The Definitive Story

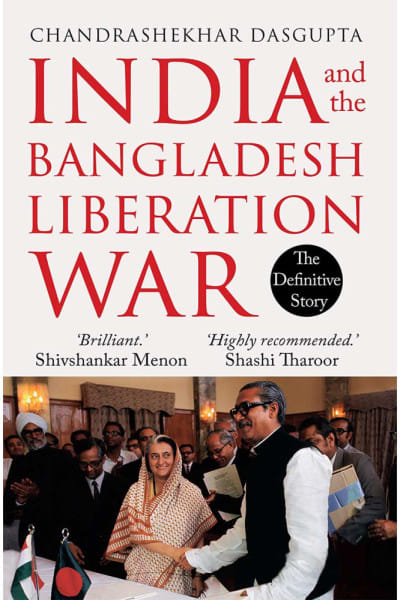

Retired Indian diplomat Chandrashekhar Dasgupta's recollection of the events of 1971, centring on the Bangladesh Liberation War as captured in his recently published book, India and the Bangladesh Liberation War: The Definitive Story (juggernaut, 2021), is indeed what the sub-caption of the book suggests—it is arguably the most definitive story. As the author says in his introduction, the book is not about the military operations of December 1971, nor is it a global history of the war; it is about India's grand strategy in 1971 and how this was played out comprehensively and in a seamlessly coordinated manner, employing all the resources available to a state—diplomatic, military and economic—to achieve a political objective.

Dasgupta highlights that even the absence of an institutionalised coordination mechanism in the establishment did not stand in the way of its execution. Going through it, any reader would agree that the book is the product of lengthy research by, and sheer perseverance of, the author. This explains the minute details of the events of the period, both inside India and in the international arena. Dasgupta goes to great lengths to talk of the interactions and discourse between and among the major stakeholders—the government of India, the Bangladesh government in exile and the key players in the global arena. Dasgupta's emotional attachment to the events is perhaps explained partly by his personal experience of being among the first few Indian diplomats to be assigned to the just-opened Indian diplomatic mission in Dhaka—an assignment any Indian diplomat would have coveted and cherished—and partly by his own desire to understand, and record, the entire gamut of what transpired at various stages during the nine months between March and December of 1971.

The book is, at once, illuminating and instructive. It starts off with a potent quote from Bengal's highly-revered political leader, Abul Mansur Ahmad, on how little there was in common between the two wings of Pakistan. This reflects Chandrashekhar Dasgupta's deep insight into the political, social and cultural reality of Pakistan. In the opening two chapters, Dasgupta expands on Ahmad's quote to understand how the fissure that existed at the country's very birth, tectonically morphed into a gaping fault line and then led to its inevitable disintegration, and how Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a central figure in this historic passage. An entire chapter is devoted to the Bangladesh Mukti Bahini; its birth, its growth and its critical role leading to the final liberation of the motherland.

During the nine months of the Liberation War, that Pakistan's military leadership, and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, had their heads buried in the sand is all too well-known, that the Nixon administration—especially his principal analyst, Henry Kissinger—got it all wrong from the very beginning is also clear, and that, in the end, China's posturing for Pakistan would not be matched by any military action also became evident. The book graphically elaborates on all of the above in finer details. What is illuminating in the book is its descriptive revelation of the process of convergence of minds between India and the then Soviet Union. This was not a given, as many erroneously thought it was. Dasgupta writes in great detail about how the process evolved. No denying that the prevailing Cold War played its part in this, but the driving force behind it was India's well-choreographed diplomacy, anchored by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi herself, aided as she was by a highly-astute team of technocrats in the persons of PN Haksar, DP Dhar, TN Kaul, RN Kao, et al. The passage of the Soviet position—from one of initial circumspection to that of an ally, culminating in the historic Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation in August 1971—was clearly the outcome of deft diplomatic handling by India and an equally mature response from Moscow. Dasgupta carries the reader through the entire process of negotiations step-by-step, with focus on dealing with the tricky Article 9. The Treaty was a game changer in more ways than one. It hardened the Soviet stance towards Islamabad, starting with cutting off arms delivery. Dasgupta amplifies this in Chapter 10 where Andrei Gromyko, the crafty Soviet Foreign Minister, made it known to the visiting Pakistan Foreign Secretary Sultan Mohammad Khan in September that Moscow's words to the Pakistani leadership to not provoke a war with a treaty partner and to ensure the safety of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was not a request. The strategically important convergence between India and the Soviet Union also gave the Nixon administration and China enough food for thought. For one, it served India to use this convergence as a countervailing tool against the emerging Sino-US entente. It also enabled Mrs Gandhi to talk with the leaders in Washington, London, and in other Western countries from a position of confidence. Importantly, it caused Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to recognise that the Bangladesh freedom struggle was a war for national liberation and also of the crucial role the Bangladesh Mukti Bahini played in this process.

The author quotes a senior Indian diplomat involved in the earlier stages of the negotiations, who aptly commented, "Article 9 has just the right amount of substance and shadow to confound our enemies and hearten our friends."

In the book, Chandrashekhar Dasgupta explains that the impact of India's role in the Bangladesh Liberation War, besides changing the geographical and political landscape of South Asia forever, was also felt on the critical issue of Kashmir between India and Pakistan. An important outcome of the 1972 Shimla Summit between the two countries was an agreement to take the issue out of the ambit of any multilateral framework (read: the UN) and confine it to bilateral arrangements. It also led to a rearrangement of the Line of Control in Kashmir.

Chandrashekhar Dasgupta's book derives its strength from the fact that it is based on indisputable evidence, irrefutable logic and undeniable truth. It is objective, succinct in both its form and content, easily readable and even easier to absorb. The book also reaffirms the point made by current Indian External Affairs Minister Dr S. Jaishankar in his own book, The India Way, that India's role in the Bangladesh Liberation War was the former's greatest diplomatic and military triumph.

One could be excused for wondering why it took so long for such key details to emerge in their totality. The counterargument would be that the timing of the book's launch coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Liberation War of Bangladesh, and India's decisive role in it, makes the whole exercise more relevant.

Former Indian Foreign Secretary and National Security Advisor, Shiv Shankar Menon—undoubtedly one of the finest minds in India's foreign policy establishment—describes the book in one word: "Brilliant." He goes on to add that it is a must-read for scholars of history and geopolitics, diplomats and anybody willing to study the emergence of a different South Asia. Chandrashekhar Dasgupta's masterful scholarly work is all that, and then some.

Shamsher M Chowdhury, BB is the former Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments