Are the new online laws designed for the 2023 polls?

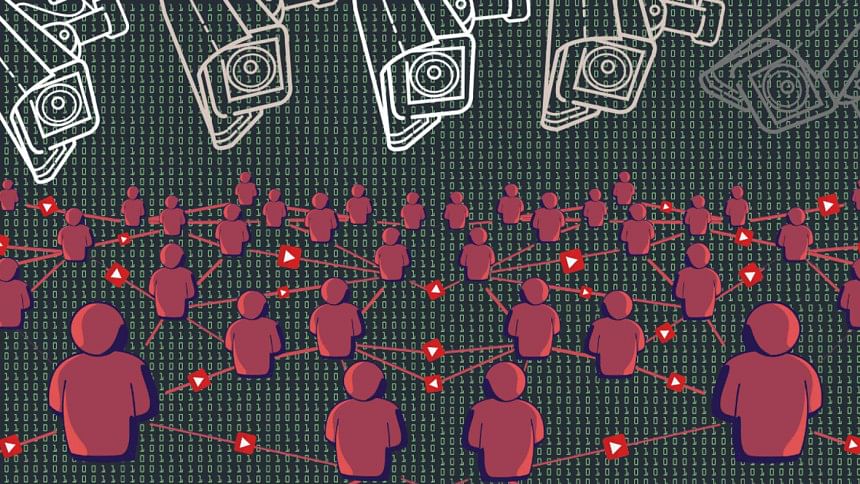

The recent publication of the drafts of two long-awaited legislations on regulating the usage of internet in Bangladesh have stoked some debate on their likely impact on both the citizens and businesses. However, not much has been said about the government's motivation and objectives behind the sudden rush in legislating these laws, which should have been enacted years ago. Both of these draft laws—the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms, 2021, and the Personal Data Protection Act, 2022—have a common principle, which is to allow the government ever more control on everything we do over the internet. Hence, the draft OTT regulations have more provisions to allow state surveillance over contents on the grounds of state security, instead of giving freedom to the citizens to enjoy cyberspace without fear. Similarly, instead of affording greater protection to an individual's privacy rights, many of the proposals under the draft data protection law would actually increase the government's access to personal data, thereby increasing their surveillance capabilities.

The question of data protection for the state and its citizens is not necessarily the same, especially in countries that are autocratic or hybrid democracies. The right to privacy, however, is enshrined in the constitution as a fundamental right in most countries in line with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but in autocracies and weaker democracies, the state itself poses the greater threat to individuals' privacy. Rights groups allege that in Bangladesh, too, the government poses the greatest threat to citizens' privacy.

According to Freedom on The Net 2021 report published by Freedom House, internet freedom in Bangladesh has reached an all-time low. The reasons cited include the applications of the Digital Security Act (DSA) and "new evidence of the extent of government surveillance capabilities" that came to light. The report alleges that the online sphere continues to be impacted by government-hired civilian contractors who hack accounts and use false copyright infringement complaints to get content removed. Besides, it noted that partial restrictions of internet and communication services during protests, elections, and tense political moments have become common. Strategic advisory firm BGA Asia, speculating the new data protection law coming into force before the next elections, says, "Optimists may point to other countries around the world that have passed laws to protect their citizens' personal information and ensure data privacy. However, many of the thought leaders in Bangladesh think otherwise."

The reasons or objectives for the proposed data protection law noted in the draft clearly shows that the government's priority and emphasis are anything but protecting personal privacy, as it has been demoted to the third and fourth positions on the list. Though it has been suggested that the European data protection law, the EU GDPR, has been used as a model to draw up our own legislation, the objectives could not have been more stark. Number one objective of the GDPR says, "This regulation lays down rules relating to the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and rules relating to the free movement of personal data." And the second objective reads, "This regulation protects fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons and in particular their right to the protection of personal data."

The other proposed legislation, the BTRC Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms, 2021, also attaches higher importance in the name of sovereign control on curbing the freedom of users. US-based advocacy organisation the Internet Society, using their Internet Impact Assessment Toolkit, concludes that the proposed law will be "making the internet less open to those that want to utilise it." Apart from introducing significant compliance costs to service producers, it says the law's "vaguely defined scope for objectionable content risks depriving internet users in Bangladesh of useful and educational information." The Internet Society says the regulation enables a lot of unaccountable actors and actions, both from government enforcers and complying intermediaries. It argues that along with the resulting lack of privacy in online communications, it will create an uncertain, unpredictable, and non-transparent environment for businesses to operate in, thereby making the internet and online services in Bangladesh less trustworthy, and less appealing for the citizens to use.

In both the legislations, regulators, the planned Digital Security Agency and the current BTRC do not have any independence whatsoever, and rather will be something similar to a government department. These draft rules have also given almost blanket indemnity to all government agencies that would certainly make these regulatory bodies powerless, which is quite opposite to the roles played by regulators in Europe and many other advanced countries.

Two cases can be cited here that exemplify the degree of protection citizens should receive and the independence the regulator should have. In January this year, the European Union's data protection watchdog, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), forced the EU's police agency, Europol, to delete much of a vast store of personal data that it has been found to have amassed unlawfully. Those sensitive data had been drawn from crime reports, hacked from encrypted phone services, and sampled from asylum seekers never involved in any crime. In the UK, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) fined the Cabinet Office 250,000 pounds in 2020 for the leak of personal data from the New Year's Honours list.

In contrast, we have seen all sorts of data breaches, including biometric ones, in Bangladesh, which presumably would not have been possible without direct or indirect roles of government agencies. No one has been held accountable for such breaches. But people have been persecuted based on suspicion and spurious claims. In this context, it could be argued that the sudden rush for these regulatory legislations had been warranted due to the upcoming political developments, including the country's next general election due to be held by December 2023. Concerns about the likely use of both the data protection law and the OTT regulation by the government to exercise greater control over citizens' online activities during electioneering may not be entirely misplaced. Here's a reminder that the DSA enactment happened just two months before the parliamentary election in 2018.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist and writes from London, UK. His Twitter handle is @ahmedka1

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments