No real social change comes on its own

Every new year brings new hope in our lives. We hope that things will finally change. But things do not, they stay the same, and we despair of ever finding change until another new year comes and ignites our hope again. The reason behind this, in short, is a disease that our society and state have long been infected with: capitalism. Our effort to rid ourselves of this disease through political means has been persistent, as has been our failure. It's evident everywhere you look. From the prices of goods to a general lack of security in every aspect of life, the markers of this failure are clear for all to see. We have become accustomed to this—until an incident here or there jolts us awake, making us realise that we're in trouble.

Let's talk freedom. The question over individual freedom is an old, if recurring, one, but it should have been settled by now. There should have been no doubt that "freedom" and the "freedom of expression" are the same thing. Without the freedom of expression, democracy is just a fiction. In our so-called democratic state, the duties of the members of parliament should have been to pass appropriate legislation, establish control over the executive branch of the government, hold the government accountable, ensure transparency in the activities of the executive branch, and scrutinise the government's foreign policies and agreements. But they are doing none of these, not in the slightest.

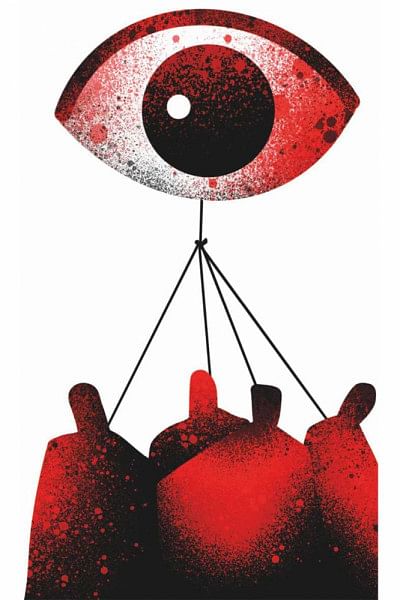

Criticism of mistakes made by the government is part of the democratic process. But our rulers cannot tolerate even a hint of criticism. They are too sensitive about it. The reason for this is that they do not have a solid moral footing. They know how they have come to power, and when power is monopolised like this, it is natural to lose people's support. Our rulers only serve their own interests, not the interests of the people. Hence, they are easily disturbed by criticism. It makes them feel vulnerable. It makes them fear that their downfall may not be far away.

Part of their strategy is to make noise—a lot of it. So some of them say they will not rest until they bring about "change"; others claim that people will be blown away by a surge of prosperity and dance in joy. No matter which government is in power, they want to drown any sound of criticism with their own noise. They are quick to reject, choke or silence any voice critical of their actions or lack thereof. Their hostility towards critics gives the impression as if they think that since they have acquired the right to rule, they should be the ones making all the noise. There is an element of self-deception in this pattern of thinking. They hope that only their noise, and no other sound, will be echoed.

It's not like the ruling party always speaks in one voice. You can hear a variety of contrasting opinions from within the ruling camp. For example, when the current government came to power, one of the ministers said they would be able to control the prices of commodities through the intervention of the state-run TCB. Almost immediately, another minister spoke in favour of keeping the market open, saying a free market would bring down the prices. Consequently, the TCB remains stuck in no man's land, and prices have not gone down at all. In fact, the steady rise of prices has left the people overwhelmed.

The effective role of opposition is vital for a parliamentary democracy. But the history of our country tells us that no opposition party has been able to carry out its responsibility so far. Often they faced obstacles created by the government, while also lacking the moral strength to overcome that. They also lack acceptability among the people. In a situation such as this, whatever valid criticism we see comes from the people. Silencing their voice is tantamount to establishing dictatorship.

While the media is being subjected to covert and overt threats, the current government passed the Right to Information Act, 2009, the apparent objective of which was to empower that very media and bring about transparency and accountability within the government. Such contrasts between the real and the legal are not uncommon. Apparently, there was pressure from the so-called international community to pass this legislation. It is not difficult to assume that this law will be of no use to the people while the government shows no tolerance for any form of criticism. The ruling class is averse to any expression of people's grievances, let alone any suggestion of empowering them, which it is pledge-bound to do.

Under these circumstances, it is important to apply pressure to make the government become tolerant. There are two vital sources of pressure here: the first, of course, is the public, and the second—and more important one—is an alternative democratic political power. Developing the latter is a time-consuming process. But the people can quickly organise themselves for a common cause if they are united.

In the Pakistan era, we saw how united journalists were on the question of the freedom of the press, and how any assault on newspapers would ignite nationwide protests. That unity does not exist anymore. The ruling class has been able to create divisions within the journalistic community, and the media is haemorrhaging as a result.

The practice of culture and literature, even of journalism, requires a material foundation which is not strong in Bangladesh. There is no indication that the new year that we have started will reinforce that foundation. A big problem here is lack of investment. Investment is not growing. There is fear that the remittance sent by our migrant workers will soon shrink. A number of mega projects have been undertaken which involve big spending. But instead of generating value, it's more likely that there will be wastage.

One example of this is Dhaka's flyovers. Experts say that instead of reducing traffic congestion, these will rather increase it. Pedestrians and ordinary public transport users will see little change in their luck while the benefits will be enjoyed by motorists. Almost all big cities in the world have moved away from the idea of flyovers, except for Dhaka. The solution to traffic congestion is metro rail, which is now seen in all big cities including Kolkata. Dhaka also needs metro rail, and it's a good thing that the construction of our first rail is underway. Once the construction is over and the metro rail gets functional, we will know how beneficial it is.

Going back to the question of freedom, it's essential to change our current system for our collective freedom. But this hasn't been possible as yet. Whatever prosperity there has been is enjoyed mostly by a few people, and even those are not safe either. Most people are spending their days in hardship and danger. There is no doubt that we can't change this system with individual efforts alone. Even a political movement cannot do anything about it. However commendable these isolated efforts are, what we really need to effect change is a collective and continuous socio-political movement guided by clear objectives. If we can't do that, we won't be able to live like we want to, and we will remain half-dead, like we are now.

Serajul Islam Chowdhury is professor emeritus at Dhaka University. The article has been translated from Bangla by Azmin Azran.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments