How long will patriarchal mindsets impede gender justice?

A couple of weeks ago, I spent the night in a district town's Parjatan hotel. The area was not too isolated, but these hotels tend to be on quite large grounds, and it felt secluded and somewhat eerie. The rooms all faced an overgrown garden, and I remember thinking to myself: if I believed in ghosts, this would be the place where I encountered one.

After dinner, I walked up the stairs and down the dimly lit corridor that led to my room. As I was about to unlock the door, I heard two voices—definitely male—coming up very close behind me. I didn't really even think about it. I froze. Once they passed me by, I quickly unlocked the door, went inside, and bolted it. It was only after I went indoors that I realised my heart was racing, and I had been holding my breath.

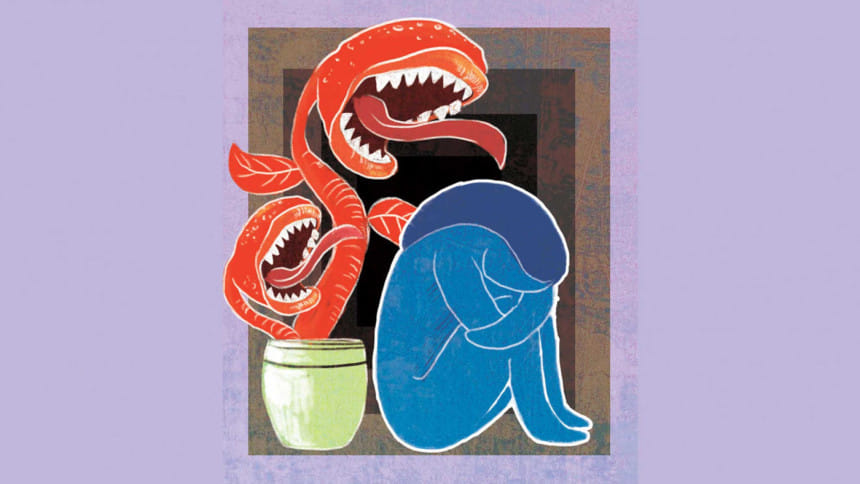

I narrate this story because I think many women would be able to relate—whether it is in dark corridors, unfamiliar streets, public transport or empty classrooms. Most of us are far more afraid of men than of any other threats, real or imaginary, when we are alone.

Not all men, of course, as many would point out. But as many more would say, we really don't know which ones. And without a shred of doubt, I can tell you that all women have internalised this defence mechanism that raises red flags and has you expecting the worst, even in the most ordinary/commonplace situations.

However, while the extreme violence faced by women and children is ample reason for us to be fearful—according to Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK), 1,178 women were raped in Bangladesh in the past 10 months, of which at least 220 were gang rapes—this tends to translate mainly into a fear of "stranger danger." Despite all reports and research pointing towards a greater likelihood of being abused by someone in a position of trust, we cling to the idea that the threat of sexual violence is most likely to come from a nameless, faceless stranger—an "animal" who deserves the worst form of punishment, rather than a neighbour, teacher, friend or family member, including and especially an intimate partner.

The fact that children are particularly at risk of sexual violence points towards how exposed the most vulnerable are to being abused by a trusted individual. Although specific data could not be gathered for around 30 percent of the 1,178 rape cases recorded by ASK, they still found that 129 were teenagers (13-18 years old), 110 were 7-12 years old, and at least 74 of this year's rape victims were under six years old.

Last week, there were two such reports of child rape. On November 22, a madrasa teacher named Abdul Malek was arrested for raping a nine-year-old student; she had gone to him to learn Arabic, and after class, he asked her to stay back and raped the child. The day before that, another man named Nazmul Haque was arrested for raping and killing a six-year-old who lived next door to him; her body was discovered in a sack under his bed. Did these children's parents ever imagine that they would suffer such cruelty at the hands of an educator and a neighbour?

The problem with an over-representation of stranger danger is not just that we tend to rule out the danger posed by people in positions of trust—it almost always comes with the patriarchal implication that, since public spaces are so unsafe, women are "better off at home." This fear is possibly one of the primary reasons behind the shockingly high levels of child marriage in Bangladesh. Although poverty is definitely a driver, there is also the idea that once a girl reaches "womanhood," it is better to get her married, rather than risk her chastity at the hands of a strange man—i.e. a man she is not married to.

Which brings us to the topic of intimate partner violence and marital rape. ASK's report also revealed that, in the last 10 months, 197 women have been killed by their husbands, and 128 women committed suicide after facing domestic violence. In the 2015 Report on Violence Against Women survey conducted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (its most recent one), it was found that 25.2 percent of Bangladeshi women experienced sexual violence at the hands of their partners.

In this regard, two especially horrific images are seared into my mind. The first is of 14-year-old Nurnahar, decked in full bridal wear and weighed down by gold, standing next to her husband (read: abuser) 35-year-old migrant worker Rajib Khan—a look on her face that can only be described as terror. She started bleeding on September 20 last year, the first night of her marriage. By October 25, she was gone. The cause of death was excessive genital bleeding.

Nurnahar's abuser went scot-free, because not only does Bangladeshi law not criminalise marital rape (even if the parties are separated), it permits the marital rape of children over the age of 13. According to an Equality Now report, there is a mismatched punishment clause which only provides for punishment of two years' imprisonment in cases of marital rape of a child under 12 years of age, with no punishment designated for marital rape of children over the age of 12.

The second image is the plump, smiling face of Suraiya Newaz Labonno—a seemingly happy 17-year-old with yellow ribbons in her hair, shared by The Daily Star only last month. About a year ago, she was forced into marriage and almost immediately became pregnant. On October 9, 2021, Labonno poured kerosene over her body and set herself on fire. Five days later, she delivered her child—stillborn—before succumbing to her wounds. Her family alleges that she was consistently abused because of dowry demands, but we will never know what truly happened for this teenager to be so devoid of hope to take the steps that she did.

Both of these children were abused by an intimate partner, yet they were not able to reach out to anyone for help—not the local authorities, not any law enforcement agency, no friends, no teachers, and definitely not their families. And they were only children. When an adult woman tries to tell people that her husband has been forcing himself on her, day in and day out, without her consent, and that this constitutes as sexual violence, she is likely to be met with nothing but ridicule and scorn.

And this, perhaps, leads to the heart of the issue of gender-based violence in Bangladesh: the fact that, regardless of the laws that protect them, women are still simply viewed as objects deserving of masculine protection or subjects of terrible violation, and the responsibility of preventing the latter rests on the guardians who have "ownership" over a woman, and thus has sanction to police her behaviour.

As the crass and insensitive comments of Judge Kamrunnahar, who presided over the Raintree rape trial, demonstrates, this does not just affect society's treatment of women—it impacts how they are viewed by the state and the institutions that are meant to protect them. The judge did not only suggest the 72-hour time limit for rape victims to come forward—an idea that was later trashed by experts, including the law minister. According to media reports, she argued that the victims "were partner to the sexual intercourse wilfully because they willingly went to the party, danced, drank alcohol and they swam in the pool."

The fact that a member of the judiciary could trivialise the trauma of a rape survivor in this way is really quite incredible, but sadly, not surprising. Such toxic, patriarchal mindsets from people in positions of power (both men and women) are one of the biggest stumbling blocks to gender justice in our country. As academic Paulomi Chakraborty puts it: "The state… duplicates the violence of fixing the value of a woman in terms of her sexuality," treating her "merely as currency in an honour economy."

As long as these mindsets don't change, we will always be looking over our shoulders, because we cannot put our faith in a system that sees us as nothing more than vessels of chastity and morality. As the firebrand Indian feminist Kamla Bhasin once famously said: "Why did you place your community's honour in a woman's vagina?" And how much longer will we continue to suffer the indignity of being dehumanised in this way?

Shuprova Tasneem is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Her Twitter handle is @ShuprovaTasneem

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments