50 years of Bangladesh: The Journey towards Bangabandhu’s Sonar Bangla

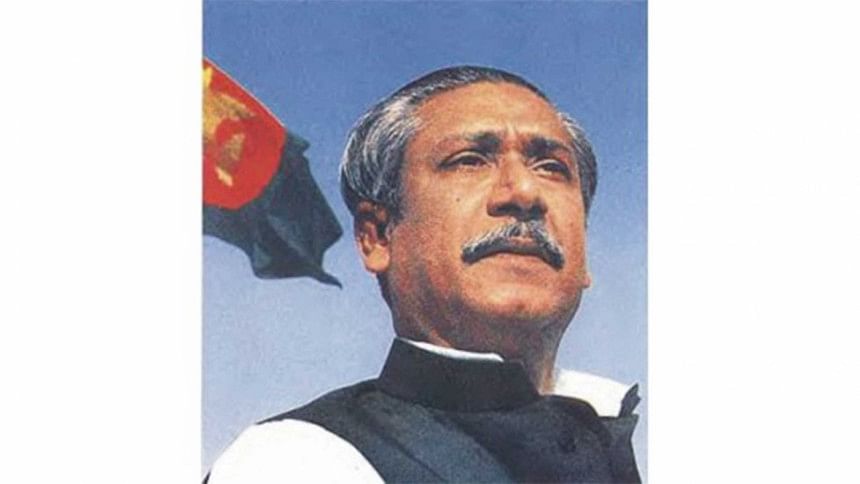

The commemoration of Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's birth centenary, and the celebrations centred around Bangladesh's 50 years as an independent nation state, will conclude at the end of the calendar year 2021. I look at this journey of Bangladesh at 50 through the lens of Bangabandhu's own vision for an independent Bangladesh, which he promised would evolve into a just society. Here, I explore how far we, as a nation and a people, have so far moved to realise Bangabandhu's promise, and what parts of his promise remain to be kept in the days ahead.

Bangabandhu epitomised his vision for Bangladesh before the people at the conclusion of his epic declaration of March 7, 1971:

Ebarer sangram, amader muktir sangram

Ebarer sangram, shadhinotar sangram

Many people have pondered on the distinction between the struggle for independence (shadhinota) and the struggle for liberation (mukti). Bangabandhu perhaps had a clearer idea in his mind about the distinction. He visualised the struggle for independence as a struggle for the establishment of a sovereign nation state—a more readily understood goal which inspired the struggle by other nation states seeking to emancipate themselves from colonial rule. But his call for liberation was a more nuanced and hence more far-reaching call. It extended the struggle beyond the realisation of independence towards the more transformative mission of liberating the people not just from the unjust bondage of Pakistani rule, but from injustices inflicted on the common people of Bangladesh for centuries as well. Years of subordination denied the people not just their democratic rights, but held them captive within an unjust social order.

Bangabandhu's commitment and struggle for self-rule was ultimately realised through the emergence of an independent Bangladesh. We survived the trauma of our bloodstained birth and moved forward over the next half century to significantly elevate its economic fortunes, experience a remarkable social transformation, and reconfigure our place in a more globalised world order. Little of this would have been possible had we not managed, in the immediate aftermath of liberation, to resurrect ourselves as a people from the ashes and debris of the Liberation War to construct a nation state, build its institutions and establish our presence in the comity of nations. That such a resurgence could be realised within three years of our national liberation, owes in no small measure to the inspirational leadership of Bangabandhu, supported by those who worked with him over long hours, with limited resources, under the most adverse circumstances, to build a nation state.

In the course of building a nation state, Bangabandhu projected his vision for realising amader muktir sangram (our struggle for liberation) through the four foundational pillars incorporated in the Bangladesh Constitution, presented to the nation within a year of liberation: Democracy, Nationalism, Secularism, and Socialism.

Bangabandhu's lifelong struggle for self-rule for Bangladesh, followed by his heroic endeavour to transform a movement for self-rule into a functioning nation state, did not go in vain. When the assassins' bullets cut Bangabandhu's life short, he could take comfort in the awareness that he had realised the most cherished part of his life's mission: the emergence of an independent Bangladesh. Furthermore, within the short span vouchsafed to him on earth, he created the structure of a fully functional nation state. But all his achievements remained a work in progress. Amader muktir sangram remained unfinished. It would, thus, be appropriate to proclaim, as his epitaph, the words of the poet Robert Frost, which so inspired President John F Kennedy:

I have promises to keep

and miles to go before I sleep

Bangabandhu's journey in this world abruptly concluded on August 15, 1975, but his dreams and hopes lived on to inspire Bangladesh's journey over the next 46 years. His unfulfilled dreams required the continuation of amader sangram, muktir sangram.

The promises fulfilled

At liberation, Bangladesh was well behind Pakistan in most areas of the macro-economy, had experienced poverty and lower levels of human development in areas such as education and healthcare. Over the course of the next 50 years, Bangladesh has moved well ahead of Pakistan in most such areas—particularly in the last 25 years, and more so in the last 10 years. Higher rates of growth have moved Bangladesh's per capita income (PCI), which was 61 percent below that of Pakistan in 1972, to exceed Pakistan's PCI by 62 percent in 2020. Such rapid rates of growth have been achieved through Bangladesh's higher rates of savings and investment, as well as its higher level of exports, which were all well behind those of Pakistan in 1972. As a result, today, Bangladesh's foreign exchange reserves are more than double those of Pakistan, while our external debt-GDP ratio is half of that of Pakistan. We are no longer an aid dependent country. Our aid-GDP ratio is now around two percent, whereas Pakistan has required periodic bailouts from the international community. Bangladesh's infrastructure development, which lagged far behind that of Pakistan in 1972, has also moved ahead in such areas as power generation, where our capacity, which rapidly expanded in the last 10 years, is nearly double the capacity of Pakistan.

In the area of human development, Bangladesh's human development indicators (HDI) were below those of Pakistan in 1990, but are now well ahead. Bangladesh has managed to lower its population growth rate compared to Pakistan, so that today our population levels are lower than that of Pakistan, whereas in 1969-70 we accounted for 53 percent of the undivided Pakistan's population. At the same time, due to better health provisioning, Bangladesh's life expectancy, which was well below Pakistan in 1972, is now five years above that of Pakistan. Similarly, in the area of education, in such indicators as years of schooling and literacy rate, we once lagged behind Pakistan, but have now moved ahead. As a result, Bangladesh's levels of multi-dimensional poverty, which was once higher than that of Pakistan, is now well below it. Perhaps the most dramatic advances have been registered by the women of Bangladesh, whose gender development index has not only moved well ahead of Pakistan, but is ahead of India as well.

All these indicators of Bangladesh's progress, compared to Pakistan, have served to validate Bangabandhu's vision that an independent Bangladesh, in full command of its own destiny, would be able to move ahead more rapidly than under the dominance of Pakistan. In the course of these 50 years, Bangladesh's progress may have exceeded Bangabandhu's expectations.

Bangladesh's progress is not merely measurable in statistical terms, but is manifested in the major structural changes in the economy and the social transformation which have taken place as a result of our liberation. Bangladesh has transformed itself from a largely agrarian society, exclusively dependent on growing paddy for subsistence and jute as a cash crop, where agriculture was the principal source of both GDP and household income. We were once industrially backward, dependent on a single industry—jute—and a single source of exports—jute products. Today, the GDP contribution of industry exceeds that of agriculture, and even in the rural areas, more than 50 percent of household income derives from non-farm sources. Our exports, now largely dependent on the manufactures of RMG, rather than jute products, have grown exponentially, while remittance from our migrants overseas have emerged as our largest foreign exchange earner, which has strengthened our balance of payments.

These remarkable changes in our economy have been driven by the emergence of a dynamic entrepreneurial class, which is represented not just by the RMG entrepreneurs and corporate business houses, but extends across a much broader social spectrum. This, inter alia, includes medium, small and micro-entrepreneurs, women from poor rural families who have participated in the microfinance revolution or have travelled to the urban areas to contribute their services to fuel the rapid growth of the RMG sector, the NGOs who have promoted more inclusive growth, the migrants who have taken great risks to travel across the world in service of their families, and a new generation of IT entrepreneurs.

The promises still unrealised

While Bangabandhu's expectations from shadhinota may have been realised, his expectations from amader muktir sangram, which would take us towards his vision of a just society, remain part of the promises that we, as a nation, need to honour in his memory. While Bangladesh's economy has registered impressive growth, and poverty has been reduced, income inequalities and social disparities have widened. This represents an unjust distribution of the gains from our development and an inadequate recognition, in terms of policies and public support, of the larger constituency of social forces which have also driven our progress.

It is suggested that this widening of social disparities owes not just to policy and allocative deficiencies, but to an unjust governance in various spheres, where laws already enacted are not decisively acted upon, policies are not fully implemented, and regulations are weakly enforced. Such deficiencies in governance originate both in the incapacity of the government to discharge its commitments and in the emerging political economy where an increasingly powerful business elite, patronised by the state, is empowered to influence policies and public action. Such tendencies are manifested in the growth and perpetuation of the default culture—the weakness in enforcing government regulations related to areas such as road safety, building codes and environmental protection, and also the inability to ensure that the conflict of interest rules are applied so as to make sure that competitive forces operate in all public procurement and development projects. In consequence, public policies, in the way of fiscal policies and subsidies, along with public expenditure priorities, tend to favour the business elite at the expense of less privileged social groups.

Economic and social injustice, originating in state actions, are compounded by the depreciation in the quality of our democracy, manifested in the weakening credibility of our electoral process, erosion of the freedom of media, unfair access to public services, and inequitable protection under the rule of law as well as from law enforcement.

The capture of our electoral institutions by the business elite, and the dominance of money and force in our electoral contestation have further moved us away from Bangabandhu's vision of a just democratic order, where the voices of the less privileged members of society could be clearly heard in our institutions of governance.

In conclusion, I suggest that much can be done towards bringing greater justice to the governance process if the ruling regime remains committed to realising Bangabandhu's vision of a just society. Ensuring the rule of law for all, implementing policies and enforcing regulations remain within the domain of a well-intentioned government, and do not require revolutionary upheavals.

The move to realise more substantive advances towards a just society may need structural changes, which require new legislation—even constitutional amendments—supported by changes in the balance of power that accommodates the needs, rewards the contributions, and gives voice to the less privileged segments of society. Here, too, the reforms suggested in my presentation of broadening access to the ownership of assets, ensuring more equitable participation of the less privileged in the marketplace, delivering quality education and healthcare to the less privileged, and continuing Bangabandhu's struggle for the greater democratisation of both the institutions of democracy and the institutions of governance, can remain achievable goals. But such moves in the days ahead towards a more justly governed society, underwritten by policies for structural change, demand a total commitment from both state and society to carry on and sustain the struggle to realise the historic vision of Bangabandhu.

Prof Rehman Sobhan is the chairman of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). This article is a summary of his lecture on Bangabandhu's birth centenary, titled "Bangabandhu's Vision for a Just Society: Promises Kept and Promises to Keep," delivered on December 6, 2021, at the inaugural session of "50 Years of Bangladesh: Retrospect and Prospect," a four-day conference organised by CPD in collaboration with Cornell University, US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments