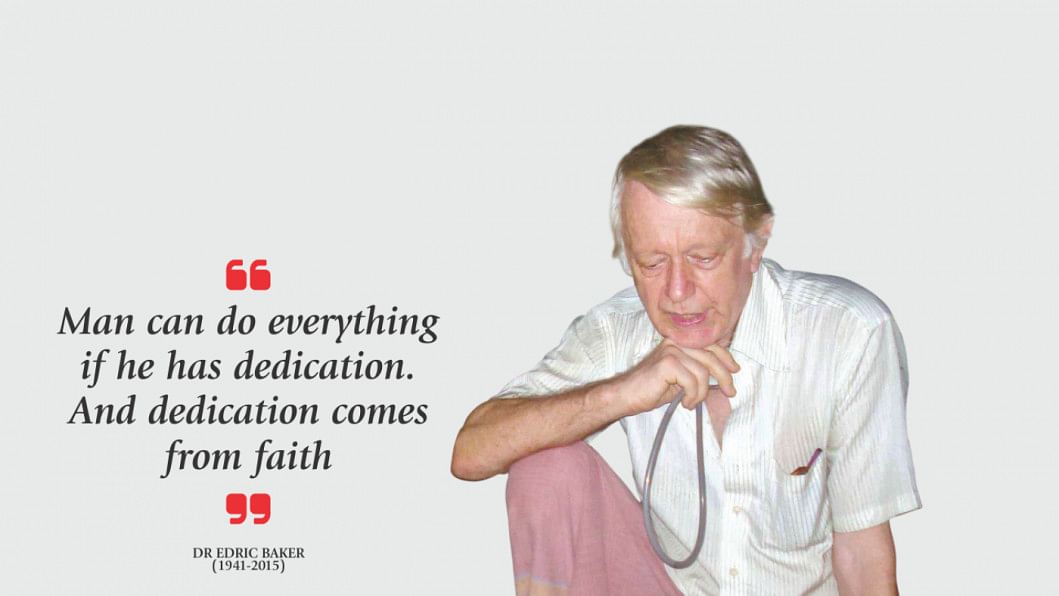

The Good Doctor

“My days are numbered now," Edric Sargission Baker told his associates soon after he was diagnosed with pulmonary artery hypertension in 2013.

An accomplished doctor himself, he then described the symptoms that would indicate his time had come.

"When you see these symptoms, do not put me on mechanical ventilation or any other life support," Dr Baker said to the shock of his associates.

"What! Why would you say that?" asked one of them, failing to make sense of Baker's apparently bizarre instruction.

The doctor smiled. "It's because I don't want to receive any treatment that I could not give to my patients."

|

Profile Personal Education Work Experience In Bangladesh Award |

An uncomfortable silence fell on the veranda of Kailakuri Healthcare Centre that the New Zealander had established in Tangail over three decades ago.

"I want a Christian funeral for myself," Baker broke the silence.

"And bury me in the backyard of the house," he said, pointing to his humble mud house.

Pijon Nongmin, manager of the Kailakuri Healthcare Project, was narrating this experience two weeks after the death of Dr Baker on September 1.

"And have done exactly what he had wished. We didn't put him on life support during his last days and laid him to rest behind his hut, following proper rituals," he said.

Baker was born to John Baker, a statistician, and Betty Baker, a teacher, at Wellington in New Zealand on August 12, 1941.

After obtaining his MBBS degree from Otago Medical College in Dunedin in 1965, he joined a government medical team and served in war-ravaged Vietnam twice till 1975. He then went to Zambia and Papua New Guinea to serve the poor there.

In the meantime, Baker completed advanced courses in Australia and England on maternal and child health.

It was between his two Vietnam tours that he came to know about the sufferings of the Bangladeshis.

Stories of the Bangalees being tortured by the Pakistani forces during the 1971 Liberation War perhaps grew in him sympathy for the people of Bangladesh, said Pijon, who worked with Dr Baker for over five years.

In 1979, the doctor first came to Bangladesh and joined a Christian mission hospital in Meherpur. Two years later, he moved to Kumudini Hospital in Tangail. After working there for eight months, he joined a clinic run by the Church of Bangladesh at Thanarbaid of Madhupur in 1983.

But Baker soon realised that he needed to learn Bangla if he really wanted to understand his patients, many of whom were indigenous people. And within a year, he learned to communicate in Bangla.

Immediately after joining Jalchhatra Christian Mission Clinic in Madhupur, he opened a small healthcare centre at Kailakuri in 1983 to deal with the quickly growing number of patients.

Then in 1996, Daktar Bhai, as he was lovingly called by his patients, turned this small chamber into Kailakuri Healthcare Centre.

"With the kind of expertise he had, Daktar Bhai could have made a career in any developed country and lived a life of luxury. But instead, he chose Bangladesh and a simple life," Pijon told The Daily Star.

"There was no furniture inside his room. Not even a cot. He would sleep on the floor," he added.

During an interview with The Daily Star in 2011, Baker was asked what prompted him to come thousands of miles away from home and work inside a reserved forest area, about 170 kilometres from the capital.

"It's the local people here. They are really very good," he had replied.

“In my childhood, I promised to myself that I would help the helpless. And I am simply living up to that promise."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments