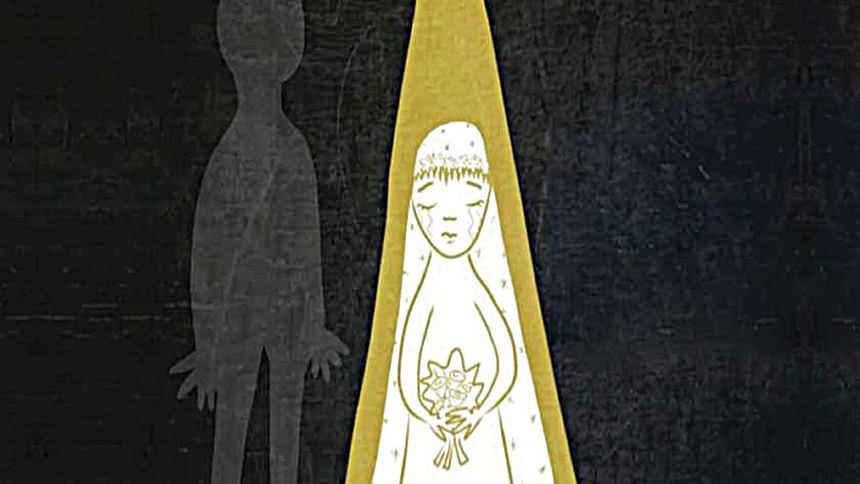

What does it say about our society when a child bride sets herself on fire?

Upon reading the news headline for the incident I am about to discuss, I only felt a momentary, dull pain in my gut or thereabouts. Because while it is a shocking incident that would rob you of hope, the elements of the story are all too familiar to us all.

A girl of 16 years—a college fresher named Suraiya Newaz Labonno—was married off in Netrakona, after which her in-laws demanded a hefty dowry. When her family was unable to pay the dowry, she was taunted by her in-laws constantly. A few months into the marriage, Labonno got pregnant. A year on and the taunting only worsened. In August, according to the news report, Labonno left her husband's home and moved back in with her parents.

But October 9 proved to be the last straw. According to Labonno's family, a visit from her husband—meaning renewed verbal and physical abuse to force her to pay up the dowry he had demanded—resulted in her dousing herself in kerosene and setting her own body on fire. Sustaining 90 percent burn injuries, Labonno gave birth to a stillborn baby on October 14. Twelve hours later, she succumbed to her injuries while on life support. As per a report by the daily Samakal published on October 16, her family filed a case against her husband and five other people, but no one was arrested at the time.

When all of this blows over, with or without justice, what happened to Labonno will be just another story—a statistic. But it does prove, once again, that when Bangladeshi women and girls face gender violence, it is usually from those closest to them and that it comes in more than one form at a time.

First and foremost, the fact that a person as young as 16 years was married off and also conceived a child soon after is not surprising in the context of our culture—especially given the rise in child marriage during the last year and a half of Covid-19 pandemic.

According to Brac's Gender Justice and Diversity programme, child marriage increased by at least 13 percent during the pandemic. Another assessment report by the rights organisation Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF) from March said that at least 13,886 girls in 21 districts became victims of child marriage between April and October of 2020; 48 percent of these girls were aged between 13 and 15 years.

This rise in child marriages starts making sense when one factors in the proportion of people who were pushed below the poverty line. According to a survey by the Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and the Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) from April 2021, at least 40 percent of our population may currently be living in poverty. This number was 20.5 percent before the pandemic hit.

Many people lost their jobs, and children of lower-income families—who did not have access to necessary digital learning materials—were kept out of school. In most cases, one of two things happened: either the child had no choice but to join the workforce to help out their family financially, or the girl child was married off by parents in the hope that their burden would lessen. But what happens when a girl's family marries her off while giving the impression that she is a kind of nuisance who is transferable and can be done without?

Usually, it prompts the girl's in-laws to also treat her that way. In most cases, the groom is much older than the (child) bride and much more capable of earning a living. This, coupled with the embedded patriarchal values in Bangladeshi families, puts the victim of child marriage at the end of the chain of both her families. Take into account the practically non-existent implementation of child marriage preventive laws in our country, and you have someone who is at tremendous risk of facing violence of any and all forms.

Unfortunately, the risk is a reality in the cases of many, if not most, child brides. Besides a halting of their education, other common problems they face include reproductive health issues due to early pregnancies, inability to acquire financial independence, loss of connection with peers (that is, having no personal social circle besides those approved by her family), dowry demands, and physical and/or mental torture by the in-laws.

It is not that laws are not in place to provide justice to the victims of child marriage—and of the resulting abuse. But that's just it: the laws mostly focus on getting justice to those who have already been made victims. Shouldn't our focus be on prevention as well? What is the point of harping about laws being in place after the fact? What use would it be to Labonno, for example, if her husband and others are now arrested and punished under the Dowry Prohibition Act or the Child Marriage Restraint Act, when her life and ambitions are already lost?

The years of advocacy and rectification that have gone into forming these laws must be appreciated. However, punishment of crimes committed against child brides does not solve the issue of why there are still so many child brides in our country. Even before the pandemic, over half of the marriages taking place in Bangladesh were cases of child marriage, according to the United Nations.

As already mentioned, poverty plays a major role in perpetuating the practice of parents marrying off their daughters under the age of 18 years. But there is also a major lack of awareness about the dangers of child marriage; too many aspects of our society also help enable this practice.

In April 2020—the month after the first case of Covid-19 infection was detected in Bangladesh—the Child Helpline, 1098 (run in collaboration with Unicef), received at least 450 calls relating to child marriage, as per a Dhaka Tribune report from March 2021. Most of these calls were from adolescent girls afraid of being forced into marriage. So, even though young people—and child brides themselves—are aware that what is happening to them is not normal, it is because of the lack of awareness of those who surround them that so many child marriages take place in Bangladesh every year.

It is up to the state, the rights groups, and the community leaders to raise awareness and conduct dialogues regarding how unfavourable a fate the victims of child marriage usually meet. Families must be made to see that it would be far more beneficial for them to let their adolescent daughters stay in school and pursue their own careers in the long run. Otherwise, these child brides will continue to be subjected to violence and will find it easier to escape abuse by death than by law.

Afia Jahin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments