How Moscow helped Washington win a strategic battle against China

It was nothing short of a daring James Bond mission.

On January 28, 1998, Xu Zengping, a Hong Kong-based tycoon, was standing on the deck of a 300-metre vessel in Mykolaiv, Ukraine. "We must have it for our navy," he thought, awed by the steel leviathan's size and strength. The half-built vessel was lying abandoned at Mykolaiv shipyard in southern Ukraine near the Black Sea coast.

The former Soviet Union's strategy was to spread its defence industry across the vast country to reduce its vulnerability to military strikes. Ukraine was the repository of many sophisticated naval and aviation technologies, including three major shipyards and several related research facilities. Mykolaiv shipyard began construction of the Kuznetsov-class carrier, the Varyag, in 1985 for the Soviet Navy. But the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 when the work was only about two-thirds complete. The construction work stopped as there was no money and no buyer. The cash-strapped shipyard badly needed a buyer and found one in Chinese businessman Xu. But he was also a former Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) officer, which no one in Ukraine knew.

The PLA had long been receiving Soviet defence equipment in its modernising drive. Moscow often charged a hefty price for its technology, suspected Beijing's intentions, and sometimes provided more advanced technology to other countries, such as Vietnam. All that changed after the fall of the Soviet Union, as much of the defence technology remained in the now independent states such as Ukraine. The Varyag offered the opportunity to fulfil the PLA's long-cherished goal of having an aircraft carrier. It assigned Xu a top-secret mission: bring the Varyag to China under the cover of a floating casino-building plan.

After several months of nudging, stacks of US dollars, and many alcohol-drenched parties, Xu sealed the deal for a basement-bargain price of USD 20 million in an open auction in March 1998, outbidding opponents from the US, Australia, South Korea and Japan. Still not sure if he could get hold of the vessel, the next day Xu had 40 tonnes of its design documents loaded onto eight trucks to drive overland to China. After making the last payment on April 30, 1999, Xu floated it to China's Dalian Port. That the vessel also had four brand new engines, each costing USD 20 million, was a complete secret. On paper, it was only a hull. The PLA commissioned it in 2002 as its first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning.

Naval technology was not the PLA's only target. Ukraine was also a convenient hunting ground for aviation technology, especially advanced engines for fighter jets and helicopters. It has the capability and expertise to build advanced weapon systems, such as radar, electronic warfare, aerodynamic weapons, and air defence network. The most notable case of PLA benefitting from Ukraine's aviation technology is the J-20 fighter jet, first built by Chengdu Aircraft Plant No 132 in January 2011. J-20 design was developed by reverse-engineering Russia's Sukhoi Su-27SK fighters that Moscow agreed to sell to Beijing in the 1990s. Such a stealthy development was possible by close cooperation from Ukrainian experts, many of whom had long been working for the PLA.

Beijing also planned to take over the high-profile Ukrainian aviation enterprise, Motor Sich, the only entity from the Soviet era still capable of producing an entire jet engine on its own. Sometime before 2017, Beijing-based aviation firm Skyrizon secretly paid its offshore owners USD 700 million to gain controlling shares in Motor Sich.

That alarmed Washington, not least because it also wanted to acquire the same entity through Erik Prince, a high-flyer private security contractor infamous for the 2003 Baghdad massacre by his company Blackwater. Beijing's increased technological strength had already been a concern for Washington, as stated in its National Defence Strategy of 2018. President Zelenskyy assumed office in May 2019. In August, President Trump's National Security Adviser John Bolton met him to block the deal with Skyrizon that would be disadvantageous for the US in its strategic rivalry with China. In January 2021, Zelenskyy declared sanctions on Skyrizon and its parent company, Beijing Xinwei Technology Group, practically killing the deal.

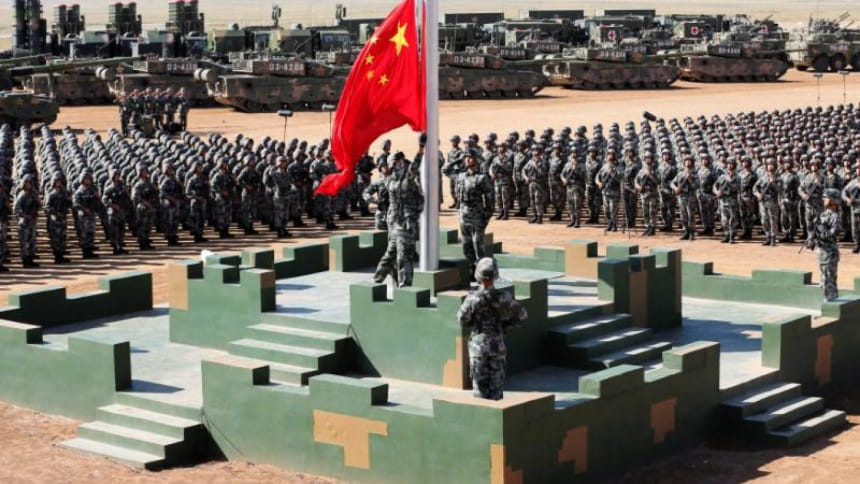

The aircraft carrier mission and the attempted Motor Sich acquisition illustrate how much importance the PLA attaches to gaining Ukraine's defence technology. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) records show that Ukraine's largest arms buyer is China (about 60 percent). Ukraine is China's third largest supplier, Russia and France being the first and the second, respectively, showing its products' high quality and sophistication. It offered everything China needed to bolster its military capabilities. But the Russian invasion has changed all that.

The shipyards, Motor Sich plant, and many other industrial establishments that could offer defence technology are now destroyed by Russian missiles. That has made a significant dent in Beijing's defence plans. With these and most of Ukraine's industrial capacity gone, Washington has certainly secured a strategic gain against Beijing while Moscow and Kyiv are paying the price.

But the hugely destructive path Washington has adopted to achieve it shows its desperation typical of a declining power, just as Russia's invasion exposes The Kremlin's desperation. Ukraine is in ruins. Its economy faces a bleak future and will take decades to rebuild, if at all, not to mention the catastrophe this brutal geostrategic game has inflicted on human lives. But rising powers can patiently wait for another opportunity. Time is on their side.

Dr Sayeed Ahmed is a consulting engineer and the CEO of Bayside Analytix, a technology-focused strategy and management consulting organisation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments