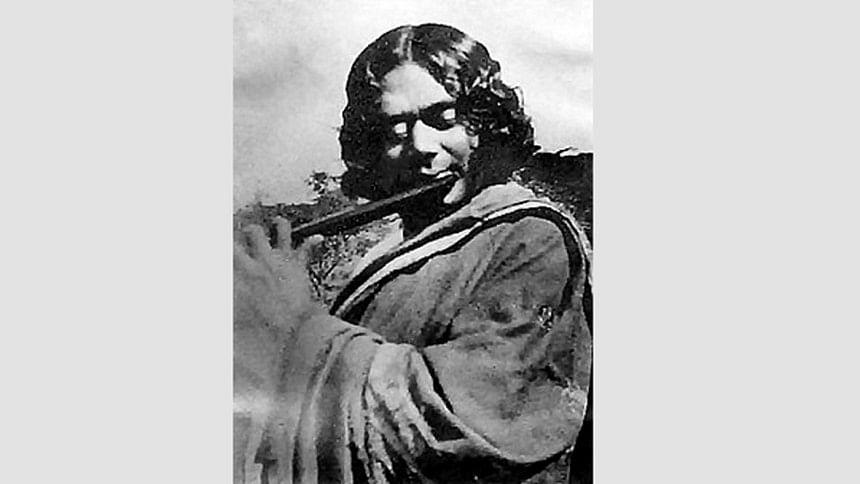

Where Nazrul’s flute still echoes

In the quiet corners of Trishal, Mymensingh, the spirit of Kazi Nazrul Islam lingers -- not just in memory, but in rhythm of rustling leaves, in the dust-laden paths of Namapara and Kazir Shimla, and in the whispers of an old banyan tree beneath which a young boy once played his flute.

Here, in this stretch of rural Bengal, Nazrul is not a distant national icon. He is still a neighbour, a schoolboy, a dreamer whose footsteps echo in the hearts of the people.

It was June 1913. A 14-year-old boy from Churulia village in Burdwan, West Bengal, arrived at Kazir Shimla in Trishal. Taken in by police sub-inspector Kazi Rafizullah, the boy had no idea that his name -- Kazi Nazrul Islam -- would one day become synonymous with rebellion, resilience, and revolutionary verse in Bengal and beyond.

"The memories of Nazrul are still alive among us. When we see the banyan tree on the Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University (JKKNIU) campus, we feel as if the boy is still there, playing his mesmerising flute," said Abdur Rahman, a resident of Namapara village, his eyes fixed on the leafy silhouette.

Though Nazrul stayed in Trishal for only about a year, his impact on the area has outlasted lifetimes. The local folklore around his time here has become part of the cultural identity of the region.

According to Rashedul Anam, a Nazrul researcher and additional director of the Institute of Nazrul Studies at JKKNIU, the poet was admitted to class VI at Darirampur High School, now known as Nazrul Academy, where Bipin Chandra Chakraborty served as headteacher.

Back then, the journey from Kazir Shimla to the school was long and unforgiving -- nearly six miles without any proper roads. Recognising the hardship, Nazrul moved to Namapara, nearer to his school, and stayed at the home of Bechutia Bepari.

"He would often stop under the banyan tree on his way to class and play his flute," said Anam. "That sound has become part of our collective imagination."

Nazrul's presence left an indelible impression on the villagers. He was widely known for his engaging "Punthi" recitations (a traditional form of poetic storytelling) and his remarkable command of the flute. His music would often drift through the village, making him a beloved figure even as a teenager.

In his book Nazrul Jiboner Trishal Addhay, Anam recounts how Nazrul's English teacher, Mohim Chandra Khasnabish, remembered him as "a quiet and absent-minded boy" -- a stark contrast to the charisma he displayed on stage during the school's cultural events. There, Nazrul would dazzle with dramatic recitations of Rabindranath Tagore's "Dui Bigha Jomi" and "Puratan Bhrittya," earning awards for both.

He was not simply performing -- he was embodying the voice of resistance and empathy, long before he found fame. According to local accounts, the boy had an unmatched ability to convey emotion.

"Even at that young age, he had something magnetic about him," said Tapu Devnath, a fine arts graduate who has studied Nazrul's influence on the visual arts. "The banyan tree where he played takes us more than a hundred years back, while it stands as a living monument."

Then, just as suddenly as he had arrived, Nazrul announced he was leaving. After finishing his class VII annual exams, he informed Saforjaan Banu, daughter-in-law of Bechutia Bepari, that he planned to return to West Bengal. She gave him some coins to help him with his journey.

Before leaving, he wrote a letter to his headteacher, expressing gratitude and his plans. When the letter was read aloud in class, the entire school fell silent. Emotion swept through the students and teachers alike. Several set out to find him, but Nazrul had already left. The letter, unfortunately, was never preserved.

To many, this departure marked only the beginning of Nazrul's transformative journey, but to the people of Trishal, it was the beginning of an eternal bond. "He may have left Trishal physically, but he never really left," said Nagarbashi Barman, head of the Fine Arts Department at JKKNIU. "His soul is in our soil."

That legacy would later take institutional form. In 2005, the foundation stone for the Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University was laid in Namapara, bringing the poet back, symbolically, to where his intellectual and emotional blossoming first began. The university officially began academic activities on June 3, 2007, with three departments under the Faculty of Arts -- Bangla Language and Literature, English Language and Literature, and Music -- and one under the Faculty of Science and Engineering.

Today, JKKNIU is the only public university named after the national poet. Located 22 kilometres from Mymensingh city, the institution now has 25 departments and 10,809 students. Its curriculum, which places strong emphasis on liberal and performing arts, reflects the multifaceted legacy of Nazrul. Departments like Music, Theatre and Performance Studies, Film and Media, and Folklore are testament to that.

At the heart of the university lies the Institute of Nazrul Studies, which promotes research, publications, and performances dedicated to the poet's life and work.

Yet, there remains room to grow. "Departments like Dance and Musical Instruments have yet to be established," said Prof Dr Sushanta Kumar Sarkar, head of the Music Department. "If these are introduced, this university can become our own Shantiniketan."

The university also commemorates Nazrul's family by offering scholarships and stipends named after his wife Promila Nazrul, sons Bulbul, Kazi Sabyasachi, Kazi Aniruddha, and daughter-in-law Uma Kazi.

Outside the university gates, efforts to preserve Nazrul's memory are visible in the two Nazrul Smriti Kendras at Kazir Shimla and Namapara. Established in 2003 by the Department of Archaeology, the centres contain a modest but significant collection of memorabilia: handwritten manuscripts in Bengali, English, Hindi, and Urdu; rare photographs; a simple cot; and original gramophone records released by His Masters Voice.

However, the centres have not been updated in over two decades. As a result, the number of visitors has steadily declined. "It's monotonous to see the same items year after year," said Kazi Nayeem Ahmed, a recent visitor.

According to Kazi Abu Sayem, a local youth, only 15 to 20 people visit daily.

The accompanying libraries also show signs of neglect.

"Books by Nazrul are available, but we need more diversity -- other authors, perspectives, new scholarship," said Sahana Akter, a local college student.

Akhtaruzzaman Mondol, assistant director (in charge) of the centres, acknowledged the issue. "The National Museum and the Nazrul Institute in Dhaka have rich collections. If those were shared with us, we could improve the experience for visitors here."

Still, the centres serve as cultural anchors, hosting music courses and commemorating Nazrul's birth and death anniversaries, alongside other national days. These events rekindle public interest and keep Nazrul relevant for new generations.

The poet's birth anniversary today, for instance, is marked with three-day celebrations jointly organised by the Mymensingh District Administration, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, and JKKNIU.

Seminars, cultural programmes, book fairs, a Nazrul Mela, and photo exhibitions create a vibrant tribute to the rebel poet. Darirampur and the JKKNIU campus come alive with music, verse, and memories.

The people of Kazir Shimla and Namapara still feel an intense pride in their connection with Nazrul. "We feel honoured that Nazrul first came to Bangladesh through our Kazir Shimla," said Kazi Abul Kashem, grandson of Rafizullah.

"His presence has glorified us," echoed Abu Yusuf Dulal, a fifth-generation descendant of Bechutia Bepari.

Both families have called on the government to take stronger measures to preserve the memories and physical traces of the poet's youth.

"There is a sense that Nazrul's flute never truly fell silent. Even now, when the wind brushes through the leaves of the banyan tree, some say they can hear a faint melody -- a reminder that the boy who once wandered through these fields with a head full of verses and a heart full of dreams never truly left," said Dulal.

Here in Trishal, Kazi Nazrul Islam lives on -- in the landscape, in the people, and in the lingering notes of a flute that still echoes through time.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments