Perils of global capitalism: What’s next?

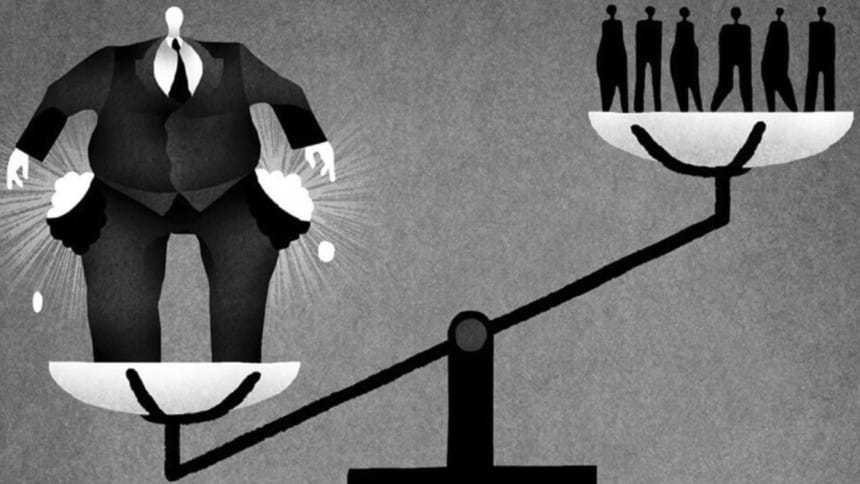

In my recently published book, "Markets, Morals and Development" (Routledge, UK), I discussed the discontent with the contemporary global economic order that is prey to the excesses of market supremacy and beholden to private corporate interest. This is an economic order characterised by instability, mass human migration driven by wars and destitution, and unprecedented wealth concentration amid widespread poverty, posing threat to the very sustainability of our planet's health and habitat. Some of my academic colleagues have taken me to task for skilfully avoiding the difficult question of what the ways out are, while pointing to the fallibilities of the system.

The book does discuss the moral case of income redistribution beyond the usual debate about economic consequences of redistributive policies, and quotes Cambridge economist Sir Partha Dasgupta as saying that no country is so poor that it does not have the means to provide for the basic needs of its entire population. The moral case I made rests to a large extent on the fact that the element of luck plays an important role in income distribution, which is underplayed both by pro-market conservatives who extol the virtues of entrepreneurship and effort, and by left-leaning progressives who put the blame of inequality entirely on the processes of the market economy. Poverty in a market economy may simply result from economic failure due to bad luck, so society has a moral duty to provide "insurance" for such failure. Similarly, much of the wealth concentration may be due to rent-like income earned by luck—and not necessarily through entrepreneurship alone.

This later aspect of inequality points to the possibility of redistributing not only income, but income-yielding assets as well, without doing much harm to entrepreneurial incentives. For this, the example of China is not of much help either, given that income inequality there has risen phenomenally from the pre-reform days of the 1980s to the present. This shows that even a communist political system cannot be immune to private income and wealth concentration once the forces of the market economy under private ownership are unleashed. Besides, a totalitarian regime with minimal human rights is not an ideal example to imitate.

In fact, a clue does already exist—even if it may only be in the form of a conceptual model. The idea is about how to combine a mechanism for generating enough public funds for a welfare state and thwart any unmitigated concentration of private wealth, while also harnessing the strength of the market economy. The failure of the Soviet experiment of a command economy and the contemporary economic success of China have proven the essential role of the market and private entrepreneurship in achieving economic prosperity. On the other hand, the debates about the pros and cons of income redistributive policies do not provide much guidance regarding how to contain the increasing economic power of corporate business that corrupts democracies and prevents undertaking of any deep welfare-oriented reforms, whether for removing global poverty or protecting the environment.

The new economic arrangement I am alluding to originates from a relatively little-known book published in 1964 by Nobel laureate economist James Meade, titled "Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property." In this book, he proposed what he called a "property-owning democracy," in which a state investment fund may be created to acquire portfolios of assets through acquisition of business shares—"topsy turvy nationalisation," in his words—and by appropriately designing an inheritance tax. The return on these assets could then be used as a social dividend or basic income for the poor. This, he argued, would avoid the entrepreneurial disincentives created by income redistribution through high income taxes. While the social democrats in the UK toyed with this idea in the 1980s and the 1990s, it became a "lost perspective" afterwards.

Ironically, the idea of public asset ownership was revived by the ultra-conservative administration of US President Donald Trump, when it proposed to take equity stakes in Covid-impacted companies as a condition to providing economic assistance—"equity for a bailout," in common parlance. Earlier, during the financial crisis of 2008-09 in the US, the financial bailout of General Motors also involved acquisition by the US treasury of non-voting company stocks. In the deeply rooted culture of Western capitalism, these measures were conceived as only temporary, with the idea that the government would opt out of asset ownership as soon as the companies came out of the debt repayment and liquidity crisis.

However, the scope for experimenting with such a model is much wider in many less developed countries. With rampant capital flight in these countries, many well-run private businesses fall into debt repayment crisis—not because they are not profitable enough, but because the profits are expatriated abroad. The governments are forced to bail out these companies by various financial assistance, like allowing additional loans and rescheduling existing loans at concessional interest. The interest rates on these loans in real terms—that is taking inflation into account—often turns out to be negative, thus putting a heavy burden on the financial institutions and harming the economy at large. The government can, instead, salvage the companies by acquiring dividend-yielding assets, and create a public trust to spend the income from the dividend on public welfare activities.

This model of a welfare economy—let's call it "democratic shared capitalism"—would admittedly appear to be rather utopian, as Meade himself thought his idea of "property-owning democracy" was. The economists once advocating the so-called "Washington Consensus" doctrine of "privatise, liberalise" will be horrified at the notion of going back to the era of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). These SOEs were not only used to be ill-managed because of a lack of profit-maximising incentives of the government functionaries who ran the SOEs, but they also proved to be a drain on public resources and were treated by bureaucrats and politicians as a means of extracting all sorts of benefits.

The idea proposed here will work only with a deep political commitment and a fundamental change in the mindset. The management of the companies in which the government will acquire stakes will have to be allowed to operate completely independently, like any private business, while the performance of their management will be judged purely by their performance in maximising shareholder dividend—albeit under the usual market regulatory framework. That sort of change in mindset will not come in a situation of business as usual, but may only happen at a time of crisis when a regime comes to realise that its very legitimacy and viability are at stake, and that it should leave a legacy for the future. Who knows a new and more humane model of market economy will not arise from the Global South that is in transition, rather than from the mature capitalism of the North with its general abhorrence for such "statist" ideas?

Dr Wahiduddin Mahmud, a former professor of economics at Dhaka University, is chairman of the Economic Policy Group in Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments