An apology long overdue

On a symbolic visit to Kigali, Rwanda this year, French President Emmanuel Macron recognised France's extensive role in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, asking for the "gift of forgiveness" from those who survived the atrocities—without, however, putting forth an official apology. Though this has disappointed many, Rwandan President Paul Kagame praised Macron, saying, "His words were something more valuable than an apology. They were the truth."

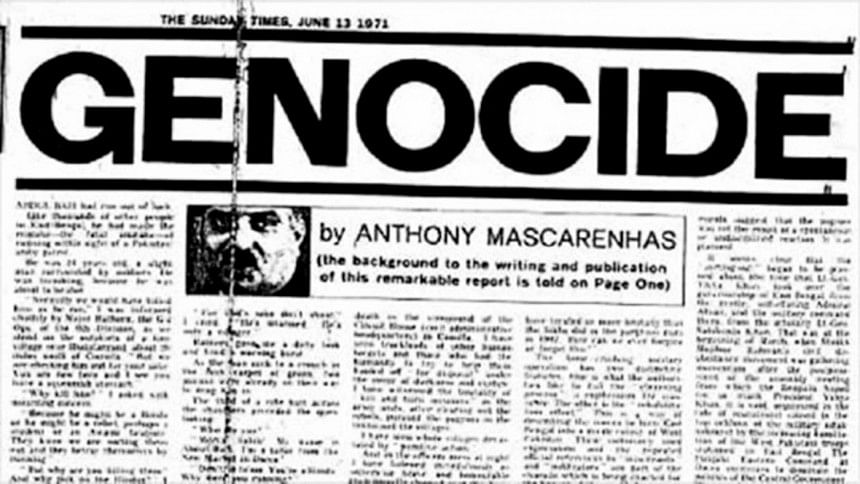

Bangladesh, currently celebrating its golden jubilee of independence, has achieved remarkable feats in economic and social indicators, rising from a looted and ravaged state to gradually becoming a country poised to become the 28th largest global economy by 2030. On the other end of this glorious timeline, though, lies a dark, painful episode steeped in atrocities, which ended with the surrender of West Pakistan—but with no official apology. Fifty years have passed, and it appears we have risen quite remarkably from the ashes, but does this long duration and success on our end waive the need for an apology or simply, as the Rwandan president put it, the acknowledgement of the "truth"? And that, too, a truth that formed the basis of the birth of these two nations in question? While the flags are proudly hoisted and songs sung on December 16, commemorating independence in Bangladesh, the same day is uncomfortably recalled in Pakistan, somewhat distastefully for us and conveniently for them, as the "Fall of Dhaka" or the "Dismemberment of Pakistan."

Time and again, Bangladesh has pressed Pakistan for an official apology for the 1971 genocide of Bangladeshis, and each time, the demand has been met with elusiveness—perhaps under the guise of partial amnesia of the crimes that had been committed—or just the ruthless political logic that wartime military actions do not warrant an apology. Not to be confused with casually-thrown, superficial diplomatic regrets—like the one President General Pervez Musharraf expressed during his visit to Dhaka in 2002—a national apology is a genuine condemnation of a grave historic wrong, and a collective commitment to establish justice and truth, made usually by the head of state. It upholds changed values of the malefactor and facilitates reconciliation with the ones violated. Interestingly, the apology not only attempts to rectify wrongdoings of the past, but it reverberates into the present and future grand narrative(s). However, this also begs the question whether such an apology risks the chances of evoking ripples of wartime guilt across future generations, or if it allows the country to move forward restoring national dignity.

Germany would perhaps be the ideal advocate to argue in favour of the latter. The 1970 historic moment of then Chancellor Willy Brandt kneeling in silence at a memorial to Warsaw Ghetto became the image of atonement for the contrite nation. Explaining his gesture, he had commented, "…I did what we humans do when words fail us." Starting from the Nuremberg trials and unequivocal apologies, to educational reforms focusing on denazification—their whole mechanism of apologising did not just focus on redressing the horror of the past, but also on enlightening the future generations. To prevent the repetition of such a horrendous crime, no stone was left unturned to ensure that the next generations had no confusion about the culpability of Germany.

If we juxtapose this against the government-endorsed textbooks that are still prevalent in Pakistan's schools, it is apparent that the authorities, even today, are trying to spoon-feed their youth nonsensical "conspiracy theories" about the 1971 war, while washing their own hands of any liability for the massacre. These theories—propagandising state-level scheming by India and Russia and the US—are factually taught in their history classes, which, in turn, discounts the blood-soaked sacrifice of an estimated three million people. The nine-month-long democratic struggle of Bangladeshis and their terrifying memories of the genocidal military operation are appropriated and hijacked time and again, to make us appear as a by-product of the Indo-Pak conflict.

Going beyond a classroom lesson, the Army Museum in Lahore, inaugurated in 2016, proudly exhibits a plaque that declares, …"(The) Indian government resorted to state sponsoring of terrorism inside East Pakistan through the creation of various terrorist organisations like Mukti Bahini…", flagrantly labelling our national heroes as terrorists. Denial then took the shape of a cancelled conference this year. Organised by two Pakistani institutions, the conference aimed to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Bangladesh Liberation War by highlighting new analytical literature and research to better comprehend the conflict of 1971.

It seems like their deep-rooted institutionalised tendency to obliterate history and resort to selective national remembering are still in practice at the state level. A distorted narrative of our Liberation War has already been established in Pakistan's mainstream national discourse, with the report of the Hamoodur Rahman Commission (HRC)—a post-war inquiry commission sanctioned by the Pakistan government then—kept hidden from the public for decades. Every copy of the report was ordered to be burnt by then President Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, allowing the guilty, which included many military bigwigs of Pakistan, to escape blame for so long.

On the other side of the coin, there are strong opinions and theories circling around political apology. Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard, when asked to offer an apology for the mistreatment towards the Aboriginal peoples, asserted that today's generation is not liable for the wrongs committed by their predecessors. A few studies factoring in variables such as time and generational gap, in between the crime committed and the apology offered, suggest that this "…temporal break should theoretically weaken the need for an apology," affirming Howard's claim.

Despite the notion that guilt is not passed on, there is no turning away from the fact that history shapes our present identity and, therefore, it is in the present that responsibility for past actions must be borne. According to a study report titled "Why do countries apologise?" conducted at the University of Texas at Austin, "Values such as human rights and justice are atemporal and, thus, violations of them in the past persist throughout and shape the present. As a result, apologies remain relevant and necessary despite the passage of time." More so, heads of state are custodians and keepers of national values and official memories, rendering them responsible for ensuring historical accuracy in their official public memory and paving the way for reconciliation.

This brings us to the recent chain of events indicating reconciliation attempts from both Bangladesh and Pakistan. Ministerial and diplomatic-level meetings have hinted at enhancing diplomatic and economic ties between the two countries, with Pakistan's eyes ambitiously set on wider regional connectivity and economic activity. Prime Minister Imran Khan made their resolution even more concrete by congratulating Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on the 50th Independence Day of Bangladesh—a move commended by many. However, for any meaningful bilateral development to occur, Pakistan must extend an unconditional official apology for the heinous atrocities of 1971—a stance that has been reiterated by Bangladesh.

An apology is the ultimate prerequisite to making public amendments, initiating a social repair, and re-establishing trust, which means Pakistan's idea of emphasising economic revival while neglecting and downplaying wartime accountability will prove to be ignorant and futile. In order for these two nations to begin a new chapter on a clean slate, coming to terms with their collective past is critical. The Bangladeshi survivors of the 1971 Liberation War and their family members live a life of loss and transgenerational trauma, and that has only been compounded by Pakistan's failure to give recognition to past injustices and simply ask for forgiveness. While this acknowledgement and apology will not undo the horrors, they can renew the scope for proper awareness for the next generations, break ground for genuine reconciliation and, perhaps, bring some degree of relief for the ones who are still tormented by the vivid memories of roaring bullets.

Iqra L Qamari is a junior consultant at the Public Private Partnership Authority.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments