The Circus Story

Shahin is no Priyanath Bose. Nor does his outfit come anywhere near the Great Bengal Circus. Yet he is carrying forward the legacy of circus in Bengal through thick and thin.

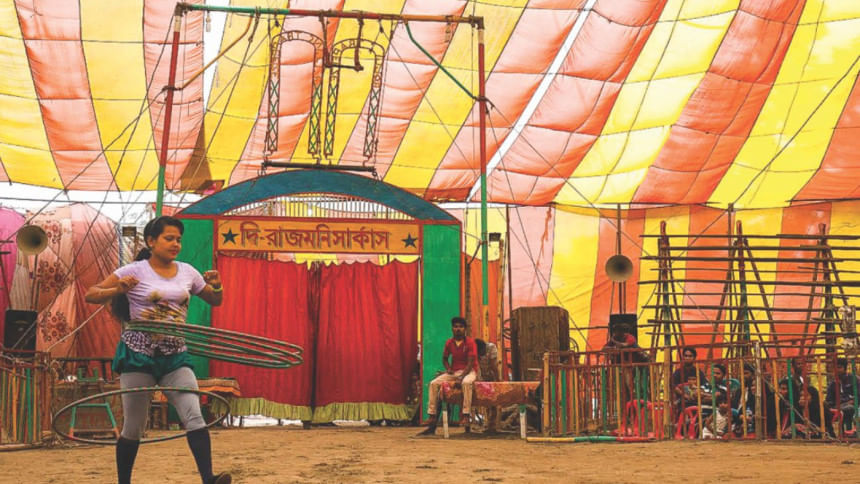

Wearing a lungi and a striped T-shirt, Shahin saunters around the big marquee of his The Rajmoni Circus. A three-day stubble bristling on his face.

Outside, a big canvas panel announces the marvels one would get to see in his show. Two happy elephants with raised trunks. Two tigers roar on the wings. Some jazzy snapshots of performance.

Inside, it clearly shows luck was giving out with Shahin. Under the huge canopy of the marquee, the spectators sit on rickety wooden stairs set on the edges. The cheap audience just squat for Tk 70 on polythene sheet spread on the sandy ground and gawk at the things happening in the middle.

A malnourished man in a red dress tries to balance himself on a plank on a roller perched on a high platform. The plank dangerous rolls from side to side. And the man just manages to stay on it.

Then he shows some silly versions of acrobatics that look more like yoga positions. The audience greets him with applauses.

After him comes a girl in a typical Bengal circus outfit -- tights with a baggy upper part, lots of creases make it look like a pumpkin. The heavy makeup makes her face floating from the rest of her body.

She stands on the plank and balances a ball on her nose. Claps again.

Shahin takes us to the backyard outside the tent.

“Here are my animals. The bears and the tiger.”

“Tiger? Really?”

Two big cages house two big Asian black bears. They look fat and bored.

“They are old,” Shahin says. “One is 30 years old, the other 20 years. I got them young from India.”

“And the tiger? Where is it?”

He takes me to a smaller cage. To my disappointment I find a fishing cat resting there. Its emaciated body panting with the effort of breathing. Half of its tail missing, probably during its capture with a trap.

“That's your tiger? How do you pass it as one?”

“It is the tiger. Just wait and see,” Shahin grins.

That reminded me of the Great Bengal Circus and its founder Priyanath Bose.

In 1887 Bose set up the first Indian circus company the Great Bengal Circus in Kolkata.

But before he could finally do it, Priyanath trained as a gymnast and wanted to set up his Akhra to teach gymnastics to others. His father thought otherwise. He believed Priyanath had painting talent and so wanted him to be an artist.

In the end the son won and he went on to become a gymnastics trainer and then eventually set up his own Akhra. He had very strict rules for the students. They could not smoke and sniff tobacco. They had to get engaged in voluntary cleanliness campaigns in the villages.

In 1885, he performed before the then viceroy of India Lord Dufferin who was so impressed by his feat that he called him a professor.

Kolkata was then a thriving metropolis, India's jewel in the crown. Cleaners would dust the roads and open the hydrants to wash them glisteningly clean even before the dawn broke. Vistawallahs would carry water in leather bags to supply houses while the pressurised paraffin lamps would burn bright by the streets.

It was a city of pomp and desire. The Jamindars and Shahibs would ride to parties on Fitton cars.

Great circus companies from around the world would come to Kolkata, Calcutta then. Priyanath was a regular visitor to the shows and from there he drew the idea of setting up his own all-Bengali team

He took meticulous notes of the costumes the circus artists wore. He would bribe the circus workers and sneak into the backroom to make sketches of the equipment.

His father would not pay a single dime for his venture and so Priyanath borrowed some money from the women of his family.

He cobbled up a rag-tag team but did not have enough money to buy a marquee or even a tent. Despite that he left Kolkata on a tour of Midnapore, Jharpore and Bankura. He came back to Kolkata a little richer with his shows all successful.

It was time to go big. So he started buying equipment, animals and also recruited more talented performers. Finally in 1887 he launched his Professor Bose's Great Bengal Circus.

Unlike Bose, Shahin inherited his circus from his father whose Bulbul Circus was quite famous for its interesting shows. But instead of running the old one, he set up his own venture Rajmoni Circus with a 100-strong team.

As always, it is difficult find build a circus team.

“You don't get any readymade talent. What I do is I go around the country and hunt for talents,” Shahin says. “We prefer kids for acrobatic training. Dwarfs for clowns. Some village magicians.”

Business is harsh. For an outfit of 100 men, women and children, the everyday cost of running the show runs up to Tk 50,000.

“Sometimes we make losses too. Sometimes we do not get permission to set up our camp for security reasons. Those idle days are difficult because the cost clock never stops ticking.”

Shahin runs his circus for 11 months a year. The Ramadan month is an off-show season when the team members get leave. They pack and go home.

Days the show cannot be held for some reasons like say Hartal or delay in getting permission from the local administration, the cost keeps ticking on. “I have to feed them two square meals no matter whether the show goes on or not,” says Sahin.

He carries the conversation to the back of the marquee where his animals stay, the bears, the “tiger” and the monkeys. A goat is tied so tightly that it seems he is trying to commit suicide by hanging. The goat walks the rope.

On close notice, we find one of the bear's ear torn at the top. The other's nose is half torn. Must have been the gifts from rigorous and merciless trainings they undergo. The bears show no interest in us and just keep lying.

Later, towards the end of a show, the trainer, a nondescript man on the wrong side of the 50, comes and lifts the door to the cages. The younger bear, smaller in size, lazily lifts itself up and steps out. Circus team members line up to the marquee to make a path for the bear and the trainer cracks his whim. The bear lazily run inside the ring.

The trainer puts up a mock fight with the reluctant bear. The man and the beast wrestle on the sandy ground. The beast is defeated easily. Then it is made to stand on its hind legs and walk like a man and dance. The audience claps. The bear is brought back to its cage.

The monkeys constantly fight and screech in the cage, probably out of hunger.

And hunger stalks the animals all the time. Their staple food is milk and rice. Even the fishing cat and the bears are forced to eat that. It is a miracle that the fishing cat, a carnivore, is still surviving on that diet. It has though turned into a paler shade of what it was with its bones sticking out.

The elephant has been sent to the villages to seek out its own food of banana trees.

Food is important for all in the circus for the grueling work they do. Beside a row of tin shanties that house the team, a man is dishing out rich and red hot beef curry to the long queue of performers who wait patiently with plastic plates in hand for their turn.

We meet Rekha there, the star performer of the circus. A 16-year-old girl clad in bright yellow circus dress. She looks a little plump from a carbohydrate rich diet.

“I joined the circus when I was a little kid of eight,” she coyly says. She is not much of a talker.

Her father is a rickshaw-puller of Netrokona. Poverty stalked them every day.

Rajmoni Circus had laid out its tent on a field in Netrokona and was there for a month. One day, Rekha's father approached Shahin and offered his daughter to the circus.

Shahin readily accepted her. This is, after all, how he collects his performers.

“We coached her four to five hours every day. At first she was too scared of the acrobatic tricks. She would refuse to walk on wire. But soon she caught up and became my star performer. I pay her 1,100 taka for each day of show and food,” Shahin says with a whiff of proud.

Eleven hundred taka is a lot of money for Rekha. It does not matter she has to perform from the first show at nine until the last show at 12 at night. That money goes a long way to run the family of her ailing father.

As we are talking Rekha's call for show comes. She slips inside the marquee. She stands still in the middle of the huge canopy, looking forlorn and yet ready for the show. She takes a deep breath and then springs into agility.

Rekha jumps up and gabs a rope hanging from the ceiling. She swings wildly and takes a long curvy loop to land on a wire. Someone passes a long stick.

She holds it, takes a little time to gain balance and then starts walking the wire.

The two little clowns with their faces dyed in all colors are looking up at her and try to be funny, wishing her a hard fall from the sky.

Shahin, our own Priyanath stands at a distance, looking proudly at his star performer.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments