Learning to Love Dhaka

The other day, a Dutch friend of mine and I were having lunch when I mentioned how chaotic I'd heard the Dhaka airport was now. "Frankly," she said, "I never notice the airport. I'm always so sad to be leaving the country." We continued chatting over our lunch, but my mind lingered on what she'd said.

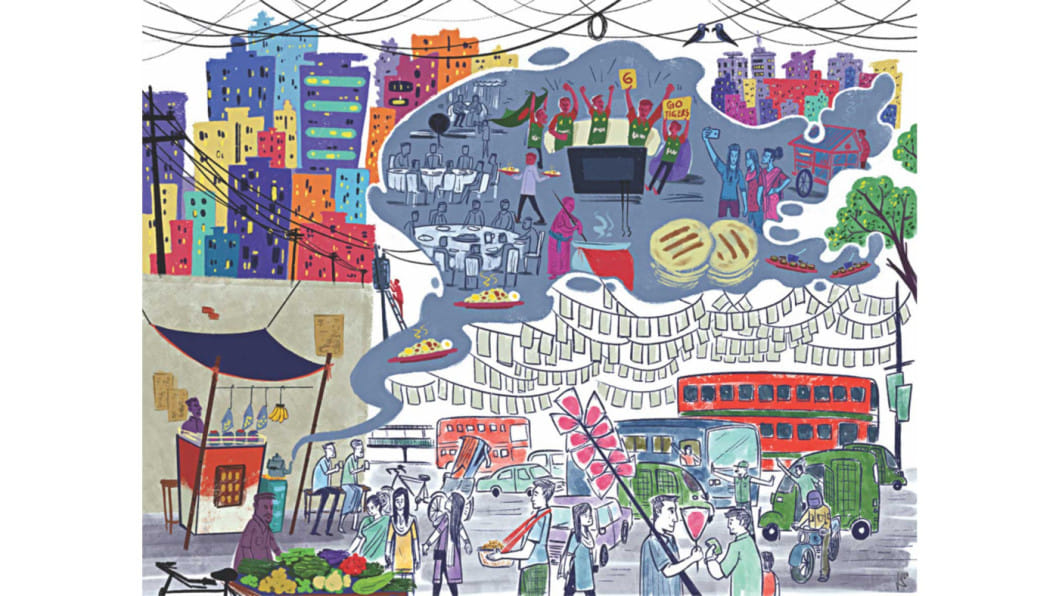

This is a friend who has visited Bangladesh for work a few times over the last several years, staying for a few months at a time. She moves around Dhaka by bus, laguna, rickshaw and boat. She has spent the night in a bosti and fails to understand why others are surprised at that. She finds the simplest hole-in-the-wall places to eat and appreciates the quality of their daal. She suffers, of course, from the traffic and the heat, but the other impressions—the vibrant colours, the flavours of the food, the friendliness of the locals, the lush beauty of the countryside—all seem to make a greater impact.

We recently attended a wedding together. She had hoped to go to a beauty salon so that experts would wrap her saree for her, but the salon in question was closed. She then found an instructional video on YouTube and spent the next 45 minutes cursing the slippery georgette saree and the saree instructor, particularly when the instructor cheerfully commented that fixing the pleats was easy.

Of course, as a six-foot tall blonde woman wearing a beautiful saree, most people were not concerned about whether she had gotten the pleats right. At the venue, she greatly enjoyed the biriyani and borhani as well as conversations with bright young locals.

I watch her in admiration, but also can't help reflecting on how it can be easier for a foreigner to love this city than for the locals. I just finished Orhan Pamuk's "Istanbul," where he writes about how the locals simultaneously wish to become more Western/modernised and long for something that makes them uniquely Turkish, and how the prevailing dirt and poverty depress people. Something similar seems to operate here, where people are too busy feeling embarrassed about the traffic, the dust, the filthy air and the chaos even to notice the many charms that Dhaka has to offer. For so many people, modern means Western. Out with the rickshaw, in with the private car. Ban the street vendors and promote supermarkets. But the final achievement will never be a faithful copy of a Western city, but in the attempts to achieve it, much that is valuable will get destroyed.

On our way to the restaurant where we had lunch, we had to take several detours due to the overflow of worshippers at Friday services. We ended up leaving our rickshaw and having to walk farther than if we had just done the whole trip on foot. Then again, we got to wander down unknown lanes and alleys and enjoy asking people for directions. We savoured their visible pleasure at directing two bideshi. The sun didn't reach the back streets; it was midday on Friday, so traffic was still light. So both being pedalled on the rickshaw and wandering the lanes on foot was actually pleasant. I commented on how hard it was to agree with the common assessment that Dhaka is one of the world's least liveable cities.

"I guess it depends which part of Dhaka," my friend suggested.

Partly that, yes, but it also depends on our perspective. Are we dreaming of another place and constantly holding Dhaka up in comparison and cataloguing its shortcomings? Or are we actually paying attention to what makes the city pleasant and distinctive—its own place rather than another imitation of a tired model that brings its own costs and downsides?

Strolling at a lake, riding on quiet streets on a rickshaw, watching small groups gather at a tea stall, enjoying savoury street food, hearing the excited shouts of children playing outside—all those moments bring home to me how lovable Dhaka—and Bangladesh—can be.

But sometimes it takes an outsider to remind us.

Debra Efroymson is the executive director of the Institute of Wellbeing, Bangladesh, and author of "Beyond Apologies: Defining and Achieving an Economics of Wellbeing."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments