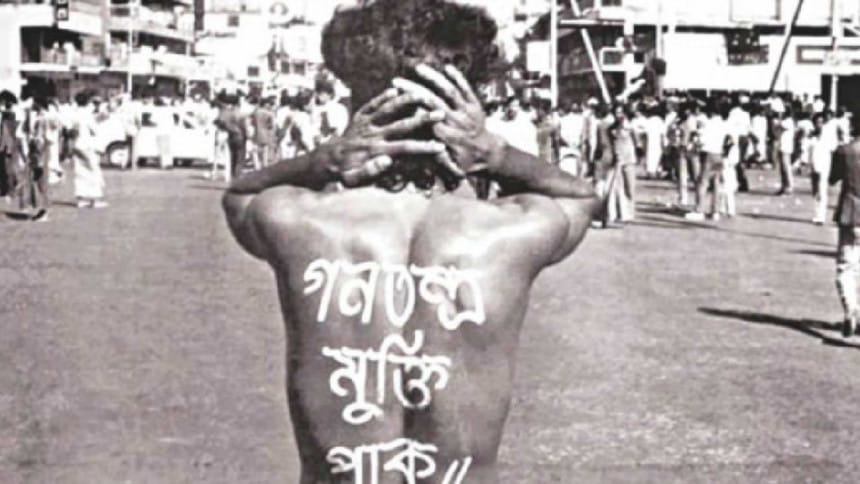

Democracy Day: A revolution betrayed

During the rule of HM Ershad (from March 24, 1982 till December 6, 1990), the phrase "Ershad Vacation" used to be widely used. Ershad was in power as the chief martial law administrator and the president of Bangladesh for nearly nine years. During his regime, rather than politically tackling the unified student movements, he would frequently pursue the policy of repression and the strategy to shut down educational institutions, whenever needed.

Ershad never had to take part in due political process, nor did he have to be elected. What Lt Gen Ershad did was participate in political activities while he remained the chief of army staff. On December 2, 1983, a political party was formed in his support—the "Janadal"—headed by Justice Ahsanuddin, whom Ershad had appointed as the president of Bangladesh. A few days later, on December 10, Ershad declared himself as the president by exercising his authority as the chief martial law administrator. On January 1, 1986, instead of Janadal, he formed another political party named the "Jatiya Party," with former Awami League leader Mizanur Rahman Chowdhury as its convener. A few days later, Ershad himself took charge as the party chief, and in the party constitution, he was given absolute control. Military ruler Ziaur Rahman had followed the same tactic to ascend to power and engage in the political process. Both Zia and Ershad had the same political mentor: Pakistan's military ruler Field Marshal Ayub Khan.

Ershad's rule was unique in some ways. Besides imposing martial law, he repeatedly declared a state of emergency and reinstated martial law. He snatched away freedom of the press and frequently used the army to suppress political movements. Both Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia emerged as popular political leaders at that time, staying active on the streets during the movement to oust Ershad. Both of them established their authorities at all levels of their respective parties during that movement. They led two different political alliances and were also distinct in their views and ways. But during the movement against Ershad, they sat together at least three times to discuss the political situation. They held political programmes simultaneously to end HM Ershad's rule for years. Together, they called nationwide strikes at least 72 times. Besides, the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League and the Khaleda Zia-led BNP were involved in around 250 more strikes that were called at local levels. Ershad would frequently place the two leaders in "security custody" (in their respective homes). But they were indomitable.

In November 1983, the Awami League and the BNP, through their respective alliances, put forward a five-point demand, which included a parliamentary election under a non-partisan government. By then, the Awami League had decided to return to the parliamentary system of government, instead of the presidential system. BNP, however, preferred the presidential system, even though they had condemned the Baksal rule.

The "Manifesto of the Three Alliances"–one alliance led by the Awami League, one by the BNP, and the third one by the five leftist parties–which was unveiled on November 19, 1990, presented the formula to make Ershad step down. It said Ershad would have to hand over power to a person nominated by the three alliances. Three weeks later, he had to relinquish power to Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed, who was nominated by the three alliances.

Shahabuddin served as the president of the caretaker government which oversaw the fifth parliamentary election held on February 27, 1991. The advisers to the caretaker government, appointed by the chief justice, were nominated evenly by both the Awami League and BNP. Although BNP won more seats than the Awami League in the election, it had to make an alliance with Jamaat-e-Islami to get an absolute majority to form the government. During the 1971 Liberation War, Jamaat-e-Islami not only aided the genocide, rape and looting committed by the Pakistani aggressors, but also took part in the crimes. The party and its student front, Islami Chhatra Shangha, formed the infamous al-Badr and Razakar bahinis who, through their violent activities, proved to be worthy allies of Yahya-Tikka-Niazi's barbaric forces.

The BNP-Jamaat collusion is considered a grave mistake in our politics. Many well-wishers of the BNP and party insiders believe that the party is still paying the price for this misstep.

After coming to power in 1991, the BNP, with the help of Awami League, returned to the parliamentary system of government. But the fifth parliament could not become the "centre of all political activities" as specified in the manifesto of the three alliances. The Awami League lawmakers boycotted parliament sessions several times in a row. On December 28, 1994, 147 members of the Awami League, Jatiya Party, Jamaat-e-Islami and NDP resigned simultaneously, demanding the sixth parliamentary election to be held under a caretaker government.

The manifesto was undoubtedly a record of important political understanding. It contained pledges such as repealing the Special Powers Act, 1974, giving autonomy to Bangladesh Betar and Bangladesh Television, and separating the judiciary from the executive branch in order to establish the rule of law. The three alliances had also pledged to allow the local government bodies to operate in a strong and independent manner.

But clearly, the pledges were not met. Although both the Awami League and the BNP had agreed not to take in any of the "associates of the dictator Ershad," they did not keep their word. Questions were raised against many—who later joined these two parties and got nominations to participate in the national as well as local body elections—about their loyalty towards democracy, freedom of speech, human rights as well as the ideals and values of the Liberation War.

The pledges that the three political alliances had made in their manifesto were essential for our smooth transition to democracy. The Awami League and the BNP leadership played key roles in formulating that manifesto. The student organisations then also supported that manifesto. Why couldn't they continue that political consensus in later years? There is a common term in English that goes, "A revolution betrayed." Why the manifesto of the three alliances could not be implemented in Bangladesh should be looked into and analysed.

Ajoy Dasgupta is a freedom fighter and Ekushey Padak-winning journalist. This article was translated from Bangla by Naznin Tithi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments