Understanding the tragedy of August 15, 1975

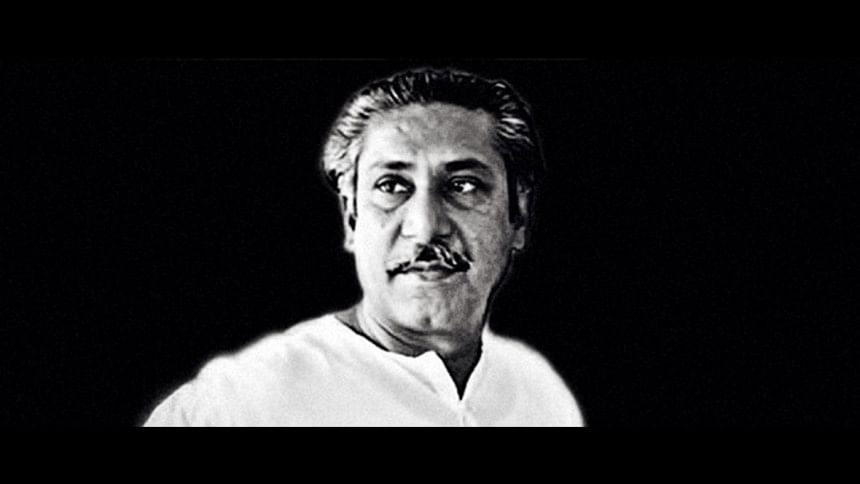

All Bangladeshis, particularly those born after 1971, need to know and understand why the ghastly assassination of Bangabandhu on August 15, 1971, is such a massive tragedy. The significance of this appreciation lies in the unfortunate attitude of some quarters in seeing and evaluating Bangabandhu through the lens of political partisanship. The fact of his being the supreme leader of a political party that largely spearheaded our struggle for emancipation cannot mislead us into ignoring the epic dimension of his momentous contribution, and how his premature demise has adversely impacted the body politic of Bangladesh.

Very few would dispute the fact of history that Bangabandhu transcended conventional political reckoning and became a symbol in his own lifetime. His persona embodied an appeal that distinctly transcended class-barriers, and history chose him to lead our struggle for emancipation. In 1971, all Bangalis needed an extraordinary leader as the symbol of their aspiring nationhood and Bangabandhu fearlessly performed the catalytic act of political entrepreneurship required to forge a nationhood.

Bangabandhu's message after March 1969, was, quite clearly, to drive home the reality that Bangalis not only were separate in their social, political and economic life from Pakistan, but that as one people, they had to proclaim the right to live a separate life from West Pakistan. It was Bangabandhu who made the military junta and West Pakistani leaders realise the "seismic changes which had been registered in the self-awareness of the people of Bangladesh between March 1969 and March 1971". The new-found sense of nationalism gave rise to demands for full political independence.

It is an undeniable fact of history that for the Bangalis, "national sovereignty was inculcated into the consciousness of the masses through a deliberate process". This building of national consciousness was the result of Bangabandhu's epic organisational acumen. In fact, Bangabandhu came to personify Bengali nationalism, "just as Nasser personified Arab Nationalism". The different aspirations of all classes of Bangalis were focused on him for leading "seventy million people into the promised land".

The historical context cited above should convince all right-thinking persons into believing that the killing of the supreme leader of the freedom movement and in fact, the cruel silencing of the patriarch of our struggle for emancipation, was done to emasculate the nation. This diabolic murder was planned and executed by quarters that could not reconcile to the reality of Bangladesh and were determined to extract revenge for their ignominious defeat in 1971. The proof of this belief laid in the fact "that since 1975, we have witnessed the resurrection of those very forces which remained deeply inimical to the historical processes which shaped the emergence of Bangladesh".

The tragedy of August 15, 1975, "lies in the fact that… [the] symbol of our nationhood was not only assassinated but was marginalised from our historical consciousness for 21 years. This single act of terrorism did not just murder a leader and his family, it was an assault on the inspirational sources of our nationhood for which we have paid an incalculable price".

Dispassionate analysts have to agree that the gory events of August 15 and the malevolence in granting the legal immunity to the killers were a crude assault on our jurisprudence in addition to being a satire on humanity itself. Perhaps some quarters still do not realise how low we stooped in the estimation of the civilised world when the then ruling cabal decided to insert this shameful piece of legislation in our statute book. We have to only thank ourselves for the emergence of a sane political environment when this ignominious piece was struck-off.

The cruel assassination of Bangabandhu tragically impacted the process of transfer of power and the legality of the assumption of political authority was thrown to the winds. It is thus no wonder that the nation had to witness a series of military coups and counter-coups from 1975, leading to the bloody assassination of the head of the state in 1981. The compounding tragedy in this process was the loss of many promising military officers. Quite a number of soldiers were also executed without the benefit of a reasonably fair trial. Hapless Bangladeshis could see manifest arrogance at play to seize power by the sheer use of force.

The above illegal use of force to capture state power was on blatant display once again when in March 1982 the military usurper interposed between the nation and the polity as a great historical aberration. This was a time when Bangladesh's institutional decay started acquiring an ominous pace. Terms like "election engineering" came into circulation with many not realising the deep cracks occurring in the foundation of good governance.

The post-1975 governments in Bangladesh mischievously tried to demean and belittle Bangabandhu's accomplishments in governance by conveniently forgetting that in barely three years, nearly 10 million refugees had been resettled and a famine was averted, considerable progress made in restoring transport operations, most of the severed links restored at least on a temporary basis, and most importantly, handling of traffic at Chittagong Port was approaching pre-independence level. The production of Jute goods in June 1972 stood at 85 percent of the average 1969-70 level or at about 75 percent of the capacity. The World Bank reports of August and November 1972 testify to that.

Some quarters are oblivious of the fact that in July 1974, massive damage by a sudden flood of standing crops, estimated in the region of one million tons, was to create the condition which, "aggravated by the external factors… were to lead to the agonies of famine in the autumn 1974. The external factors which created this crisis and destabilised the state were to pave the way for the destructive assault that were to follow in 1975". Quite clearly, Bangabandhu was a victim of massive conspiracy.

Many in Bangladesh tend to forget that the fundamental task of structural change in agrarian sector could not be undertaken due to the political leadership's intense preoccupation with the urgent law and order issues and severe economic problems in the initial years. Structural change, to be effective, require a thorough reorganisation of the party, a process that could not pick-up momentum in the short period. However, Bangabandhu's signature achievement was in the making of a liberal democratic constitution, the holding of a general election and a general amnesty in November 1973 to the collaborators of the Pakistan Army.

Bangabandhu's magnanimity in advancing the interests of national reconciliation was not reciprocated as "many of the amnestied collaborators upon release began to undermine the unity that had been attained by rousing communal sentiment". We must not forget that it was due to Bangabandhu's stern and caring stand that a feared massacre of the collaborators did not materialise. His government very admirably took the firm position that collaborators would be dealt with in accordance with due process of law. Unfortunately, "a few summary executions carried out by some Mukti Bahini groups, however, received worldwide publicity". Nothing like the migration of two million collaborators to Canada after the American war of independence or the massacre of collaborators as happened in France and Belgium at the end of Second World War, took place in Bangladesh.

The overarching imperatives of public order and unhindered economic development in Bangladesh in mid 1970s may have given rise to the one party BAKSAL government, but it was not meant to be a permanent feature of political governance. Whatever may be the case, there cannot be any justification for killing Bangabandhu and his family, to restore or promote democracy, as many detractors wrongfully claim. Surely, the BAKSAL scheme could have been confronted in a constitutional manner. Sadly, annihilation of the opponent became the preferred option. The aberration that occurred with his assassination had deep-seated implications on the body politic and our democracy deficits has its root in that tragic event. Therefore, the murder of Bangabandhu was clearly a cardinal crime, ominously impinging on the ethos of our democratic progression.

Muhammad Nurul Huda is a former IGP of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments