Abahani vs Mohammedan: Worth gold in nostalgia

Almost every major football crazy city in the world has a historic club rivalry that it can brag about. Kolkata, London, Manchester, Milan, Madrid – you name it and there's at least one colourful and storied rivalry to whet the appetite of football fans.

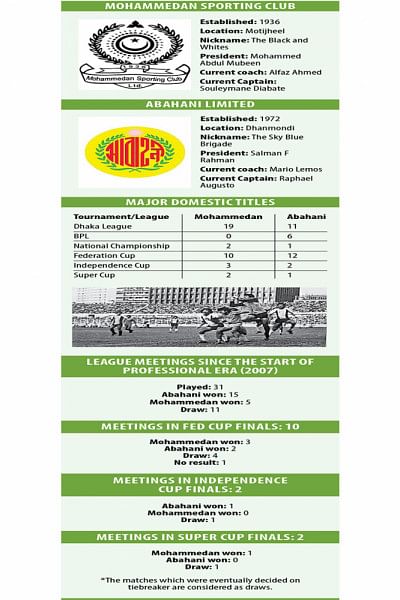

Dhaka, our capital, had one such rivalry too which could rival those of the aforementioned cities for passion and excitement in its heyday. I say Dhaka had - as that rivalry, the one between Abahani and Mohammedan, no longer evokes the passion and excitement it once used to.

The Dhaka Derby, as it has come to be known in modern footballing parlance, is now a thing of nostalgia for those who witnessed the raging domestic football craze in the '80s and '90s of the last century. It is more alive in memories and memoirs of the football fans than on the pitch.

I can consider myself fortunate to at least have some fading memories of those wonderful times when the whole weeks or months would pass in anticipation of a Dhaka Derby. Not that the other league or cup matches were of less significance, however, the Dhaka Derby always had a special place in the hearts and minds of the football aficionados.

The Dhaka Derby started to catch the imagination of the nation long before televisions made their way into our living rooms. Radio was the go-to medium for the majority to turn to for the action. And the running commentary -- with the baritone Abdul Hamid, the eccentric Khoda Baksh Mridha, the poetic Nikhil Ranjan Das and the meticulous Tawfiq Aziz Khan – relaying the riveting action from behind the microphone made the experience all the more memorable.

The memories of those days for me are a little vague, for I was too young when the Dhaka Derby was garnering unparalleled attention. Yet the recollections and reconstructions of those times tell me that we used to zoom over the radio long before the games started and kept on tuning until we received a decent signal. The games used to take place in the afternoons, and our afternoon sporting adventures were thus off the chart for those special days. It was perhaps a shared experience between all children and youth in our neighbourhood, encapsulating the entire city for that matter.

Then came television and the Dhaka Derby became more tangible for those like me, who had never had the chance to go to the stadium since the atmosphere there was deemed too rowdy for the young ones. Names such as Salam, Aslam, Badal, Chunnu, Gaffar, Iliyas, Mohsin, Kanon, Munna, Sabbir and many others, whom we had only heard of or had seen pictures of in newsprint, became living heroes, or arch enemies, depending which side of the Abahani-Mohammedan divide one stood.

Back then, Bangladesh Television beamed a range of wonderful football coverage, including Road to Wembley – an FA Cup highlight show and later a Serie A show, probably featuring the best match of the week (remember, Italian league was the best in the world those days) – but Dhaka football, and more precisely the Dhaka Derby, continued to cast its spell on the audience for the entire 80's and major part of the '90s.

And after matches, we would wait impatiently for the elders to return from the stadium with a bag full of anecdotes of the game, the brawls, the atmosphere, and things like what happened to that odd Abahani fan who ended up in the Mohammedan stand.

But slowly, unbeknownst to us, the domestic game started losing its appeal and the Dhaka Derby slowly started occupying less space in people's minds and in news coverage.

It's hard to ascertain exactly when domestic football lost its charm and what exactly reduced the Dhaka Derby to a mere news item, but the common perception is that there were quite a few debilitating factors at work around similar time. Wide access to live European football through satellite television, cricket's commercialisation in the subcontinent and Bangladesh's relative success in the game and, most importantly, the national football team's continued failure – all these factors might have played integral roles in the decline of popularity of the domestic game.

What remains today are memories of those days to reminisce and goad about while the galleries remain largely empty when these two giants take on each other.

Sometime in the mid '90s, probably after a league title won by Abahani, one of our next-door neighbours hung a Sky Blue flag on the concrete walls of his rooftop water tank and emblazoned the words 'Abahani Krira Chakra' in bright and yellow Bengali fonts.

The flag has disappeared a long time since. No-one flies those Black and White or Sky Blue flags anymore; their place is occupied instead by the Sky Blue White of Argentina or the Green and Yellow Brazil like a ritual every four years.

Ironically that writing on the rooftop water tank is still there. Somewhat faded and unattended to for a long time, yet it's there, overlooking the neighborhood, reminding everyone of the heyday of the game, like the way a decrepit aristocrat would cling on to his last treasure to goad of his rich family legacy.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments