A compartment of their own

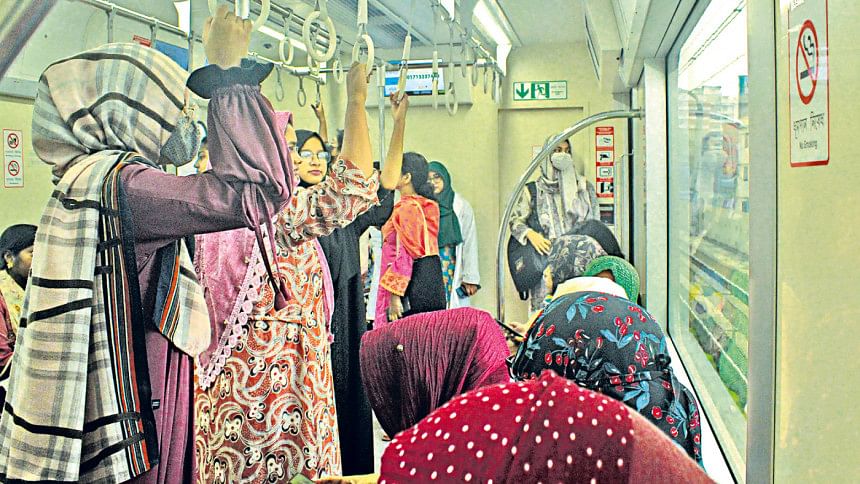

I remember the first time I stepped into the female compartment in the metro, I knew this marked a significant difference in the commute experience of women. Growing up in this country, public space posed an eternal threat. Alongside learning how to do subtraction and addition, girls grow up learning how not to disturb the dynamic of that space. And in that algebra, public transportation works as the key mechanism of reminding a woman of her place in society.

So, it meant more when this time around I boarded the metro at Kazipara station.

Kazipara Metro Station re-opened on September 20. It's been two months since its closure. Two months is a lifetime, it feels.

There were no signs inside the station that carried evidence of the July-August uprising. But, the moment one came out of the station, the graffiti would recall what had happened. What had happened was a fascist fell, and in place of that we have a new hope, a hope for a better country.

In this newfound landscape of the country, women are now facing newer and fresher assaults each day by people who suddenly feel empowered to instill their view of the world that much more violently.

So, now when 8:00am strikes and I get on the female compartment of the metro, all ready for work, I see and feel the importance of a metro in my life more.

And I am not the only one.

Nora, 16, a student of Tejgaon Government High School, is one of the familiar faces who boards the metro at the same time as me.

"Mom used to drop me off and she had to wait in front of my school with all the mothers. When the metro was inaugurated mom got our metro cards and after one or two transits, I started coming to school on my own," she said.

"I used to feel really bad for mom as she had to run with me wherever I went and then return home to take care of all the household chores. But now, me and my friends feel safe travelling in the female compartment," she added.

She looked at her friends and they giggled, immediately creating an aura of joy and I knew the comfort it stemmed from.

Mita Sarker, 27, goes to office in the Karwan Bazar area. Earlier, she had to take a bus that would require at least an hour to reach her office from Mirpur.

"I like this feeling of not being observed, stared at," she said. "I've always had this lingering fear that a false sense of security would lead me into a space I shouldn't be in and I would be one of those next-day news stories," she added.

"This sense of safety that I feel while I'm in this compartment is not false," Mita said smiling.

The test of freedom and safety is to see if it is granted. Dhaka metro's female compartment, in my experience, is the first public space where safety is granted.

When the rush of the office and school-going commuters subsides, a relatively less crowded female compartment offers a different kind of pleasure. As the metro rushes through Dhaka, oscillating between light and darkness, kids run around the compartment. Their mothers sit relaxed and the fellow travelers grant sweet mischiefs of kids with approving eyes.

Noori Shams, 60, was on her way to her son's house in Motijheel. Smiling warmly at the children running around, she shared, "I have a grandson. I used to need someone to accompany me to my son's house, but now, after finishing my morning routine, I hop on the metro and spend most of my days with him and come back home in the evening."

She added, "You young women are so fortunate to have a world built like this for you."

Shila Ahsan, 35, a doctor at BIRDEM hospital, commutes daily from Mirpur to Kazi Nazrul Islam Avenue. "Not only do I have peace of mind knowing I'll reach work on time, but the journey feels so homely that I even start working on my paperwork in the women's compartment," she said.

As she spoke, a few papers slipped from her file, and another commuter picked them up from the metro floor and handed them back. Shila glanced at me, gestured towards the scene, and shrugged as if to say, "See? It speaks for itself."

Bina Rani Das, 21, a garment worker in the Tejgaon area, was on her way to visit her sister in Kalshi. A bit hesitant to speak, she shared, "My sister is seven months pregnant now. We moved to Dhaka from Sylhet last year."

"Dhaka frightens me," she said, looking a little embarrassed. "I even live right next to my workplace so I don't have to travel. The rudeness of people scares me, and as a garment worker, bus drivers and helpers don't feel the need to treat me with respect."

"The women's compartment on the metro is the only way I can travel and visit my sister," Bina said.

These are just some of the stories from life in the metro, which is slowly rewriting the narrative of Dhaka's public transportation pandemonium.

One needs places to call their own to be the person they want to be. Dhaka constantly challenges that. So, no wonder a female compartment, which on paper is such a basic thing, makes women appreciate it so much, now more than ever.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments