Looking beyond the official arithmetic of inflation

Do the official inflation figures in Bangladesh reflect the actual inflation faced by the economically marginalised households in the country?

The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) calculates the official inflation rates in the country. It constructs Consumer Price Indices (CPIs) for national, rural, and urban areas, and calculates inflation rates for these areas using the respective CPIs. The reference groups for the constructed CPIs are the average urban and rural households of Bangladesh. The consumption patterns of these households are derived from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) of 2005-06. In the urban consumer basket, 422 commodities are included, while the rural basket consists of 318 food and non-food items. Using the data of HIES 2005-06, the BBS derives the weights of items in the baskets based on the average expenditure incurred by a household on the item, expressed in terms of its percentage share in the total expenditure on all items.

There are two major concerns related to the process of the BBS's estimation of CPIs and inflation. First, it is difficult to understand why the BBS is still using the 2005-06 HIES data to derive the weights of the items in the consumption baskets, whereas the latest data, HIES 2016, has been available since 2017. It is quite reasonable to argue that the food habits of people in Bangladesh—both poor and non-poor—have changed since 2005-06. But these changes are not addressed while calculating the CPIs by the BBS. Second, and more importantly, the CPIs calculated by the BBS hardly reflect the inflation faced by low-income households in Bangladesh—in both urban and rural areas. The average consumption baskets used by the BBS to calculate the CPIs are not truly representative of the consumption pattern of many low-income households.

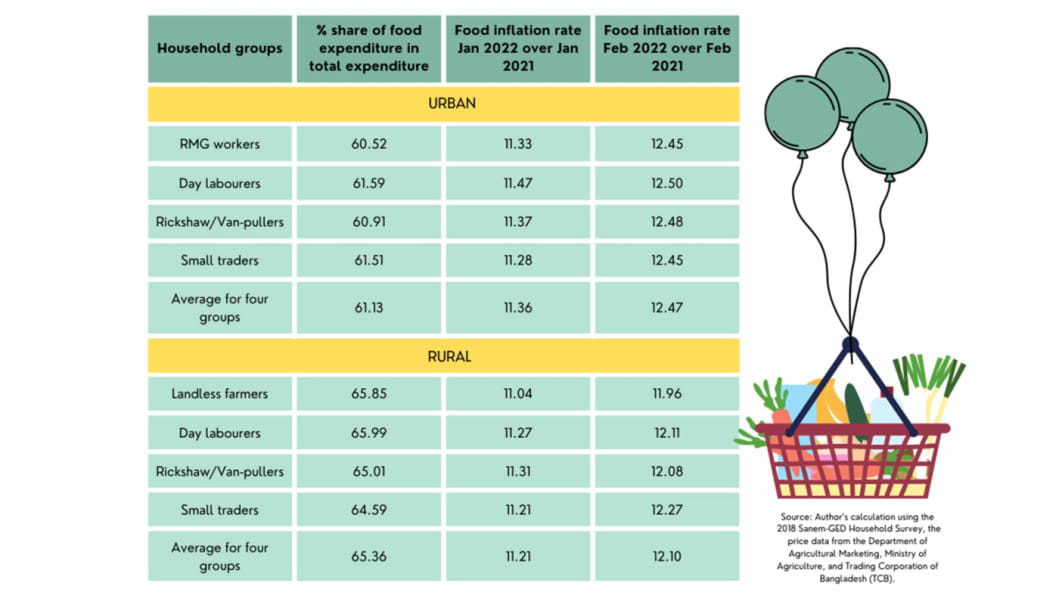

Therefore, the official figures of inflation do not reflect the reality of the marginalised households—the stress that they suffer—in the wake of price hikes. In this exercise, we offer an alternative estimation of the inflation rates for such households. We have identified eight marginalised household groups in Bangladesh, who are vulnerable to food insecurity due to the rise of essential food item prices. In the urban areas, these household groups are ready-made garment (RMG) workers, day labourers, rickshaw/van-pullers, and small traders. In the rural areas, these groups include landless farmers, day labourers, rickshaw/van-pullers, and small traders.

We have constructed CPIs for each household group by using the detailed and disaggregated data of the nationwide survey of 10,500 households, conducted by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem) and the General Economics Division (GED) of the Planning Commission of Bangladesh in 2018. From this survey data, typical food consumption baskets of these eight household groups are constructed, and respective weights of items in the food baskets are calculated. Using these food baskets, the monthly point-to-point food price indices and food inflation rates are calculated based on retail price data collected by the Department of Agricultural Marketing under the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Trading Corporation of Bangladesh (TCB). The results are striking!

First, food consumption baskets of the selected marginalised household groups are concentrated on much smaller items than the food baskets used by the BBS. Second, the average food consumption is 61.13 percent of the total consumption expenditure of the urban marginalised household groups, and 65.36 percent of the total consumption expenditure of the rural household groups under consideration. These are much higher than the food shares used by the BBS in their CPI calculation: 45.17 percent for the urban areas and 58.54 percent for the rural areas. Third, the calculated average food inflation rates in February 2022 for the marginalised households under consideration in the urban and rural areas are 12.47 percent and 12.10 percent, respectively. In January 2022, these figures were 11.36 percent and 11.21 percent, respectively. This suggests that not only the food inflation rates have increased in February, but the rates are also much higher than the official inflation figures. For example, in January 2022, according to the BBS, the food inflation rates for the urban and rural areas were 4.85 percent and 5.94 percent, respectively. However, our estimation suggests that the marginalised households in Bangladesh are facing food inflation rates that are more than two times the officially reported food inflation rates.

Inflation is the "cruellest tax" for marginalised people. Our analysis shows that the officially reported food inflation figures are grossly underestimating the actual food inflation faced by financially marginalised households in Bangladesh. Due to the high reliance on the necessary food items, poor people cannot cut down on necessities and are hit the hardest by the soaring prices of necessities. The policymakers in the country need to address this concern with utmost priority.

Dr Selim Raihan is a professor of economics at Dhaka University, and executive director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments