Where grows the spirit of liberation?

In 1971 the Pakistani military shot dead sixty-seven people from our village in just one day. There were children among those sixty-seven; there were youths, senior citizens and women among them. Fifteen other people from the village lost their lives during the war. These fifteen were not killed directly at the hands of the Pakistani military - they were murdered by the Razakars and the Al Badrs.

I came to learn of two of these murders. One night, a father and his son were returning from a market that was quiet a distance from their home. They had been walking the four mile road together. When they had covered those four long miles, right up to the point where they just had to step off from the road to get to their house, both were shot dead. The villagers had been able to identify the killer. The man who killed the father and the son was a family member – a nephew to one of the dead. There was a long standing legal dispute between the uncle and his nephew regarding land. The nephew had joined the Razakars out of hatred for his uncle and his cousin, to gain ownership of the land. When a country is at a moment of crucial import, the established relations among the villagers polarises in favour or against the issue. Incidents can be found where the prevailing mentality was– if my enemy is supporting the Liberation War, then, I must oppose it.

I was out of the country during the entirety of the war. After the war ended and I returned home, I wanted to keep a record of the barbarities that were committed during those nine months. I learned that the majority of the people who died were killed in Palpara, which was located at the South-Eastern edges of our village. Khetromohon, who I had studied with in school, was from Palpara. Khetromohon had the rare talent of making people laugh with his stories. Even the most trivial would turn into hilarity in his words and we would be bent double with laughter. I would spend nights at his house. At times, he would come over to ours and stay the night. A friendship had grown between our families centring ours. I visited Palpara the day after I returned. My wish was to keep a record – who had died, whose houses have torched and vandalised and so on.

Khetromohom was not home when I reached the place. I learned from the locals of how his wife had taken her own life by throwing herself into the fire. I present the story here in brief – The Pakistani military had set fire to the house and were going after the young girls. Seeing the situation unfold in front of her eyes, Khetromohon's wife had jumped into the fire and was burnt alive.

I had witnessed many deaths during the war. There was a time when the line between life and death had blurred within my mind. But the story of how my friend's wife had killed herself left me stupefied. When Khetro was to get married to this woman, I was to be part of the groom's entourage. I forget why I could not go but Khetro was angry at me for my failure. I would visit Khetro at least once whenever I visited my village. The sound of voice would be enough and his wife would put the kettle on the fire. I had many a times shared my happiness and sorrow with her.

I have already mentioned that Khetro was not home when I arrived at Palpara. He returned within half an hour, and seeing me, the first words to escape his lips were – did you drink tea yet? No mention of his wife's death, his torched home – he was trying to bring back the humour and banter of our past. Khetro's attempt to be cheerful brought me close to tears.

Shadhon was another friend – Shadhonkumar Dhor. A thin-framed spectacle used to perch on his face since childhood. The Pakistani military had killed him. Shadhon used to live at his uncle Shibchoron Babu's hosue. Shibchoron's baby was murdered too. I asked those of the family who had survived if they could show me those thin-rimmed spectacles - if they still had it, it would at least give me some consolation. I was told the military had taken away those glasses along with my friend. He had never returned.

Starting 1972, every time I visited the village, I repeatedly tried to convince the villagers of one thing. From the members and chairmen to the village leaders and elders – I tried to convince them of one single thing. Almost a hundred people from our village had been killed at the hands of the Pakistani military, the Razakar and the Al Badr. The Chittagong-Cox's Bazaar road runs through our village – I proposed that a memorial bearing the names of the hundred who had died be constructed at the entrance of our village, beside this road.

I also proposed a line to be written in their remembrance – “Traveller. The village that you cross – a child of this village had given his life for the freedom of this country.” I have been suggesting this since 1972. At first the people had tried to listen attentively to what I had to say. After three-four years had passed and I was still bringing up the issue – people began to think I was embarrassing them unnecessarily. I suspect that if I dare to bring up the issue at present, I would be looked upon as a madman.

My work has taken me frequently to eight or ten districts from the North to the South of Bengal and in between. Wherever I went, I asked people of the stories of what happened there during the war. People from many villages responded saying, “The Punjabis did not come to village at all.” Many other villages spoke of the arrival of the Punjabis, the torching of houses and the killings. I asked them if they knew the names and identities of those who had died. With enthusiasm they would answer, “Why would we not!” They would talk of so-and-so's son grandchild or brother.

I used to then ask, “Why do you not write the names of those who died in the war on the sides of the road? When travellers will pass by and read the names, a respect for your village will take root at their hearts.” The villagers would stare blankly at my face. It was as if they were completely incapable of understanding the significance of what I had to say. Nowhere I went did I see the names of the martyrs written down and remembered with care and respect. To do something like this, no great initiative would have been required. A little love for the country and a little respect for those who had lost their lives in the war would have been enough.

Every December in Dhaka my ears hurt from the cackle of a thousand speeches made about the spirit of our Liberation War. Those plump ladies and gentlemen, in their neat-elegant clothes, their voices breaking from the emotion, who pontificate on the spirit of the war – do they know where grows the spirit of our war of liberation?

This article was first published in Khoborer Kagoz, Year 19, Issue 50 on December 12, 2000.

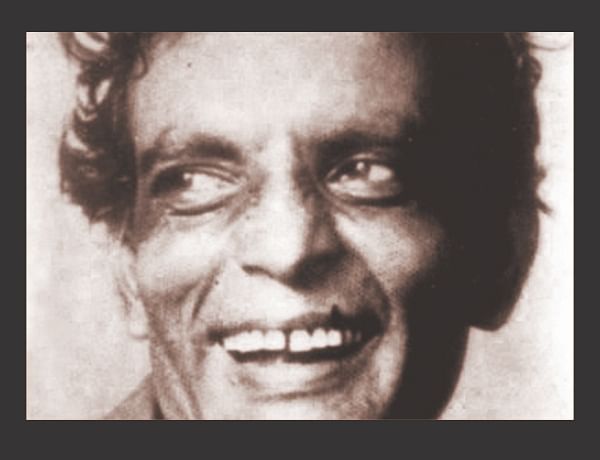

Ahmed Sofa was a famous poet, novelist, author, translator and activist. He is one of the great intellectuals in the post-Liberation Bangladesh.

Translated by Moyukh Mahtab. He is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments