Shinduria: A hidden haven of biodiversity near Dhaka

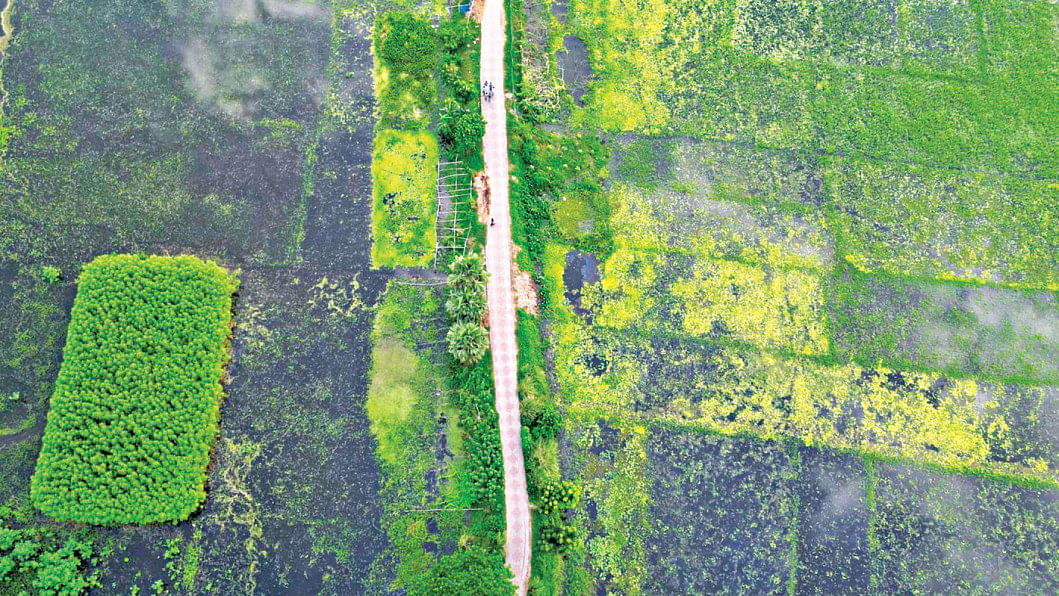

Just 35 kilometres from the noise and fumes of Dhaka, and a mere five kilometres from Jahangirnagar University, lies a quiet village most city-dwellers have never heard of: Shinduria.

Cradled along the banks of the Dhaleshwari River and linked to the Bongshi River in the Gerua area of Savar's Pathalia Union, Shinduria is more than just a scenic village -- it is a thriving ecosystem shaped by water, tradition, and time.

It is a living, breathing ecosystem -- nourished by seasonal floods, sustained by traditional practices, and home to an extraordinary range of wildlife. Despite its proximity to one of Dhaka's most polluted rivers, the floodplains here remain surprisingly vibrant.

"Because Shinduria is relatively remote and free from heavy industry, the river water here remains clear,"

A Floodplain Full of Life

Each monsoon, Shinduria and neighbouring Mirertek are submerged by nutrient-rich floodwaters that rejuvenate the land. These waters leave behind fertile silt and organic matter, boosting the productivity of native grasses, crops, and wetlands.

"Because Shinduria is relatively remote and free from heavy industry, the river water here remains clear," said Prof Amir Hossain Bhuiyan of Jahangirnagar University's Environmental Science Department. "But as the Dhaleshwari flows downstream towards Savar and Dhaka, it turns dark and toxic due to industrial waste, sewage, and urban runoff."

This upstream clarity makes Shinduria's wetlands a seasonal paradise.

A Sanctuary for Birds, Mammals, and Reptiles

From the rustling grasslands to the silent coconut groves, Shinduria has become a haven for birds and other wildlife. Field observations and research surveys have recorded dozens of bird species, including the Siberian Rubythroat, Siberian Stonechat, Watercock, Baya Weaver, Black-breasted Weaver, Chestnut-headed Munia, Tricoloured Munia, Indian Silverbill, Common Myna, Black Drongo, Spotted Dove, Little Cormorant, Little Egret, Lesser Whistling Duck, White-throated Kingfisher, Bronze-winged Jacana, and Pheasant-tailed Jacana. These birds feed, nest, and breed here, attracted by the abundance of food and safe habitat.

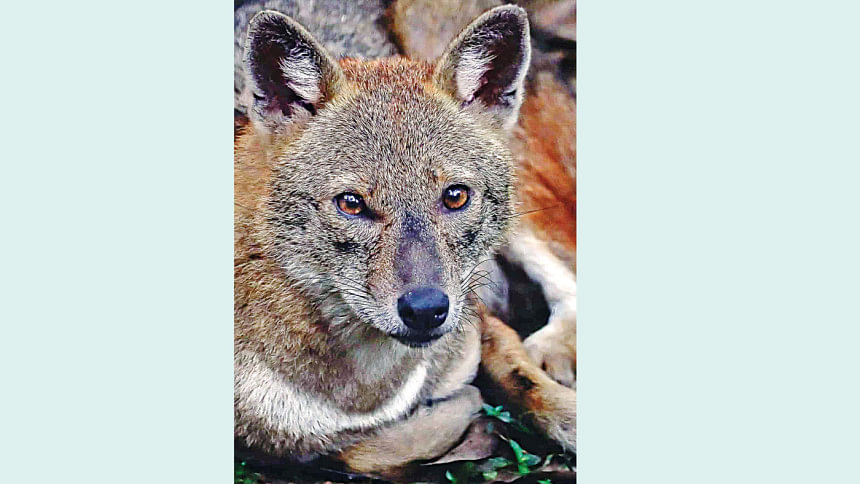

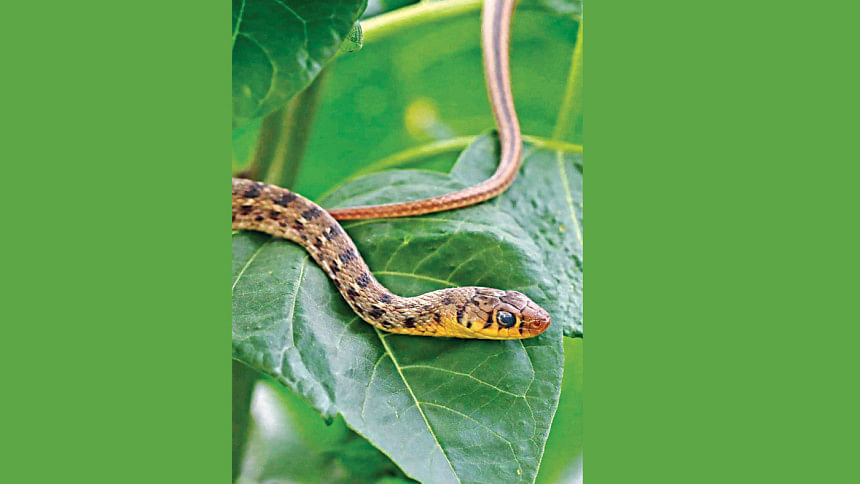

Auritro Sattar, a conservationist and Environmental Sciences student at Jahangirnagar University, documented 12 mammal species in the area, including the Large Indian Civet, Small Indian Civet, Common Palm Civet, Golden Jackal, Jungle Cat, Fishing Cat, Greater Bandicoot Rat, and Common House Rat. He also recorded 15 reptile species, notably the Monocled Cobra, Spectacled Cobra, Banded Krait, Lesser Black Krait, Indo-Chinese Rat Snake, Painted Keelback, Checkered Keelback, and Smooth-scaled Water Snake.

"The biodiversity here is deeply rooted in the community's traditional lifestyle," Auritro explained. "Even household waste contributes organic nutrients to the ecosystem."

One of the village's most fascinating features is its coconut tree groves, planted decades ago by villagers. These trees have evolved into natural nesting sites for birds like the Munias and Weavers.

"In a 400-metre stretch, we found over 300 nests," Auritro said. "Some trees had as many as 50 nests."

These groves are now quietly attracting birdwatchers, amateur photographers, and curious travellers.

"I was amazed," said Sharmin Rahman, a visitor from Dhaka. "The calls of birds, the soft wind, and the shimmering water -- it feels like another world."

A Fragile Future

But Shinduria's peaceful rhythm is being disrupted.

The majority of Shinduria's residents are engaged in agriculture and small-scale businesses, which include grocery shops, vegetable stalls, and fish trading. In terms of agriculture, locals primarily cultivate paddy, seasonal vegetables, and mustard.

Additionally, a portion of the population is employed in various positions at Jahangirnagar University, while some work in the garment industry.

However, in recent years, the rapid expansion of restaurants, poultry farms, and infrastructure has led to the filling of floodplains and wetlands. These developments are discharging plastic, chemicals, oils, metal scraps, restaurant and construction waste, causing serious damage to both soil and water ecosystems.

"Because of plastic deposition, the soil fertility in these floodplains is decreasing. Chemicals are not dispersing as they should, and the oxygen in the water is getting blocked by surface oil layers," warned Prof Bhuiyan.

"Coconut trees are also dying, possibly due to increased radiation and environmental stress. If they disappear, the birds will follow -- leading to a chain reaction of ecological imbalance."

He continued, "Such changes will severely impact the biodiversity and the delicate ecosystem that has developed here over generations. Even Jahangirnagar University's wetlands are at risk. Since these ecosystems are hydrologically connected, filling in Shinduria's floodplains could eventually cause waterlogging on the university campus itself."

Tourism, too, is becoming a double-edged sword. The increased foot traffic, litter, and noise are already disturbing wildlife.

Over two years, conservationist Auritro Sattar observed the importance of these types of annual floodplains in Shinduria and Mirertek. They trap sediment and dilute pollutants, breaking them into less harmful forms while supporting biodiversity. During dry seasons, soil cracks enhance oxygen flow, limiting methane and carbon monoxide production. These floodplains also foster fertile grasslands that sustain insects and granivorous birds, linking aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems even near polluted areas like Dhamrai. However, this balance is under threat from rapid development -- plastic, paper and food waste from restaurants, motorbike emissions, poultry farms, overfishing, boat activity, and landfilling — putting pressure on the ecosystem's ability to maintain environmental stability and pollution thresholds.

Hope in Local Action -- But Is It Enough?

Still, there's a glimmer of hope. Local residents and young conservationists are stepping up.

Auritro and his team have started awareness campaigns, going door to door to educate villagers and business owners.

"I cut two of my coconut trees when I rebuilt my house," said Saiful Islam, a 65-year-old resident. "Had I known they were important for birds, I wouldn't have."

His family planted those trees 35 years ago. For over 16 years, hundreds of Baya Weavers have returned to nest there, especially during the months of Falgun, Bhadra, and Ashar.

Saiful also recalled that his was one of only six households in the area decades ago. Now, new settlements -- often unplanned -- have sprung up on the floodplains, contributing to habitat destruction.

"The natural beauty of Shinduria brings joy to all of us. We grew up here -- this open field, the riverside, the environment -- you won't find such beauty anywhere else in Savar. Earlier, not many people used to come here, but with the improvement of roads, more and more visitors are arriving. Shops are also being set up. In a way, it feels good, since the place used to be quite isolated. But sometimes, the large crowds become uncomfortable for us, and the environment is gradually changing," said Sheikh Abdul Kader, 24, a resident of Sindhuria.

Some business owners are also seeing the bigger picture.

"People come here for the beauty," said Jasim, who runs a local restaurant. "If we destroy it, our business dies too. We want to help -- but we need proper guidance."

While these grassroots efforts are encouraging, experts agree: they're not enough.

Institutional backing, stricter environmental regulations, and community-based conservation models are urgently needed. Without them, the slow erosion of Shinduria's ecosystem could become irreversible, they said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments