as a political tool. Umar's depth of knowledge led an analyst to suggest, "If one has to understand the socio-political grammar of Bangladesh spanning the last 150 years then reading Umar is a must" (Faruk Wasif, Prothom Alo, 20.12.2021).

No less important was Umar's perceptive three-volume analysis on the Language Movement of 1952. Against the dominant narrative in interpreting history, he built a counter-narrative with the stories and lived experiences of workers, peasants, and the common masses patiently, skilfully and cogently, establishing the class linkage between the Dhaka-based middle class and others in the periphery. As the author of 120 books, Umar's scholarship commands a wide terrain with detail, authority, and an extraordinary power of synthesis.

Despite being an avowed communist, Umar's criticism of the communist movements of both India and Bangladesh has been scathing. He felt it was an irony that instead of providing alternative leadership to the working class against bourgeois domination, the communist parties (CP) in both countries relegated themselves to the position of the "ancillary organisation of the mainstream parties". Umar terms the drawing of a parallel between the Pakistani military junta and the Awami League in 1971 by the East Pakistan CP (terming it a "fight between two dogs") as "disastrous". The inability of CP to appreciate the depth of the resistance to military rule among the people of Bangladesh led to its alienation from the latter. He found it "foolish and ignorant" that CP pursued the line of class struggle at a time when the national struggle against the genocidal Pakistani army was raging. The party's brazen dependence on an external patron was obvious, as it was designing its strategy upon the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai's call for "upholding the unity of Pakistan". Since then, Umar has been an ardent critic of both pro-Beijing and pro-Moscow variant communists, suggesting that no party in Bangladesh deserves the "communist" nomenclature.

On the crisis of socialism, Umar argues that the fundamental reason for the derailment of the Soviet variant of the socialist experiment has been the persistent aggression to bring down its government by the outside forces. He posits that Stalin had little option but to militarise, bureaucratise and securitise the system, and had to channel large amounts of resources to maintain it. While Umar concedes that the Soviet variant of socialism has failed, he insists that capitalism is also in retreat. "If anyone poses the question whether socialism has a future at all, the counter question should be asked—whether capitalism has any such future," he observes.

Umar's formidable intellectual prowess enabled him to engage in debates and polemics with his peers. During his Rajshahi University days, his influential essay on communalism drew the ire of Syed Sajjad Hossain. Umar's unabashed rebuttal of Hossain's arguments saw the beginning of his polemical writings. In an academic and political milieu that provides little scope for, let alone encourages, serious debate, Umar's refusal to uncritically accept the dominant discourse and his passion to discern the underlying reasons of a given reality earned him the reputation of a polemicist—a rarity in Bangladeshi academic and political culture. Umar doggedly maintained this trait in pursuit of his scholarship. His debate with Ashok Rudro on permanent settlement and with Amartya Sen on linkages between famine and free press are noteworthy examples.

Umar never shied away from taking a stand against repression and injustice perpetrated on any group or individual. After the Tonkin Bay incident, when the United States stepped up its war efforts in Vietnam in 1964, he singlehandedly organised the issuance of a statement from around 80 Rajshahi University teachers condemning US aggression in Vietnam and the slaughter of its civilians. This was perhaps the first protest against Vietnam War in Bangladesh. On moral grounds, he officially cancelled a three-month fellowship programme in the US.

Umar steadfastly opposed all efforts to curb the rights of national and linguistic minorities. He protested the militarisation and demographic engineering of successive governments in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the abduction of Kalpana Chakma and other activists of the Hills. Against the backdrop of a palpable silence from mainstream progressive Bengali intelligentsia on the treatment and citizenship status of the camp-dwelling Urdu-speaking community, Umar belonged to a very select group of intellectuals who extended support to their cause through his opinion pieces and by mobilising community members under the banner of Jatishotta Mukti Shangram Parishad, formed in 2011. He joined hands with Jahanara Imam in organising the People's Tribunal to exert pressure on the government for the trial of 1971 war criminals (1992).

Umar did not make any distinction between big or small cases of violation of rights. During the caretaker government of 2007-2008, when three young teachers from Rajshahi University were incarcerated for expressing solidarity with the students protesting army excesses in the Dhaka University campus, it was Umar who took to his pen and demanded their immediate release, at a time when most others were too afraid to even whisper. He was perhaps the lone person who publicly stood by Dhaka University professor Akmal Hussain when the latter was about to face mob justice for expressing his opinion at a student gathering in 2018.

Perhaps the most overlooked episode among Umar's achievements is his success in marshalling senior members of the country's intelligentsia under a common platform to combat the growing authoritarian tendencies pervading the state in the early 1970s, alongside the concomitant erosion of the fundamental rights of citizens. The 2nd amendment empowering the Parliament to enact laws concerning preventive detention (without stipulating necessary safeguards), the subsequent framing of the Special Powers Act, 1974 and its application in detaining political opponents (particularly those of the left), and the wanton abuse of authority by the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini (JRB), leading to torture, detention and extrajudicial killings, necessitated such a resistance. Under an initiative taken by Umar and poet Sekandar Abu Zafar on March 3, 1974, the Committee for Civil Liberties and Legal Aid (CCLLA) was formed at the National Press Club. Among others, Prof. Ahmed Sharif, jurist Habibur Rahman Shelley, Barrister Moudud Ahmed, editor Enayetullah Khan and writer Ahmed Sofa attended the meeting. Soon after its inception, the CCLLA began highlighting the violation of fundamental rights that are guaranteed under the Constitution, and one of its principal activities involved providing legal support to aggrieved individuals for securing the protection of the higher judiciary. In a landmark case, the CCLLA won the freedom of Aruna Sen and two of her associates—communist leaders who endured brutal torture, including rape, in JRB custody (Shangskriti, May-June 1974). In another important case of involuntary disappearance of Shahjahan (Mohsin Sharif vs. the State, 1974) supported by the CCLLA, the court found it to be a "very unsatisfactory position" that "no rules…have been framed to serve as guideline to the Bahini" and observed that "the question of life or liberty of a citizen of a country is certainly a very important question in a democratic society" and all security forces including the JRB "shall have to function according to direction of civil authority consistently with the rights of the people as secured under the Constitution and the general law…" (27 DLR 1975).

With the active engagement of the same group of associates, Umar organised the Famine Resistance Committee (FRC) in 1974, demanding gruel kitchens, cash support and jobs for the affected. The FRC held a number of public rallies in the open space that existed in front of Baitul Mukarram mosque at that time. Thus he, along with a few conscientious citizens, mounted the first effective resistance to the curtailment of rights by the State. This was the first indigenous effort for the protection of fundamental rights and the rule of law in independent Bangladesh that was bereft of any exogenous support.

Umar gave up his teaching position in Rajshahi University in 1968 to become fully engaged in politics. In his mission to defend the people's rights and dignity, he felt he should familiarise himself with their day-to-day struggles. This turned him into a strident traveller traversing every nook and corner of Bangladesh, from Sunamganj to Satkhira, from Thakurgaon to Teknaf. Until about a decade ago, he never lost an opportunity to go on organisational tours, travelling in the deck class of steamers or launches and buses, and also on tempos and vans, braving the rain and the scorching sun. In one such trip to the Batiaghata region of Khulna, I accompanied him. On one occasion, both of us were provided a sleeping space on the veranda of a thatched house of a lower caste Hindu member of Krishok Federation. When I woke up early next morning, to my astonishment, I saw this Oxford-educated Mozart-loving former university teacher deep in sleep, and sleeping next to him was the pet dog of the host family. During the same trip, while we were staying a night in a house of a snake-charmer, a snake rolled over the body of our companion, Kalu Saha. It was subsequently captured and identified as a venomous one. These incidents reveal the depth of Umar's commitment to acquaint himself with the lived experiences of the common people. These were also the conscious efforts of a person trying to de-class himself, in all likelihood a feat that no other public intellectual could ever match in this land.

Throughout his political career, Umar laid major emphasis on grooming the youth, workers, peasants and political activists by organising periodic workshops and classes. This writer recalls the five-day workshop organised in Tagore's Kuthibari at Shilaidaha, Kushtia in 1983 in which peasant, worker and youth leaders including Umar, Dr Saif-ud-Dahar, Hasan Ali Mollah, Atiar Rahman, Shah Atiul Islam, Farid Ahmed, Anu Muhammad and C R Abrar lectured for hours and fielded questions from grassroots workers from all over the country. Such occasions provided opportunities for activists of diverse backgrounds to understand the socio-economic realities that communities faced, and exchange views on how to overcome them. In that milieu of sharing of thoughts and experiences between the veterans and the youth, Tagore's Kuthibari became a hub of energy and enthusiasm for those few days. One may not be wrong to surmise that in contrast to the approach of his peers of the time, these were concerted efforts from Umar and his associates to raise the analytical faculty of the activists they took under their wings.

Badruddin Umar never cared for prizes and accolades. He is apprehensive that prizes may come with a price tag, and finds it difficult to fathom as to why writers should receive awards when they write for their own pleasure. It is out of this conviction he refused the covetous Bangla Academy Award and also the Ekushey, Adamjee, History Council and Philips awards. Likewise, holding high posts was never an attraction to him. After he joined politics, Maulana Bhashani, arguably the most prominent leader of the time, offered him the secretary's post of the National Awami Party. Not surprisingly, Umar declined.

Umar appreciates the importance of political publications to inform readers on critical issues that affect their lives. It is out of that understanding he took upon himself the onerous task of editing Ganashakti and Shangskriti (in its 47th year of publication). He also shouldered the major responsibility of publishing Naya Padadhoni during the early 1980s.

In a recent interview, Umar expressed two regrets. First, despite the massive and long-drawn struggle of the working classes, the much-desired transformation of society and polity has not occurred during his lifetime. And second, in Bangladesh, there has been virtually no recognition of his work, including the influential works on the Language Movement or on communalism. His forthright, adamant and principled stand on issues and his capacity to unmask hypocrisy, inanity and ignorance have created enough enemies even among the liberal political and intellectual elite of the land to engage in a "conspiracy of silence". Perhaps the best antidote available to them to deal with the Umar irritant is to ignore him. In contrast, in neighbouring India, intellectuals across the ideological divide, including Kazi Abdul Wadud, Maitreyi Devi, Annada Shankar Roy, Bishnu Dey, Narayon Chowdhury, Binoy Ghosh, Samar Sen and Mahashetwa Devi, have written on, commented and cited his works. Umar's work also earned him the friendship of the influential British left-wing Labour MP Tony Benn and the father of Naga nation Angami Phizo.

Ahmed Sofa considered himself lucky for having been born in "the age of Umar". This by no means is an overstatement. Umar's academic work and political activism, and no less his persona, have stirred a generation of scholars and activists, both at home and abroad. He has been a living example—an example he was as a Grade 7 student and an example he is at the age of 90, unequivocally declaring "I lived a life that I wanted to live: modest, honourable and productive." Long live my teacher Comrade Umar.

C R Abrar is an academic and a member of Nagorik, a platform for human rights and the rule of law. He was a foot soldier of CCLLA and FRC. The writer acknowledges the support of Omar Tarek Chowdhury, Barrister Jyotirmoy Barua and Shuprova Tasneem.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments